Why the 6-Month Sobriety Rule for Liver Transplantation Is Being Abandoned: Evolution in Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease Care

What is the current state of alcohol liver disease?

Alcohol liver disease (ALD) represents a spectrum of conditions ranging from steatosis to steatohepatitis to cirrhosis, occurring as a consequence of alcohol use disorder (AUD). AUD is an escalating cause of mortality in the United States and worldwide, ranking as the third leading preventable cause of death in the United States and imposing an increasing economic burden. The rise in alcohol use, morbidity, and mortality has been especially significant among young adults aged 24-35.

The estimated prevalence of ALD is approximately 2% in the general U.S. population and 3.5% globally. This rate increases dramatically to 26.0% among hazardous drinkers and 55.1% among individuals with diagnosed alcohol use disorders. Alcohol cirrhosis (AC) specifically affects about 100 per 100,000 enrollees in privately insured populations and 327 per 100,000 in the U.S. Veterans' population. These numbers are projected to increase as global alcohol consumption continues to rise.

The economic impact of ALD is substantial and growing. Between 2012 and 2016, ALD cirrhosis hospitalizations alone cost $22.7 billion. Annual ALD-related expenses are forecast to increase from $31 billion in 2022 to $66 billion by 2040—a 118% rise. The cumulative cost over this 18-year period is expected to reach $880 billion, comprising $355 billion in direct healthcare expenses and $525 billion in lost productivity and economic consumption.

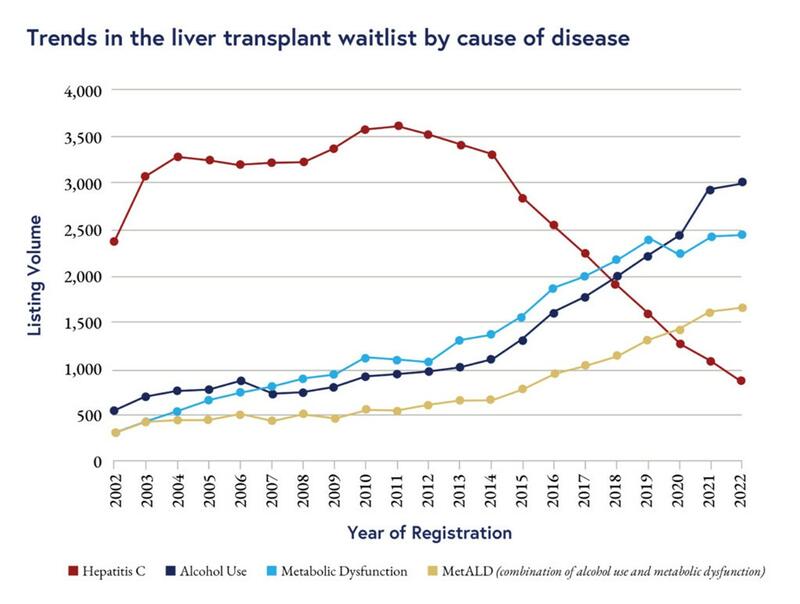

Historically, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was the primary indication for liver transplantation. However, with the development of direct-acting antivirals, the necessity for HCV-related transplants has significantly decreased. Currently, ALD and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD, formerly known as NAFLD) have become the leading indications for liver transplantation. Although some projections suggested MASLD would surpass ALD by now (with new estimations suggesting 2050), increased alcohol consumption during the pandemic and improved obesity medications may have altered this trajectory. As of 2023, ALD accounted for 41.1% of liver transplant recipients, followed by MASLD at 20.3%.

Figure 1: Trends in the liver transplant waiting list by cause of disease. Figure from: Ochoa-Allemant et al. Waitlisting and liver transplantation for MetALD in the United States: An analysis of the UNOS national registry. Hepatology. April 29, 2024. (https://journals.lww.com/hep/abstract/2025/02000/waitlisting_and_liver_transplantation_for_metald.20.aspx )

A Time Not So Long Ago

For those of us in training or early in our careers, we may take for granted current attitudes toward ALD. Currently, 1 in every 2 transplantations performed in the United States is for ALD. This was not always the case. Bias and stigma against these patients were once much more prevalent in both societal and medical contexts.

