Why do we treat autoimmune hepatitis with immunomodulators?

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a relatively rare chronic, autoimmune disorder of the liver with rising prevalence in the United States and globally. Since its identification in the mid-twentieth century, glucocorticoids and azathioprine have been the mainstay treatments for patients with AIH—but why?

Let’s start with what we know about AIH—how do we diagnose AIH?

Patients with AIH range from being asymptomatic with abnormal liver tests (typically with hepatocellular injury evidenced by elevations in aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]) to having acute liver failure. Symptoms do not always correspond to inflammation severity, as asymptomatic patients may have similar degrees of histologic inflammation to those with symptoms (nausea, vague abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss, joint pain). Diagnostic criteria include characteristic histologic abnormalities, elevations in AST, ALT, total immunoglobulin levels, and the presence of autoantibodies.

What causes inflammation in AIH?

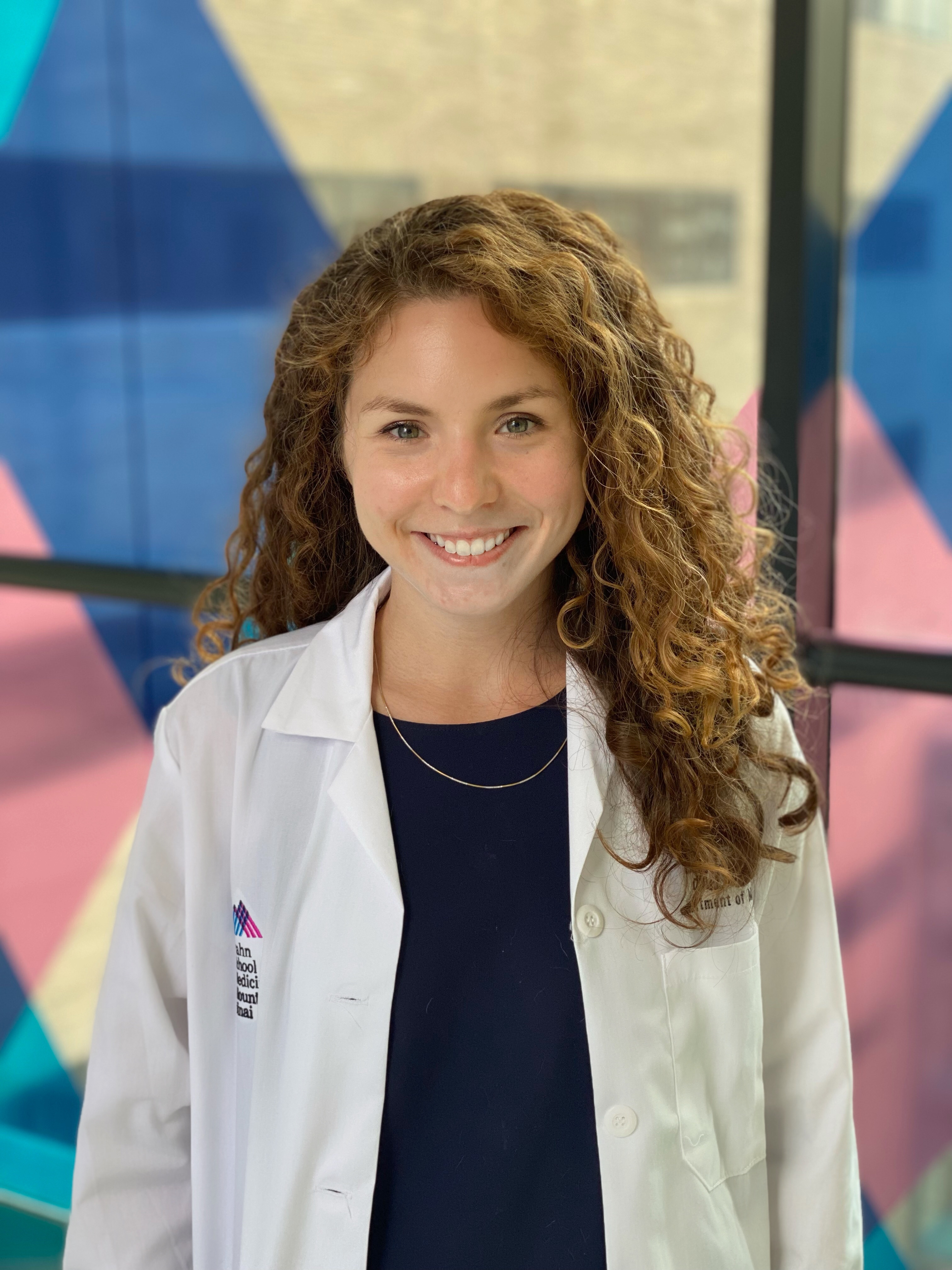

Inflammation in AIH is immune mediated. There are several identified genetic polymorphisms associated with AIH (largely in genes that transcribe immune cells and cytokine production), but epigenetic and environmental exposures are thought to be significant contributors to the development of clinically significant disease. There are many complicated inflammatory pathways leading to direct damage to hepatocytes in AIH (Figure 1, originally published in 2019 AASLD AIH guidelines, depicts an overview of the different cell types, cytokines, and interactions involved in AIH inflammation).

- T-regulatory cells (Tregs) train and control CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to prevent autoreactivity. Disruption in Tregs function (from viral/environmental triggers) makes them unable to prevent autoreactive CD4+/CD8+ T cells from activating and proliferating. These activated T cells bind to the liver and trigger an inflammatory cascade within the liver (leading to the characteristic histologic findings- interface hepatitis, emperipolesis and attempts at regeneration through rosette formation).

- Damage to the liver releases more liver antigen peptides into the body for class I and class II HLA molecules to find and present to both T cells (which perpetuate the inflammatory cascade causing direct attack on the liver) and B cells (which then start to secrete pathogenic auto-antibodies and activate natural killer [NK] cells).

