Back to Basics: Decoding Hepatic Encephalopathy

Learning objectives

In this Back to Basics series, the learner will be able to:

- Explain the role of ammonia in physiological changes in hepatic encephalopathy (HE)

- Formulate a diagnostic approach for HE

- Understand key management strategies

What is hepatic encephalopathy and how does it occur?

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is brain dysfunction resulting from liver impairment or portosystemic shunting, presenting as a spectrum of neurological and psychiatric manifestations.

Ammonia is formed by bacteria as a breakdown product in the gut, and metabolized by the liver. In patients with advanced liver disease, ammonia negatively affects astrocytes, alters pH levels, membrane potentials and electrolyte balances. The impaired gut-liver-brain axis in cirrhosis, characterized by an imbalance between beneficial and pathogenic gut microbiota, leads to increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation. This impairment is associated with neurocognitive dysfunction in patients with advanced liver disease.

What are clinical manifestations of HE?

Overt HE, characterized by varying levels of disorientation and alertness, heralds a critical landmark in the natural history of a patient with cirrhosis, as median survival plummets to 2 years after diagnosis. Up to 40% of patients with cirrhosis will develop overt HE in their lifetime. An even higher proportion has minimal or covert HE which involves subclinical neurocognitive defects only identified on psychometric testing. Cognitive dysfunction linked to cirrhosis not only leads to higher health care resource use than other stigmata of liver disease, but also increases emotional and socioeconomic burden on patients and caregivers.

HE produces an array of nonspecific clinical manifestations. In early stages, subtle changes in attention, working memory, psychomotor speed or visuospatial abilities are experienced.

Asterixis is often observed in early to middle stages of HE. Derived from Greek (‘a’=not, ‘stērixis’=fixed position), it is not a tremor but rather a negative myoclonus, with loss of postural tone. Asterixis is commonly elicited by hyperextension of the wrists, with fingers wide apart (Youtube video linked here). Asterixis can also be seen in patients experiencing uremia and hypercarbia.

As HE progresses, personality changes, alterations in consciousness, motor activities and sleep disturbances develop, with some patients progressing to coma and death in severe cases.

How is HE classified?

The most common way to classify HE is by severity, using the West Haven Criteria (more on our LFN Quick Tips sheet linked here). It can be reassessed periodically with changes in clinical status.

What are triggers for HE?

- Infections are the most frequent precipitants. Diagnostic paracentesis is crucial in evaluating for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A clinical evaluation for pneumonia, urinary tract infection, gastroenteritis, and other sources of sepsis along with culture data is part of a comprehensive infectious work up. Often, empiric antibiotics are started even before culture data is available due to the risk of clinical decline.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding is a common precipitant, and efforts must be undertaken to identify the source, treat, and rapidly clear blood from the GI tract, as degraded blood products produce urea which is then absorbed in the intestine and can lead to increased ammonia.

- Dehydration in patients with cirrhosis can lead to HE. It is often multifactorial – related to diuretic or laxative overuse or large volume (>4L) paracentesis. Holding diuretics with supportive therapies to maintain volume status may be necessary.

- Electrolyte imbalance can also provoke HE. Hyponatremia should be corrected at a physiologically-safe pace, and hypokalemia can lead to an increased renal ammonia production and should be promptly replaced.

- Certain drugs and toxins are linked to the likelihood of HE. For instance, opioids functionally increase ammonia absorption due to slowed intestinal motility. Benzodiazepines can amplify the brain-depressing effects of ammonia. Ongoing alcohol use can impair the liver’s ability to detoxify ammonia.

- Shunts, whether naturally formed or surgical, can worsen HE by diverting blood away from the liver, thus reducing the amount of blood detoxified by the liver. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) can increase the risk of HE – see a related LFN post, linked here, to learn all about this! Reduction of shunt diameters can help reverse HE. Another type of shunt called splenorenal shunt, which connects the splenic vein and renal vein, can be formed spontaneously due to portal hypertension and carries the risk of worsening HE.

- Constipation leads to increased reabsorption of toxic metabolites from the GI tract, and is associated with an increased risk of precipitating HE, and must be treated (more on this in the “management” section). It is important to remember that constipation is a diagnosis of exclusion after the more life-threatening differential diagnosis mentioned before has been evaluated.

