Why Should We Prescribe Medications to Treat Alcohol Use Disorder?

The prevalence of alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is increasing. Still, few gastroenterology (GI) and hepatology providers are prescribing medications to help patients decrease alcohol consumption and maintain sobriety Pharmacologic interventions are a recommended treatment for moderate to severe alcohol use disorder (AUD) and most are safe for use in patients with liver disease. Co-managing patients with an addiction medicine provider is ideal, but not always an available model of care. Further, many primary care and psychiatry providers worry about prescribing medications for patients with cirrhosis or who are post-transplant due to concerns about poor hepatic metabolism or adverse reactions. There is a role for hepatologists to lead by example in treating AUD and educating our colleagues about the indications for and safety of these medications. Treating AUD also gives hepatologists an opportunity to engage in the empowering practice of preventing the downstream effects of excess alcohol use rather than just treating progression of disease and decompensation. This post seeks to outline the evidence for using medications to treat alcohol use disorder in patients with liver disease and introduce our current medication options.

Definitions

Risky/Hazardous Drinking vs Alcohol Use Disorder

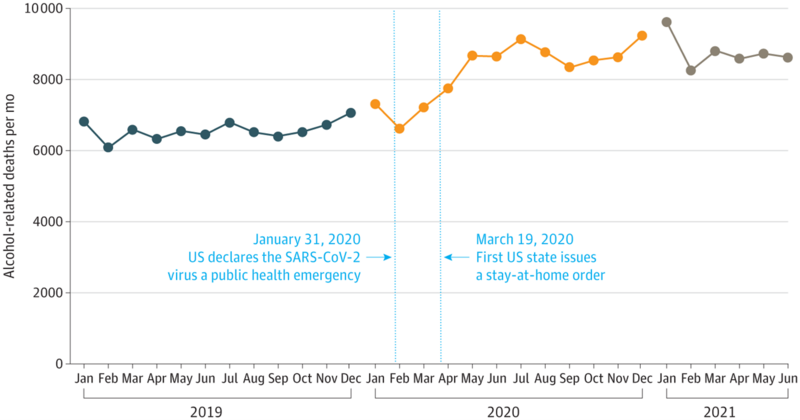

The definition of “risky” or “hazardous” alcohol use is drinking more than the recommended amount of alcohol thus increasing one’s risk of developing adverse health effects related to drinking. This is defined by the United States Preventative Task Force as more than 4 drinks in one sitting or 14 drinks per week for an adult male, and 3 drinks in one sitting or 7 drinks per week for an adult female (Figure 1). A drink is 14g of alcohol (12 oz beer or 5 oz glass of wine) . These guidelines should be interpreted with caution given that even mild alcohol use can contribute to progression of steatosis and fibrosis in patients with underlying liver disease, specifically metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), which is increasingly prevalent and underdiagnosed. Further, the American Cancer Society stresses that there is no “safe” level of alcohol use as even less than 1 drink per day can increase one’s risk of cancer.Hazardous drinking is distinct from alcohol use disorder (AUD), which is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual- V as drinking that leads to significant distress manifested as cravings, withdrawal, an inability to cut back on drinking despite efforts to do so, and/or continuing to drink despite harmful effects on one's health, relationships, or employment.

Figure 1: USPSTF recommended limits on alcohol use. Figured adapted from Indiana SBIRT (https://indianasbirt.org/patients-improve-health).

Diagnosing Alcohol Use Disorder

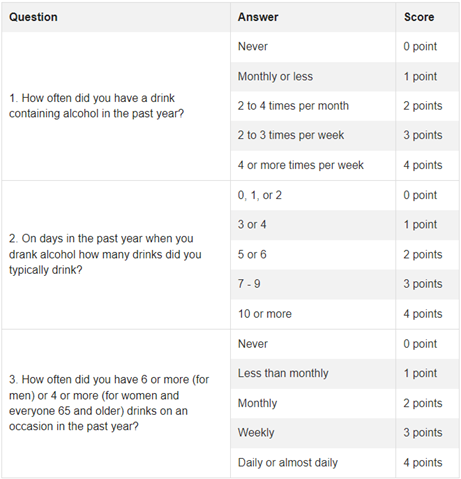

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a 10-question survey tool for diagnosing AUD but it takes more time to complete than many clinical settings can accommodate. The AUDIT-C (Figure 2) is a 3-question survey that is a validated screening tool with comparable sensitivity to the AUDIT. Women with an AUDIT-C score >3 and men with a score >4 are considered to have alcohol use disorder. This and many other screening tools may lack specificity and be falsely positive for patients who drink frequently but do not have alcohol use disorder; however, these patients will likely still benefit from interventions to support a decrease in alcohol use or maintaining sobriety.