Figure 1. Inflammatory pathways in AIH.

Figure adapted from the 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines from the American Association of for the Study of Liver Disease, Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children.

Who gets treated for AIH?

Very few patients will have resolution of inflammation without treatment (only about 12%). Even in asymptomatic patients, up to 70% will develop symptoms of AIH (or cirrhosis, the consequence of its progression) within 10 years, and those not treated will have a decreased 10-year survival compared to symptomatic patients with AIH who start treatment. So for most people, understanding medical treatment options is relevant. For some people who cannot tolerate the medications we use for treatment, or who are so sick that they need liver transplantation, medication can be stopped or skipped altogether. Those with mild disease phenotype who elect to defer treatment should be monitored closely with regular labs.

The goal of treatment is ultimately to prevent cirrhosis and its complications, which develop as a consequence of long cycle of inflammation and regeneration, which leads to the development of scar tissue in the liver. We monitor for signs that inflammation is decreasing both with labs and, sometimes, serial biopsies, and refer to them using the terminology below:

| Biochemical remission | Normalization of AST, ALT, IgG levels (may remain elevated in patients with cirrhosis) |

| Histological remission | Absence of histologic inflammation after treatment |

| Incomplete response | Improvement insufficient to satisfy remission criteria; ~15% of patients |

| Treatment failure | Adherent to standard therapy with worsening laboratory or histological inflammation; ~7-9% of patients |

Even though we use the term remission, most patients will require chronic medications to prevent recurrent inflammation.

How do we treat AIH?

The mainstays of AIH therapy have not changed so much since this disorder was first described and treated in the 1960s – glucocorticoids and antimetabolites. At that time, it was understood to be an inflammatory condition associated with autoimmune disease (mainly described in females with systemic lupus erythematosus and initially referred to as “chronic hepatitis” or “lupoid hepatitis”). A number of antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and surgical approaches were tried, including glucocorticoids, azathioprine (AZA), and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), with the last three demonstrating enough beneficial effect to continue their exploration and use until today.