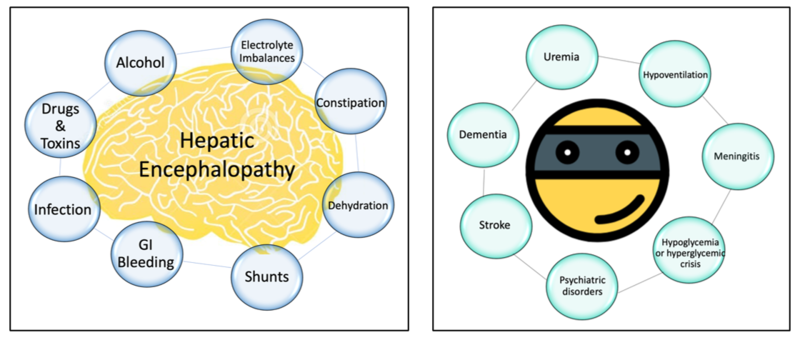

- Beware of mimickers! Similar to any patient presenting with acute mental status changes, intracranial haemorrhage and stroke, glucose abnormalities, neurological infections, intracranial lesions, psychiatric disorders, seizure activity or toxic encephalopathy from other causes should be considered (Figure 1). Necessary laboratory and radiological assessment should be targeted to the clinical presentation that fits.

Figure 1: Triggers (left) and mimickers (right) to consider when evaluating a patient with altered mental status in cirrhosis

Diagnosis of HE

HE is a clinical diagnosis made by identifying acute changes in mentation in a patient with advanced liver disease. Though ammonia levels have been traditionally used to identify HE, they are not diagnostic. As described in a recent ‘Why-Series’ post linked here, serial ammonia measurements do not have a role in management of HE. Ammonia however can be a potential tool to exclude HE, as low levels may instigate the search of an HE-mimicker.

Management of HE

The cornerstone of HE management is identifying the underlying cause and managing the provoking factor in a timely fashion.

Lactulose is the first-line pharmacotherapy. A non-absorbable disaccharide, lactulose reduces intestinal production and absorption of ammonia through different mechanisms, as explained in a previous ‘Why-Series’ post, linked here. It should be titrated to obtain a goal of three soft bowel movements daily. Rifaximin is another treatment that can be added when lactulose proves ineffective or if a patient has recurrent presentations for HE. It has activity against the ammonia-forming microbes in the gut. Unlike other antibiotics, it concentrates in the GI tract, with minimal systemic absorption, reducing the likelihood of promoting bacterial resistance.

It is a common misconception that cirrhotic patients should be protein-restricted to prevent worsening of an ammonia load. Optimizing nutrition is crucial in management of the body’s nitrogen balance. Sarcopenia is a significant negative prognostic factor in patients with cirrhosis, and patients with cirrhosis need 1.2-1.5 g/kg of protein a day. It is advisable to provide small, evenly spaced meals or liquid nutritional supplements throughout the day, along with a high protein snack late at night.

Summary

Hepatic encephalopathy represents a complex interplay between liver dysfunction and brain health. Its clinical spectrum ranges from subtle cognitive impairments to severe neurological decline, significantly impacting patient survival and quality of life. A wide differential diagnosis must always be considered in a patient with cirrhosis and altered mentation. Effective management hinges on prompt identification of precipitating factors and their specific treatment strategies. Targeted pharmacotherapy includes a bowel regimen, lactulose, and possibly rifaximin. Remember, constipation is a diagnosis of exclusion in HE!

The role of patient and caregiver education in recognizing early symptoms and managing treatment cannot be overstated. As research continues to evolve, especially in the realms of diagnostics and emerging therapies, a multidisciplinary approach remains key to improving outcomes in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Don’t forget to check out our Quick Tip sheet on HE, linked here!

Take home

- The pathophysiology of HE includes the intersection of the gut-liver-brain axis, most commonly citing ammonia, but other pathways continue to be investigated.

- Considering a wide differential diagnosis in order of acuity based on the clinical presentation is paramount.

- Correcting and controlling the precipitating factor(s) is the cornerstone of HE management.