Why are GLP-1 agonists being used to treat patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease?

GLP-1 agonists are approved for the treatment of diabetes and for obesity. Why are patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) suddenly being prescribed GLP-1 agonists and what are the effects on the liver? To tackle these questions, let’s start with some disease definitions…

What is NAFLD?

NAFLD is a basic umbrella term to describe the entire spectrum of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. This includes hepatic steatosis, where 5% or more hepatocytes have macrovesicular steatosis in the absence of other causes of macrovascular steatosis in individuals who drink little or no alcohol, which is defined as less than 20 g/day for women and less than 30 g/day for men. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis or NASH is defined as macrovesicular steatosis with inflammatory changes and cellular injury with hepatocellular ballooning, with or without fibrosis. NASH can progress to cirrhosis, which is characterized by the formation of fibrous bands and regenerative nodules throughout the liver.

Who is at risk of NAFLD?

It is estimated that approximately 1 in 4 people in the world have NAFLD. Of these individuals, up to 15% of have NASH. There is a strong association between NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome with higher risk of NASH in those with underlying diabetes or obesity. Individuals with diabetes are at particularly high risk of NAFLD, theorized to be due to excess energy driving insulin resistance seen in diabetes resulting in increased uptake of free fatty acids in the liver. This results in hepatic steatosis, which can cause inflammation over time.

What medical comorbidities are associated with NAFLD?

Medical conditions associated with the metabolic syndrome such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and hyperlipidemia are all associated with NAFLD. It is estimated that as many as half of diabetics have underlying NAFLD, with a higher risk of progression to NASH with fibrosis than non-diabetics. It is currently recommended that all patients with diabetes be screened for advanced fibrosis every 1-2 years. Conversely, given the strong association between NAFLD and diabetes, it is also recommended that all people with NAFLD be screened for diabetes. First degree relatives of individuals with NASH cirrhosis are also recommended to be screened for advanced fibrosis. Obesity, particularly in those with android body fat distribution, are at increased risk of NAFLD and disease progression and individuals with complications such as hypertension, knee osteoarthritis, or sleep apnea should also be screened for advanced liver disease.

FIB-4 is recommended as an initial screening test for advanced fibrosis and is calculated using readily available patient information that includes age, AST, ALT, and platelet count. FIB-4 has both good negative and positive predictive value for advanced fibrosis. It is proposed that this non-invasive risk score be used in a primary care clinic and non-hepatology settings to identify individuals at high risk of advanced liver disease with FIB-4 scores greater than 2.67 and refer them to hepatology. If FIB-4 score falls into an intermediate category where score is greater than 1.3, which is the threshold used to rule out advanced fibrosis, but less than 2.67, secondary assessment is needed. Vibration controlled transient elastography (VCTE) is most commonly used methods to assess for fibrosis, with liver stiffness measurements less than 8 kPa used to rule out advanced fibrosis. Any score greater than 8 kPA on VCTE should be referred to Hepatology for further assessment.

MR elastography is considered the most accurate noninvasive modality and can be helpful in cases of clinical uncertainty and to confirm advanced fibrosis. Liver biopsy is considered the gold standard to assess and stage fibrosis but are generally reserved for cases where diagnostic uncertainty exists, given that liver biopsies are invasive and carry the rare but real risk of life-threatening complications.

What treatments exist for NAFLD?

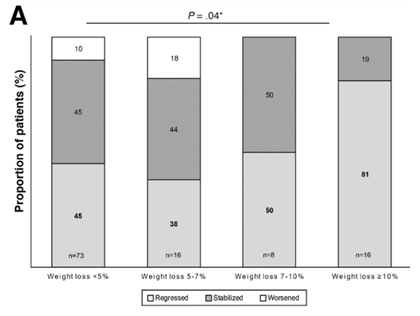

The best studied and current cornerstone of treatment for NAFLD is weight loss. In one prospective study, greater than 10% weight loss led to regression in liver fibrosis with greater than 5% weight loss reducing hepatic steatosis. The degree of weight loss was independently associated with statistically significant improvements in all NASH-related histologic parameters and provides strong evidence that weight loss is an effective treatment for NAFLD.