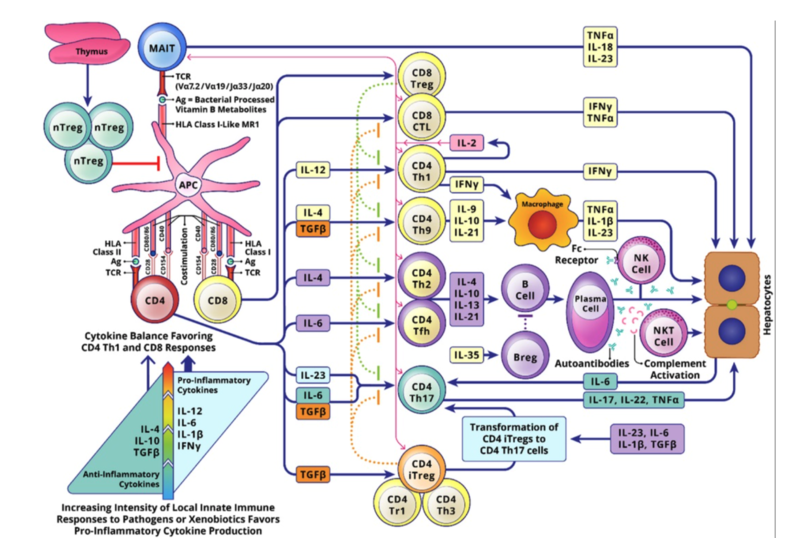

The AASLD and EASL guidelines are similar in their recommendations for first- and second-line treatment of AIH. The picture in Figure 2 is the AASLD’s recommended treatment algorithm.

Figure 2. 2019 AASLD First-Line AASLD Treatment Algorithm.

Figure adapted from the 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines from the American Association of for the Study of Liver Disease, Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children.

Before getting into more detail about specific treatment regimens for AIH, let’s first review what is understood about the pathophysiology of AIH to help us understand why these medications might work.

How do the mainstays of AIH treatment interact with the understood mechanisms of inflammatory damage in AIH?

Glucocorticoids

The most recent American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines for AIH diagnosis and management from 2019 and 2015 respectively recommend a trial of glucocorticoids (prednisone, prednisolone, or budesonide) for two weeks and close laboratory monitoring for signs of response (as measured by decreased serum AST/ALT/IgG). About 70-80% of patients show some clinical response to glucocorticoids, which act on multiple targets to exert both anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects that mitigate damage from autoimmune processes.

Budesonide has 90% first-pass hepatic metabolism, and therefore has less systemic absorption beyond the intestinal tract and the liver, reducing the risk of glucocorticoid toxicity with high doses or long-term use. At the time of the AASLD guidelines, adequate data for budesonide as the preferred glucocorticoid was also lacking. However, a number of studies since then have evaluated the efficacy of budesonide with azathioprine for inducing remission and show consistent safety and efficacy.