Figure 2: AUDIT-C tool for screening for alcohol use disorder. A positive screen is an AUDIT-C greater than 3 for women and greater than 4 for men. Figure adapted from hepatitis.va.gov/alcohol/treatment.

The use of biomarkers (detectable metabolites or surrogates of alcohol use in the blood or urine) can be helpful in diagnosing significant alcohol use or in monitoring response to treatment of alcohol use disorder. Urine ethyl glucuronide (EtG) detects alcohol use in the preceding 3 days whereas serum phosphatidylethanol (PeTH) detects alcohol use in the last 2-3 weeks or longer with chronic, heavy alcohol use. These tests have limitations and should not be used alone to diagnose hazardous drinking, but rather in conjunction with the patient interview and other biomarkers such as AST and GGT. It is recommended to discuss the use of biomarkers with patients before testing, and to frame them as a tool to support recovery and monitor response to treatment rather than to “catch” surreptitious alcohol use.

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome (AWS)

Patients starting medications for alcohol use disorder and abruptly decreasing their use of alcohol can experience alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS). Withdrawal symptoms typically develop in the 6-12 hours after cessation of alcohol; mild symptoms include anxiety, irritability, nausea, headache, tachycardia, and can progress to more severe symptoms of tremor, confusion, and hallucinations. Severe withdrawal can be life-threatening, whereas mild to moderate withdrawal can be safely managed in the outpatient setting. Patients at a high risk for severe withdrawal are patients with a history of severe or complicated withdrawal (experiencing delirium tremens, seizures, confusion, or hallucinations or requiring inpatient symptom management) and patients with a history that supports heavy alcohol use (frequent episodes of intoxication or blackouts, regularly drinking >8 drinks per day). Providers prescribing medications for alcohol use disorder should screen for these risk factors and refer to an addiction medicine provider for AUD management if a patient is at high risk for severe AWS.

Baclofen, gabapentin, and topiramate can be effective in treating symptoms of mild AWS and are safe in most patients with liver disease while also being useful in treating alcohol cravings and preventing relapse. Gabapentin specifically has been shown to decrease rates of relapse in patients with a history of alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

Why should hepatologists be involved in treating alcohol use disorder?

- The burden of alcohol-related liver disease is increasing.

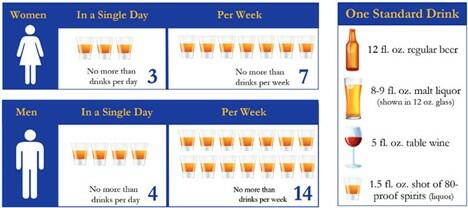

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is prevalent globally with 60% of cirrhosis cases in Europe, North America, and Latin America being attributed to alcohol. Deaths related to alcohol-related liver disease have increased in the United States (US) in the last decade, with an acceleration in the rise in ALD mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 4). There are no targeted therapies to halt the progression of alcohol related liver disease other than abstinence from alcohol, thus supporting patients in achieving alcohol cessation is the first-line therapy for ALD.

Figure 4: Alcohol-related deaths during the COVID 19 pandemic. There was a significant increase in alcohol-related mortality starting around March 2020, corresponding to the US declaration of a public health emergency and stay-at-home orders. Figure adapted from White et al.

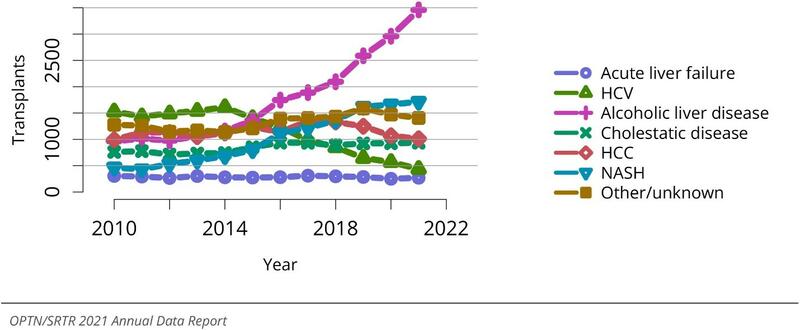

More than 40% of liver transplant listings in the US are for ALD – a proportion that is rising with the increase in transplants performed for acute alcohol associated hepatitis (Figure 5). Maintaining sobriety after transplant is paramount to graft survival and many post-transplant patients benefit from pharmacologic support for maintaining abstinence.

Figure 5: Total liver transplants by diagnosis. There has been a significant increase in the number of transplants performed annually for alcohol-related liver disease in the past decade. Figure adapted from the OPTN/SRTR Annual Data Report from 2021.