Liver transplantation (LT) was rarely performed for ALD until 1983, when the United States National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference on Liver Transplantation concluded that ALD is an appropriate indication for LT. This conclusion came with the requirement that patients must be deemed likely to abstain from alcohol. In 1984, the same year the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) was established, the National Institutes of Health consensus conference stated that few patients with ALD would be selected for LT. A retrospective study of patients at a community hospital in South Wales, United Kingdom from 1987 to 1990 revealed that ALD was the most common diagnosis among patients not referred to an LT unit, with continued drinking being the usual explanation.

This approach and attitude stemmed from multiple sources. There was a prevalent societal belief that ALD is a self-inflicted condition and thus a moral failing of the individual. Even within the medical community, persistent bias existed. A study found that a significant number of medical students, residents, fellows, and attending physicians either remained neutral or disagreed with equal transplantation rights for patients with ALD who discontinued drinking compared to those with MASLD who committed to weight loss programs. Some expressed concern that offering liver transplants to patients with ALD might lower public support for transplantation, thereby decreasing the donor pool. Patients themselves internalized stigma and shame, leading to delays in seeking treatment for alcohol use disorder and lack of early diagnosis of ALD. Many patients felt reluctant to discuss their AUD with healthcare providers or to ask for help. Finally, livers remain a limited resource, and allocating an organ to one patient often means another will not receive one.

What Was the 6-Month Rule?

Like many principles in medicine, the "6-month rule" began as a well-intentioned endeavor.

In the late 1980s, the Pittsburgh group under Thomas Starzl began challenging the idea of absolute exclusion with a landmark 1988 study that demonstrated 68% of patients with ALD who received a liver transplant were still alive after 7 years. Instead of being ignored, these patients were now being studied. Researchers examined the characteristics that seemed to predict the holy grail of post-transplant success: abstinence from alcohol. Predictive factors included: Self-recognition of alcohol dependence:

- A stable living environment with social support

- Absence of psychiatric disorders

- Access to resources that facilitate continued abstinence

Initial hospital protocols varied dramatically, ranging from as little as two months to as long as two years of required abstinence. In 1986, in Allen v. Mansour, a patient filed a lawsuit against the state of Michigan for refusing to offer him a liver transplant after 7 months of abstinence because they required a two-year abstinence period. The court deemed this requirement excessively long and arbitrarily determined, ruling that insurance must pre-authorize him for transplant.

The 6-month abstinence requirement was first mentioned in a 1984 Hepatology paper stating: "Liver transplantation should be offered only to those with verified abstinence for 6 months or longer." This recommendation stemmed from observational and retrospective studies that demonstrated worse outcomes for those who returned to drinking. One study emphasized that two patients had ongoing evidence of hepatitis on their explanted livers and thus could have benefited from a longer trial of abstinence. Researchers cited three additional patients who were not abstinent prior to transplant and subsequently relapsed, arguing that "selecting a patient under normal circumstances should include a period of abstinence of at least 6 months."

By the mid-1990s, the 6-month rule became firmly embedded in transplant programs. A 1997 survey found that 85% of U.S. programs required 6 months of abstinence prior to listing. In a 1997 report from the AASLD and the American Society of Transplant Physicians, the 6-month rule was endorsed as a reasonable requirement as it served dual purposes:

- It provided time for recovery from the acute inflammatory effects of recent alcohol exposure.

- It served as a demonstration of abstinence and a predictor of long-term sobriety.

Implementation and Issues

While the 6-month rule may not have been intended as a punitive measure, it certainly came to function that way for many patients. Transplant programs justified this policy by citing studies showing that approximately 30% of patients who did not observe the 6-month abstinence period eventually relapsed after transplantation. The legal system further entrenched this practice when it reaffirmed the constitutional legality of the 6-month rule in the case of Neal v. Christopher & Banks.