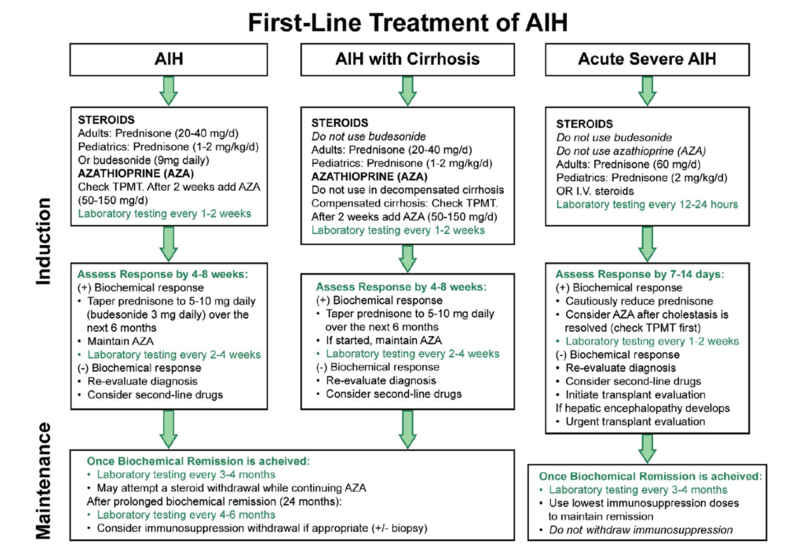

A double-blind RCT comparing patients treated with AZA and either prednisone 40mg daily tapered to 10mg daily or budesonide 3mg three times daily tapered to 3mg two times daily showed higher rates of serologic remission at six months (47% vs 18.4%, p<0.01) and lower rates of steroid-specific side effects (29% vs. 53%) in patients treated with budesonide vs. prednisone. All patients were then switched to budesonide for an additional six months and those who were switched from prednisone to budesonide had decreased risk of steroid-specific side effects.

Figure 3. Originally published in Manns MP, Woynarowski M, Kreisel W, et al.

Budesonide induces remission more effectively than prednisone in a controlled trial of patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. Oct 2010;139(4):1198-206. (A) Complete response (defined as serum AST and ALT within normal range and absence of steroid-specific side effects) for the intention-to treat (ITT) and per protocol (PP) populations. (B) Complete response rate at month 6 according to gender. (C) Complete response rate at month 6 according to baseline aminotransferase level. (D) Complete biochemical remission rate at month 6 compared with the biochemical remission defined as ALT activity 2x upper limit of normal at month 6.

However, since the goal for AIH treatment is to transition to steroid-free regimens after a relatively short period, and subsequent (retrospective) data has not clearly shown superiority of budesonide to prednisone/prednisolone, many people reach for budesonide in patients for whom they have a greater concern for steroid-specific side effects but otherwise use prednisone or prednisolone.

Importantly, budesonide has not ben studied in cirrhosis or severe acute liver injury/failure. There has been some demonstrated mortality benefit using prednisone and prednisolone in patients presenting with acute severe AIH or AIH-associated acute liver failure (ALF), although patients in both groups are likely to require liver transplantation and steroids should be stopped after a relatively short trial period without significant improvement to reduce the risk of infectious complications.