- Medications for AUD are effective

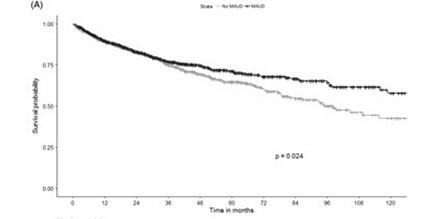

Medications for alcohol use disorder are effective at decreasing heavy drinking, preventing alcohol relapse, and decreasing rates of alcohol related adverse health outcomes. A recent meta-analysis that included 118 clinical trials and over 20,000 patients found that acamprosate, naltrexone, and baclofen were associated with a statistically significant decrease in rates of returning to alcohol use when prescribed to treat alcohol use disorder. Studies have shown prescribing medication for alcohol use disorder to patients at discharge from a hospitalization related to overuse of alcohol is associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality and ED admissions or re-hospitalizations in the 30 days after discharge. Regarding ALD specifically, a large retrospective cohort study of over 9000 patients with alcohol use disorder found a strong association between receiving pharmacologic treatment for alcohol use disorder and a lower odds of developing ALD. For patients in this cohort with cirrhosis, there was an association between pharmacologic treatment for alcohol use and lower odds of developing hepatic decompensation. Another recent retrospective study of US Veterans with alcohol related cirrhosis and at-risk drinking found that exposure to acamprosate, naltrexone, or both within the first year after cirrhosis diagnosis was associated with improved long-term survival.

Figure 6: A Kaplan-Meier analysis from a large cohort of US veterans with alcohol-related cirrhosis and at-risk drinking comparing the survival curve among patients who received medications for alcohol use disorder (MAUD) in the first year after diagnosis of cirrhosis versus propensity score–matched controls. Figure adapted from Rabiee et al.

- Medications for alcohol use disorder are under utilized

Despite demonstrated efficacy, few patients with alcohol use disorder receive pharmacologic treatment. A 2023 study of Medicare beneficiaries found that of 28,602 hospital admissions for a diagnosis related to alcohol use, only 1.3% of patients received a prescription for pharmacologic treatment for alcohol use disorder in the 30 days after discharge. In a cohort of over 9000 US Veterans with cirrhosis and at-risk drinking, only 9% received medication for alcohol use disorder in the first year after cirrhosis diagnosis. This low uptake in prescribing of pharmacologic treatment for alcohol use disorder, particularly for patients with cirrhosis, may be due to fear of side effects or triggering decompensation, lack of a follow-up plan for drug monitoring, or lack of knowledge of the indication for prescribing medications for AUD or of medication options. In a survey of hepatology and gastroenterology providers, 71% of providers had never prescribed treatment for alcohol use disorder, mostly due to low comfort with the medications and lack of addiction medicine training.

- Medications for AUD are safe and well tolerated in patients with liver disease

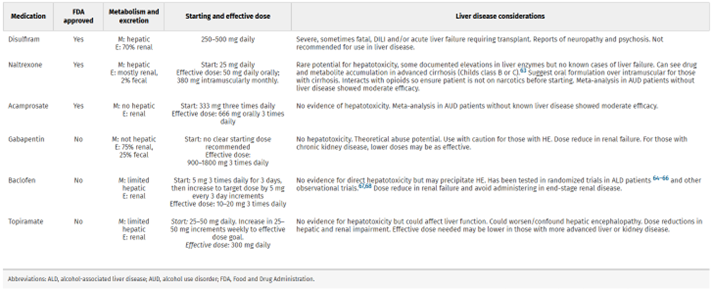

Patients with cirrhosis were largely excluded from initial safety trials of medications for alcohol use disorder, but there are increasing data supporting the safety of these medications in patients with liver disease. The three FDA approved medications for alcohol use disorder are naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. Medications that are used off-label for AUD include baclofen, gabapentin, varenicline, topiramate, prazosin, and ondansetron. Of this list, disulfiram is the only medication that is contraindicated in patients with liver disease given complete hepatic metabolism and potential hepatotoxicity. So, what should we know about the medications that we CAN use in patients with liver disease?

Figure 7: A summary of medications for treating alcohol use disorder and important prescribing considerations for patients with liver disease. This table was adapted from Mellinger et. al.

Acamprosate

The exact mechanism whereby acamprosate decreases alcohol use is unknown, but it’s hypothesized that it modulates hyperactive glutamatergic NMDA receptors. It is dosed at 666mg three times daily. Acamprosate has been shown to be safe for patients with cirrhosis, though studies of its safety in patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis are limited. Acamprosate is renally cleared, thus it is not recommended in patients with mild to moderate renal impairment, or if used, there is a recommended dose decrease to 333mg three times per day. It is contraindicated in severe renal impairment.