The problem is that weight loss is notoriously difficult to achieve particularly with lifestyle modifications, such as diet and exercise, alone. One study demonstrated that less than a third individuals achieved greater than 5% weight loss during the three-year study period and only 25% of these individuals were able to maintain greater than 5% weight loss.

Despite these limitations, current guidance recommends a diet that leads to a caloric deficit. A diet with limited carbohydrates and saturated fat and enriched with high fiber and unsaturated fats, such as the Mediterranean diet, should be encouraged due to the cardiovascular benefits that are seen. In a meta-analysis, the Mediterranean diet reduced patient’s alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (P < 0.001), hepatic steatosis (P = 0.02), and liver stiffness (P = 0.01) although the overall effect sizes were small.

There is also evidence that moderate exercise at least five times per week for a total of 150 min per week or an increase in activity level by more than 60 min per week improved liver enzymes and other metabolic indices. A consensus document put out by the American College of Sports Medicine suggests 75 minutes per week of vigorous intensity physical activity as an alternative exercise regimen.

What type of exercise, you ask? This study looked aerobic and resistance exercise regimens for people with NAFLD and found similar outcomes in reducing hepatic steatosis but lower total energy consumption in those who completed resistance exercise. Patients with advanced liver disease, who are already at increased risk of sarcopenia, may benefit from an exercise regimen that requires lower energy expenditure and may be better for patients who cannot tolerate aerobic exercise. Weight loss goals should be personalized to each patient and weighed against risks of contributing to sarcopenia. Exercise benefits extend beyond improvements in liver outcomes, and have been shown to provide cardiovascular benefits, which is important as cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death in this population.

Believe it or not, coffee has also been shown to reduce NAFLD. This meta-analysis showed that there was a dose dependent decreased risk of NAFLD occurrence that became statistically significant at three cups of coffee per day.

Given the difficulty with lifestyle changes such as diet, there is a need for alternative treatments for treating NAFLD. ENTER: GLP-1 agonists.

How do GLP-1 receptor agonists work?

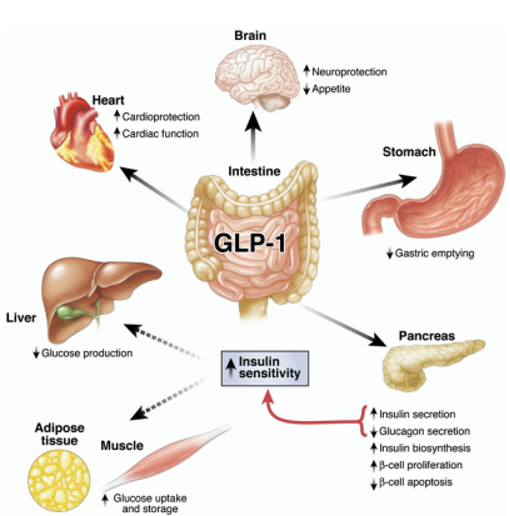

Glucagon-like peptide-1 or GLP-1 is native to the body and is released from the small intestine after a meal ingestion. It is thought to work by lowering blood glucose by inducing insulin secretion through incretin action and reducing glucagon secretion. It has also been shown to delay gastric emptying and help suppress appetite. However, GLP-1 is quickly degraded in the body leading to a short time of action. Synthetic GLP-1 receptor agonists are long acting with a 13 hour half-life and have been shown to improve glycemic control and aid in weight loss.

What are the cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1 agonists?