Azathioprine

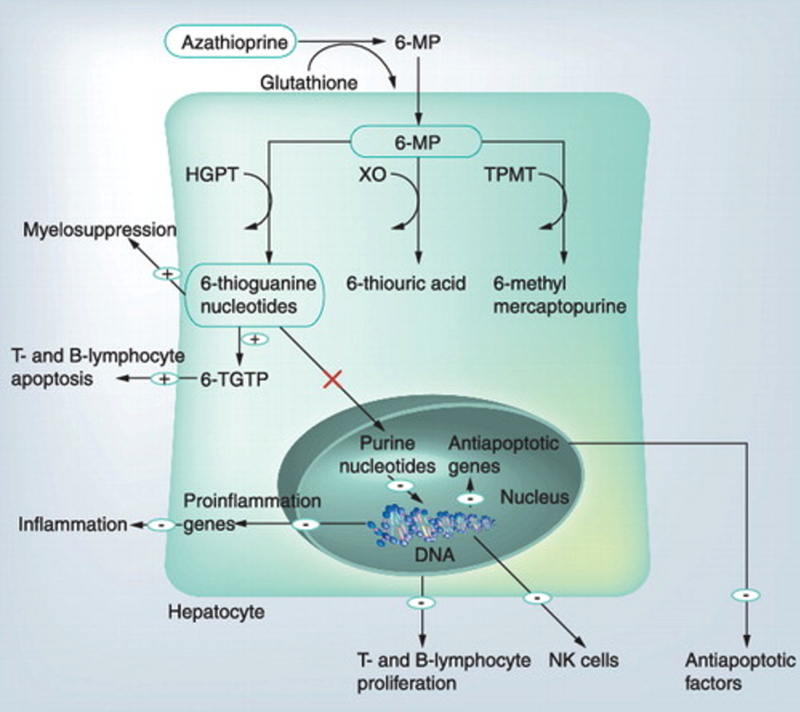

Azathioprine was first synthesized as a pro-drug of 6-MP in 1957 as an anti-metabolite intended for use in cancer. Notes show that rabbits given 6-MP had decreased levels of autoantibodies in response to various antigens, and therefore explored further as an immunosuppressive to prevent graft rejection in liver transplant. After oral ingestion, it is absorbed throughout the entire GI tract and enters cells of the intestinal epithelium, liver, and red blood cells, where it is converted to 6-MP. 6-MP is metabolized through two competing pathways (Figure 4)—one which results in cytotoxic thioguanine nucleotides (the “goal” product of AZA, as these cytotoxic nucleotides inhibit purine synthesis and lymphocyte replication, but also prevent other important cell replications using the same “de novo synthesis” pathway), and one in which TMPT and xanthine oxidase convert 6-MP to nontoxic metabolites. In the absence of normal TPMT activity, patients on AZA can experience significant toxicity from too much shunting down the cytotoxic pathway, and so TPMT levels are often checked prior to drug initiation.

Figure 4. AZA/6-MP mechanism.

Figure initially published by Czaja, A. J. (2012). Drug choices in autoimmune hepatitis: Part B – nonsteroids. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 6(5), 617–635.

A series of prospective trials adding AZA to glucocorticoids and various dosing schedules of AZA maintenance regimens was done in the ‘80s; these showed sustained remission without introducing the toxicity of chronic glucocorticoids. Since then, subsequent retrospective studies have demonstrated consistent benefit, with sustained remission in about 80% of patients with ongoing use after steroid induction. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of AZA metabolites (maintaining adequate levels of therapeutic 6TGNs and low doses of toxic 6MMP), though not standard practice everywhere, has been shown to be associated with higher rates of sustained complete biologic remission compared to weight-based dosing for AZA maintenance. An international European cross-sectional analysis of 337 patients demonstrated higher likelihood of achieving therapeutic levels of 6TGNs (≥223 pmol/0.2ml in a recent study of AIH which is consistent with targets of 230-260 found in larger studies in inflammatory bowel disease and connective tissue diseases) and complete biologic response when TDM strategies were used, and also suggested that the addition of allopurinol to shunt AZA away from the xanthine oxidase metabolism pathway also improved 6TGN levels in patients with initial inadequate response to AZA. Split-schedule dosing of AZA has also been shown to result in increased 6TGN production in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, and is therefore sometimes used in patients with AIH.

Of note, given the demographics of patients affected by AIH, special consideration should be given to the management of AIH in pregnancy. Both glucocorticoids and AZA are considered safe to continue preconception, during pregnancy, and while breastfeeding, and better AIH control going into pregnancy portends better fetal and maternal prognosis during and after pregnancy.