Naltrexone

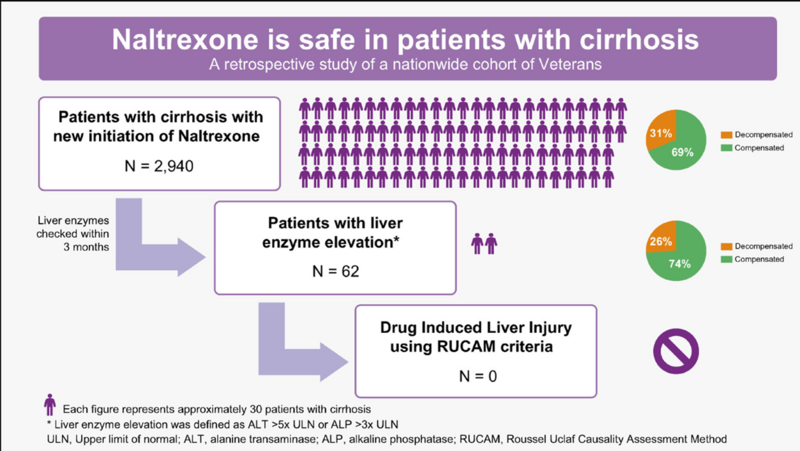

Naltrexone is a mu-opioid antagonist that decreases the dopamine surge that results from alcohol intake. It is available in oral form dosed at 50mg daily, or in a long-acting injectable form dosed at 380mg monthly. The most common side effects include nausea, dizziness, and fatigue. There was a previous FDA black box warning for naltrexone in patients with liver disease due to concern for hepatotoxicity; however, given a lack of reported cases of significant hepatic injury related to naltrexone, this black box warning was removed in 2013. Several subsequent studies have supported the safety of naltrexone in patients with liver disease. A retrospective cohort of 160 patients who were prescribed naltrexone for alcohol use disorder found no events of liver injury or hepatic decompensation attributable to naltrexone in patients with or without liver disease. A retrospective study that included 2,940 US Veterans who were prescribed naltrexone after a diagnosis of cirrhosis found that only 2% had significant enzyme elevations after starting naltrexone. Based on the Roussel Uclaf causality assessment method (RUCAM), none of these cases were deemed probable or highly probable of being attributed to drug induced liver injury (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Results of a large cohort study of US Veterans with cirrhosis prescribed naltrexone. No cases of drug induced liver injury were detected. Reproduced from Thompson et al, 2023.

Baclofen

Baclofen treats alcohol cravings through its mechanism as a GABA agonist. It is dosed at 5mg three times daily, increased every 5-7 days as tolerated to max dosing of 15mg three times daily. There are several studies supporting the safety of baclofen use in patients with liver disease including a small, randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of 84 patients with cirrhosis, which showed that patients who received baclofen were more likely to remain sober from alcohol as compared to patients who received placebo. There were no adverse hepatic events during the study. However, subsequent studies have had mixed results in terms of the efficacy of baclofen for reducing alcohol use. An RCT that included 180 patients with hepatitis C and concurrent AUD found that treatment with baclofen was not associated with a significant decrease in alcohol use. Baclofen does have a notable side effect of sedation and drowsiness and should be used with caution in patients with a history of hepatic encephalopathy. A large, retrospective cohort study showed an increased risk of hospitalization and death in patients prescribed baclofen as compared to those prescribed acamprosate, naltrexone, or nalmefene. Specifically in patients with Childs-Pugh B or C cirrhosis, Tyson et al found that patients prescribed baclofen had a greater number of unplanned hospital visits compared to patients prescribed acamprosate. In summary, there are mixed results on the efficacy of baclofen for the treatment of AUD, but it can be trialed in patients with compensated cirrhosis.