As liver transplantation for ALD grew in volume, several key issues emerged:

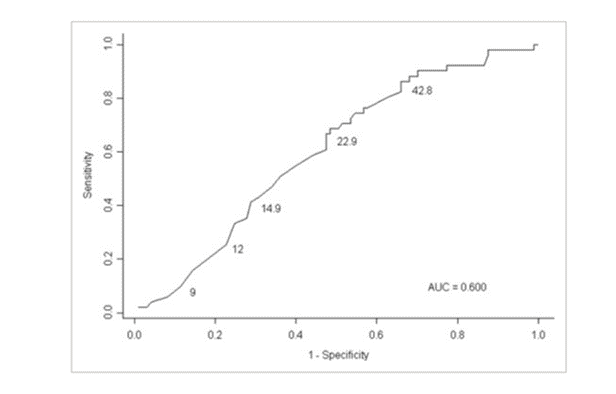

Poor predictive value of pre-transplant abstinence: Multiple studies demonstrated a poor correlation between the length of pre-transplant abstinence and post-transplant sobriety. One study showed that while the length of sobriety had reasonable sensitivity (80%), it had very poor specificity (40%). An area under the curve of 0.6 is hardly better than chance, as 0.5 represents a simple coin flip.

Figure 2: ROC curve for the prediction of relapse (single use) within 18 months of transplant using months sober prior to transplant (selected points on curve labeled with corresponding months sober pre-LTX). *The numbers on the curve are months of pre-LTX sobriety. Figure from: Andrea DiMartini et al. Alcohol Consumption Patterns and Predictors of Use Following Liver Transplantation for Alcoholic Liver Disease. Liver Transplantation.12:813-820, 2006. (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/lt.20688)

Healthcare disparities: Significant inequities in care became evident. Black patients and women with ALD had a higher listing-to-death ratio, suggesting unequal access to transplantation.

Inconsistent assessment protocols: There was a lack of standardization in psychosocial assessment protocols between centers. Each center relied on its own subjective determination criteria. At the time, no validated risk assessment tool existed (a topic we will explore further later).

Different standards across diseases: Transplant programs accepted different standards for outcomes for other etiologies of liver disease. There were higher rates of disease recurrence for other conditions such as hepatitis C (before the advent of direct-acting agents) and autoimmune hepatitis. Moreover, the outcomes for liver transplantation in ALD were comparable to or better than outcomes for non-ALD transplantation.

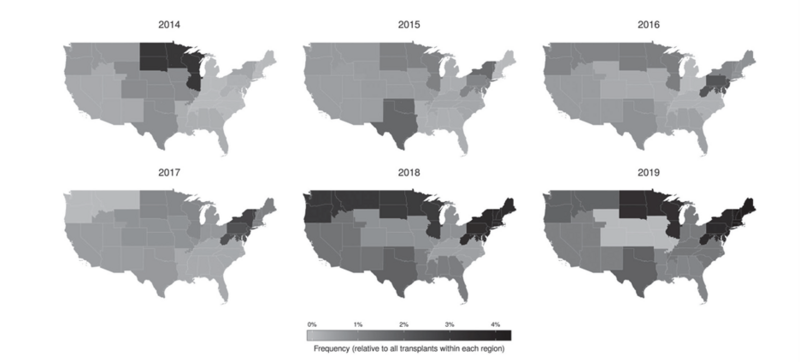

Institutional variation: Significant institutional variation existed in transplant and listing patterns. Some centers employed more flexible approaches while others remained rigid. In fact, when it came specifically to alcohol-associated hepatitis, regional variation was as high as 8-fold.

Speaking of alcohol-associated hepatitis...

Alcohol-associated hepatitis is an acute inflammatory syndrome that can occur in patients with alcohol-associated liver disease, ranging from mild to severe presentations. In severe alcohol-associated hepatitis, mortality rates can reach 50% at 28 days and 70% at 6 months for those unresponsive to corticosteroid treatment. With such high mortality rates, these patients would often die because they couldn't survive the 6-month abstinence period required to qualify for a transplant.