Mycophenolate

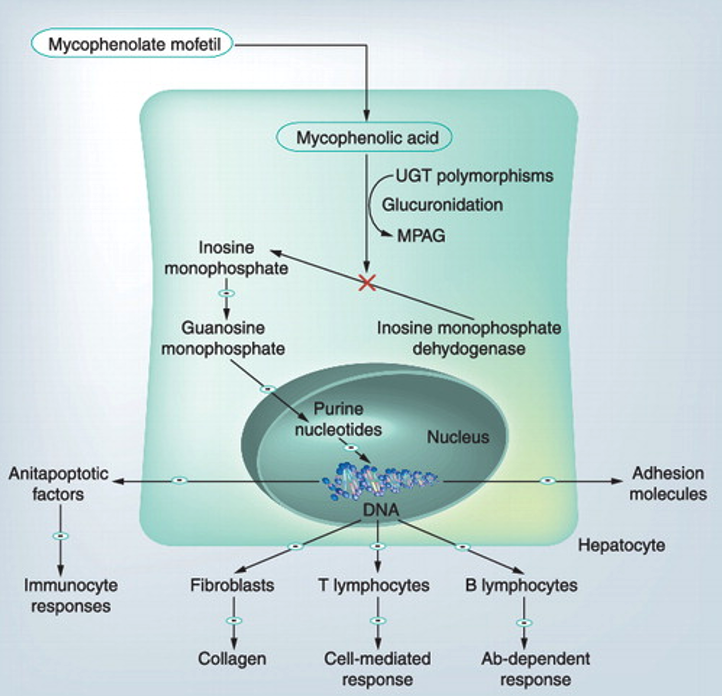

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and mycophenolate sodium (the enteric coated formulation) are pro-drugs of mycophenolic acid (MPA). MMF is almost completely absorbed in the small bowel and is converted to MPA, which is then converted to phenolic glucuronide and excreted in the urine (this metabolite is largely responsible for GI side effects, so changing to the enteric coated version can reduce these symptoms by slowing absorption and build-up of the glucuronide metabolite; the renal excretion is the reason that MMF needs to be renally dosed).

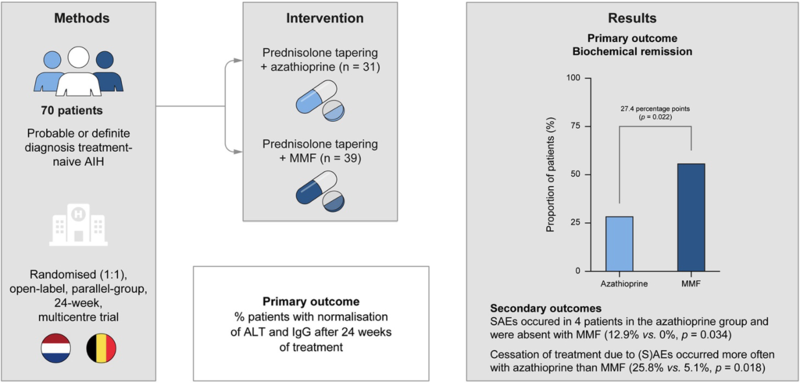

Similar to AZA, MPA inhibits de novo purine synthesis by preventing guanine nucleotide formation (Figure 5). Although AZA is currently positioned first in the AASLD and EASL guidelines (with MMF as recommended second-line therapy), the recent CAMARO study reported a prospective RCT of 70 treatment-naïve patients with AIH receiving AZA vs. MMF and showed significantly increased likelihood of biologic remission at six months in the MMF group compared to AZA (56.4% vs 29%, p=0.022) (Figure 6). In contrast to azathioprine, MMF is considered both teratogenic and abortogenic and should be held for six weeks prior to conception and throughout pregnancy.

Figure 5. MMF mechanism.

Figure initially published by Czaja, A. J. (2012). Drug choices in autoimmune hepatitis: Part B – nonsteroids. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 6(5), 617–635.

Figure 6. Originally published in Snijders R, Stoelinga AEC, Gevers TJG, et al.

An open-label randomised-controlled trial of azathioprine vs. mycophenolate mofetil for the induction of remission in treatment-naive autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. Apr 2024;80(4):576-585.

Other Medications

Only small studies of third line agents for AIH exist. Retrospective case series (<300 total patients) of tacrolimus and cyclosporine in patients who had inadequate response or intolerable side-effects to first-line therapy show reasonable safety, tolerability, and efficacy profiles, with about 50% of patients achieving remission after failed first-line therapy. Anti-CD20 agent, rituximab, was used as third-line in 22 patients in a European case series with reduced glucocorticoid requirement, decreased serum inflammatory markers, and fewer flares over a 2 year period in >50% of patients. Anti-TNF agents such as infliximab have also been used in patients with AIH with some benefit in AST/ALT, though anti-TNF-induced AIH-like disease has also been documented. Naloxone has also been studied in animal models as a modulator of the NFKB inflammatory pathway decreased ALT/AST, measured cytokine levels, and histologic inflammation.

What’s next?

18 clinical trials studying autoimmune hepatitis medications are currently recruiting (clinicaltrials.gov, August 11, 2024). The most commonly used medications currently target different parts of the AIH pathophysiology as we currently understand it. However, since AIH has such variable presentation and progression, a better understanding of which of the multiple inflammatory mechanisms are at play in which patients may allow for more targeted use (and withdrawal) of medications.