Gabapentin

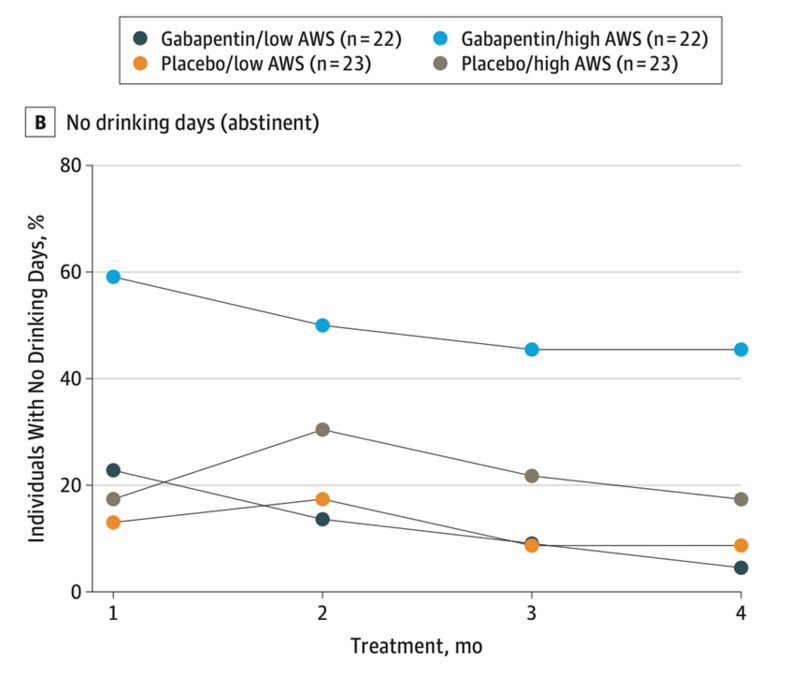

Gabapentin is a structural analog of the GABA neurotransmitter that treats alcohol use disorder and alcohol withdrawal through increasing the release of GABA and decreasing release of glutamate, thus decreasing central nervous system excitability during alcohol withdrawal and alcohol craving. Recommended dosing is 900 to 1800mg daily in divided doses. It is renally cleared and there is specific renal dosing based on degree of renal impairment. In the general AUD population, several studies have shown gabapentin to be effective in increasing rates of abstinence and decreasing rates of relapse to heavy drinking particularly in patients with a history of alcohol withdrawal. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of gabapentin for treating alcohol use disorder in patients with a history of withdrawal found that gabapentin was associated with lower rates of returning to drinking as compared to placebo with a greater benefit experienced by patients reporting more withdrawal symptoms at the beginning of the study (Figure 9). There is minimal hepatic metabolism, thus it has a favorable safety profile in patients with liver disease. A large cohort study of patients with alcohol use disorder found that patients with cirrhosis who were prescribed gabapentin for AUD were less likely to experience cirrhosis decompensation.

Figure 9: The percent of patients with no drinking days (or maintained abstinence) who received gabapentin vs placebo for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Patients who reported more symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome at the start of the study (high AWS) were more likely to remain abstinent as compared to patients receiving placebo, or patients who had fewer alcohol withdrawal symptoms (low AWS). This figure was adapted from Anton et al, 2020.

Topiramate:

Topiramate is an anticonvulsant medication with several potential mechanisms by which it treats alcohol use disorder, including positively modulating GABA-A receptors in the brain, leading to a decrease in the positive reinforcing effects of alcohol consumption. It is titrated up from 25 to 50mg daily as tolerated to a maximum dose of 400mg daily. Potential side effects include paresthesia, kidney stones, glaucoma, cognitive impairment, and weight loss. There are notable randomized, double-blinded, controlled trials showing topiramate as more effective than placebo at decreasing the percentage of heavy drinking days in patients with hazardous drinking habits (AUDIT >8). Exposure to topiramate has been associated with a decreased risk of developing ALD in patients with alcohol use disorder, but there are limited data on its effectiveness and safety in patients with cirrhosis. Given that topiramate does have some hepatic metabolism and it has not been well studied in patients with liver disease, it is recommended only for use in patients with compensated cirrhosis and with close monitoring for the development of side effects.

Conclusions:

Alcohol-related liver disease has increasing prevalence globally, and first line therapy is interventions to decrease alcohol use, which includes effective pharmacotherapy. As specialists treating liver disease, we should feel empowered by the available data on the efficacy and safety of medications for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with liver disease and cirrhosis. Prescribing medications for alcohol use disorder should include accurate diagnosis of alcohol use disorder using screening questionnaires such as the AUDIT-C, as well as monitoring for and treating symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Recommended medications for alcohol use disorder in patients with liver disease include acamprosate, naltrexone, baclofen, gabapentin, and topiramate.

Key Points:

- Alcohol-related liver disease is increasingly prevalent and abstinence from alcohol is the only available treatment to prevent progression of alcohol-related liver injury.

- Medications for alcohol use disorder are underutilized and hepatologists have an important role in reassuring providers in other disciplines that these medications are safe for patients with liver disease.

- Acamprosate, naltrexone, and baclofen are the medications with the most data supporting safety and efficacy in patients with liver disease.

- Gabapentin can be used to treat symptoms of mild alcohol withdrawal in addition to treating cravings for alcohol.