The Pivotal Study That Changed Hearts and Minds

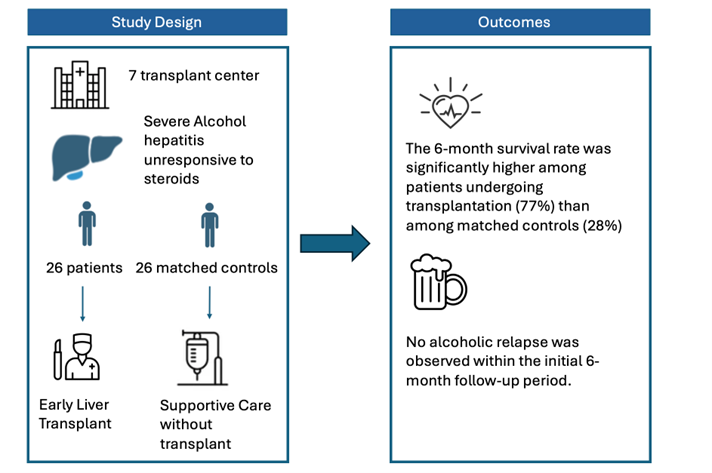

In a groundbreaking study conducted across seven transplant centers in France, a group led by Philippe Mathurin examined "early" liver transplantation for patients presenting with acute alcohol-associated hepatitis.

The study focused on patients with Maddrey's discriminant function >32 who failed to respond to steroid therapy (identified by Lille score ≥0.45 after 7 days or rising MELD scores). The selection criteria were exceptionally stringent: patients had to be experiencing their first episode of liver decompensation, have supportive family members, be free of severe psychiatric disorders, and demonstrate commitment to lifelong abstinence. Only approximately 2% of severe alcohol-associated hepatitis patients met these rigorous requirements.

The intervention group received liver transplantation before completing the traditional 6-month waiting period, while the control group—matched by age, sex, Maddrey's discriminant function, and Lille score—received standard care without transplantation. The study measured 6-month survival as the primary outcome and return to alcohol use as the secondary outcome.

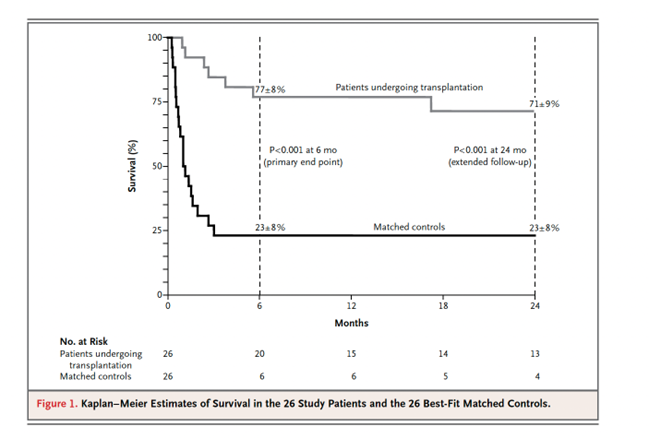

The results were undeniable. Twenty-six severely ill patients (median MELD score of 34) received transplants, typically within 9 days of listing. By the 6-month mark, 77% of transplanted patients had survived, compared to just 23% of the control group, with 90% of non-transplanted patients dying within 2 months of steroid non-response. Among the transplant recipients who died, five of six succumbed to infectious complications within two weeks of surgery.

Figure 3: Kaplan–Meier Estimates of Survival in the 26 Study Patients and the 26 Best-Fit Matched Controls. Philippe Mathurin et al. Early Liver Transplantation for Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1790-1800. Figure from: (https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1105703)

Importantly, the study found no survival difference between patients who responded to steroids and those who received transplants, suggesting that medical management remains appropriate for steroid-responsive patients. Regarding alcohol recidivism—a central concern in this patient population—no transplant recipients returned to drinking at 1 and 6 months post-transplant. After approximately two years, only three patients had resumed alcohol consumption, with one drinking occasionally and two drinking daily. Notably, none of these patients experienced graft dysfunction. This relapse rate was substantially lower than the 30% previously estimated for patients who bypassed the 6-month abstinence rule.

These findings have since been corroborated by additional research, including studies from the American Consortium for Early Liver Transplantation (ACCELERATE-AH), which demonstrated similar 3-year survival rates for early liver transplant recipients compared to historical controls who completed the mandatory abstinence period before transplantation.

How This Changed Our Approach to Transplantation

After this groundbreaking study was published, pilot programs in academic centers began to trial early transplantation protocols. As these centers continued to observe positive outcomes and success, transplantation for both alcohol-associated hepatitis and alcohol-associated liver disease increased substantially and spread throughout the United States.

Figure 4: Trends in deceased-donor liver transplantation by United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) region for candidates diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis in the U.S. Figure from: Thomas Cotter et al. Liver transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis in the United States: Excellent outcomes with profound temporal and geographic variation in frequency. Am J Transplant. 2021 Mar;21(3):1039-1055. (https://www.amjtransplant.org/article/S1600-6135(22)08440-4/fulltext)

Transplants for alcohol-associated hepatitis increased dramatically from less than 1% of all liver transplants pre-2011 to approximately 15% by 2020.

This paradigm shift had a profound impact on liver transplantation volumes across the United States. Following the publication of the Mathurin study, transplant for alcohol hepatitis increased 5-fold, from 2014 to 2019. While ALD accounted for only 12-19% of transplants before 2011, it now represents approximately 40% of all liver transplants nationwide. In absolute numbers, the change is equally striking—from just 805 ALD-related transplants performed in 2011 to 2,534 by 2023. This more than threefold increase reflects both the growing prevalence of alcohol-associated liver disease and the widespread adoption of new transplantation policies that no longer rigidly enforce the 6-month abstinence rule for carefully selected patients.

What Do Rates of Return to Drinking Look Like in This Era?

For ALD transplant recipients, alcohol relapse occurs at a rate of 4.7% per year for any alcohol use and 2.9% per year for heavy alcohol consumption.

In a study of early liver transplantation for patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis, researchers identified 146 patients exhibiting four possible patterns of drinking behavior:

- 103 patients (70.5%) remained completely abstinent

- 9 patients (6.2%) experienced late relapse (after 1 year) with non-frequent drinking (<4 days per week) and non-binge drinking (<5 drinks at a time)

- 22 patients (15.1%) developed early-onset (within 1 year) sustained non-frequent and non-binge alcohol use

- 12 patients (8.2%) exhibited early-onset sustained binge drinking (>5 drinks at a time) or frequent alcohol use (>4 days per week)

Figure 5: Patterns of posttransplant alcohol use. Figure from: Brian Lee et al. Patterns of Alcohol Use After Early Liver Transplantation for Alcoholic Hepatitis. (https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(20)31558-5/fulltext#fig1)

The patterns that appear most significant for outcomes are heavy alcohol consumption and early return to drinking, even when consumption is light. This evidence suggests that rather than treating alcohol use as a monolithic behavior, clinical approaches should focus specifically on preventing early resumption of drinking and heavy consumption patterns.

Figure 6: Average life expectancy after early LT by pattern of posttransplant alcohol use. Estimated probability of 20-year post-LT survival by pattern of posttransplant alcohol use. Figure from: Brian Lee et al. Patterns of Alcohol Use After Early Liver Transplantation for Alcoholic Hepatitis. https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(20)31558-5/fulltext#fig3

What Does Psychosocial Evaluation Look Like Now That We Don't Use the 6-Month Rule?

Several factors have been identified that predict relapse post-transplant:

- History of multiple rehabilitation attempts/relapses

- Younger age at presentation

- High daily alcohol consumption (>10 drinks daily)

- Limited duration of abstinence (while not the sole factor, it remains relevant)

- Untreated psychological or psychiatric conditions

- History of polysubstance use

- History of legal consequences related to substance use

- Reluctance to engage in AUD treatment

- Inadequate social support network

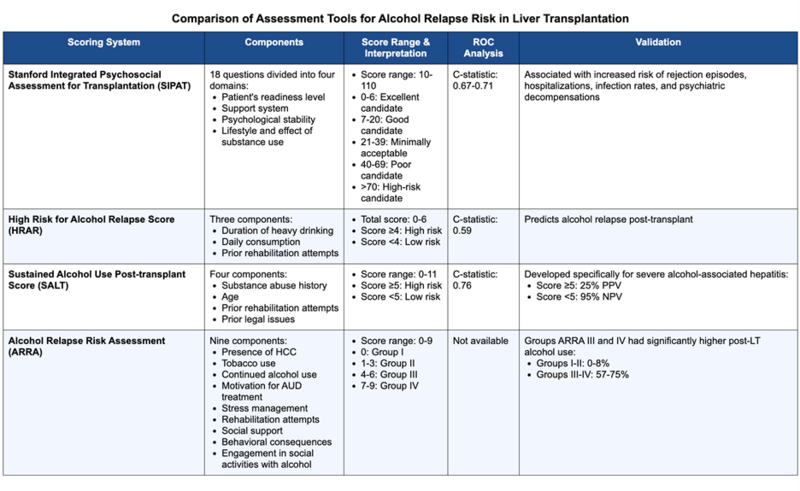

To systematically apply these factors, multiple validated tools are now available for standardized assessment of alcohol use risk:

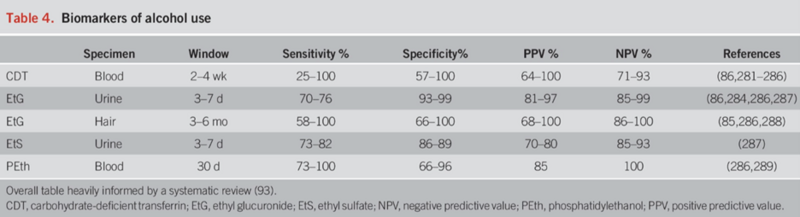

Improved biochemical/serologic tests are now available to complement psychosocial assessment. Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) can detect alcohol metabolites in whole blood up to a month after consumption.

Figure 7: Table of biomarker of alcohol use. Figure from Loretta Jophlin et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Sep 1;119(1):30–54.(https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2024/01000/acg_clinical_guideline__alcohol_associated_liver.13.aspx)

Perhaps most importantly, comprehensive assessment should be conducted on an ongoing basis through a multidisciplinary approach involving addiction medicine specialists, psychiatrists, social workers, and family members.

The Future of Alcohol-Associated Liver Transplantation

The evolution away from the rigid 6-month rule represents just the beginning of a broader paradigm shift in alcohol-associated liver transplantation. Looking forward, several developments will likely shape the field:

- Precision medicine approaches will refine patient selection through biomarkers, genetic risk profiling and more sophisticated psychosocial assessment tools, enabling clinicians to better predict outcomes.

- Increased integration of addiction medicine into transplant programs will continue to expand, with dedicated specialists embedded within transplant teams to provide comprehensive care throughout the transplant journey. Early evidence suggests this approach significantly reduces relapse rates and improves overall outcomes.

- Enhanced pharmacotherapy for AUD (see prior why series), when combined with behavioral interventions, shows promise in supporting long-term abstinence post-transplant. Medications like naltrexone, and acamprosate have been studied and validated in this population. Additionally agents such as GLP-1 receptor agonists are emerging as new tools for AUD management.

- Technological innovations such as digital monitoring tools, transdermal alcohol sensors and mobile health applications may provide real-time support for patients, enabling earlier intervention before relapse progresses to harmful drinking patterns.

- Addressing health disparities has become increasingly central to transplant programs, with targeted efforts to ensure equitable access across racial, socioeconomic, and geographic boundaries. Improvements have already been made to increase transplant access for women and underrepresented ethnic minorities

- Continued outreach and advocacy by transplant programs will further destigmatize alcohol-associated liver disease and potentially increase organ donation rates specifically for these patients.

As transplant programs continue to refine their approaches based on accumulating evidence, the focus is shifting from simply whether to transplant patients with alcohol-associated liver disease to how best to support these individuals throughout their recovery journey and post-transplant lives. The field stands at an inflection point, with the opportunity to develop truly comprehensive models of care that address both the hepatic manifestations of disease and the underlying substance use disorder with equal rigor and compassion.

Key Takeaway Points

- Alcohol-associated liver disease is increasing in prevalence and is currently the leading indication for liver transplantation.

- Historically, liver transplantation was rarely performed for patients with ALD.

- The 6-month sobriety rule was widely adopted by transplant programs throughout the United States but proved problematic due to its poor correlation with post-transplant sobriety, documented disparities affecting Black patients and women, and inconsistent application across centers.

- The landmark Mathurin study demonstrated that carefully selected patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis can successfully undergo transplantation without meeting the traditional 6-month abstinence requirement.

- Following this paradigm shift, ALD transplants have increased steadily, fundamentally changing the landscape of liver transplantation.

- The preferred approach to pre-transplant assessment now includes validated psychometric tools, objective biomarkers such as PEth, and a comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation model.

- The future of ALD transplant will involve more individualized risk assessment and greater integration of AUD disorder into post-transplant care.