GLP-1 agonists have clear cardiovascular benefits. A large systemic review of cardiovascular outcomes of people taking GLP-1 agonists significantly reduces death from cardiovascular causes by 12% and stroke by 16%. The decrease in cardiovascular events may be related to the effect on reducing blood pressure, or through lowering triglycerides and total cholesterol. Additional studies have also shown that patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists also have significantly lower rates of kidney outcomes such as macroalbuminuria or progression to end-stage kidney disease.

Do GLP-1 agonists help with weight loss?

Liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide are all GLP-1 agonists resulting in significant weight loss in RCTs. Liraglutide has shown significant weight loss compared with placebo with the majority of participants achieving more than 5% total body weight loss during the follow up period and 33% (vs 10%) achieving 10% total body weight loss or greater.

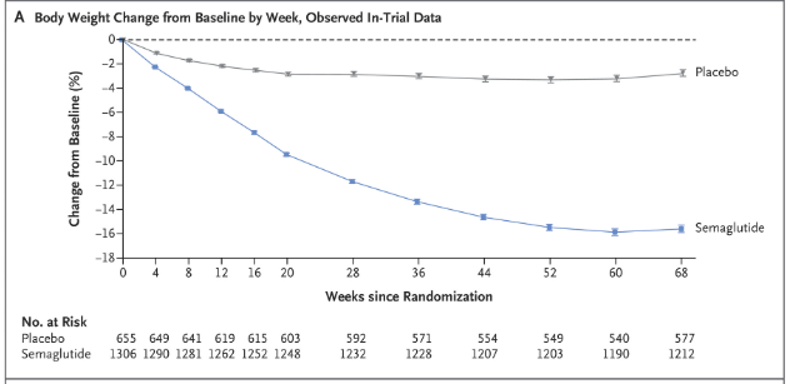

In the landmark study for semaglutide, participants were randomized to semaglutide or placebo plus lifestyle interventions. Participants in the semglutide group achieved 14.9% total body weight loss as compared with 2.4% in the placebo group (p< 0.001). Notably, this weight loss was sustained throughout the 68 week study period.

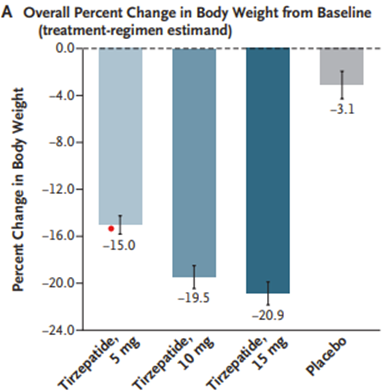

A newer GLP-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide, demonstrates weight loss as high as 20% change in body weight compared with 3% in the placebo group in a RCT. Weight loss was sustained throughout the study period and tirzepatide showed improvements in cardiometabolic endpoints such as fasting lipids and hypertension.

What are the side effects of GLP-1 agonists?

GLP-1 agonists are generally well tolerated with GI side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea predominating. Most side effects are dose dependent and can be transient. There is also increased risk of cholelithiasis although stone formation may be more related to the rapid weight loss seen while on the medication than the medication itself. Although there were some initial concerns, increased rates of pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer have not been seen in meta-analysis.

Why are GLP-1 agonists being used for NAFLD?

At the present moment, there are currently no FDA approved medications for NASH. However, GLP-1 receptor agonists have shown the most promise of all the classes of medications. AASLD guidance recommends considering them in patients with concurrent co-morbidities such as obesity and diabetes given their potential benefit in NAFLD.

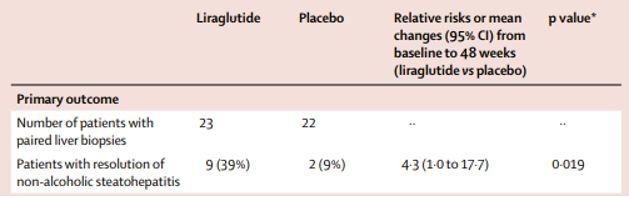

In the LEAN trial, Liraglutide was shown to have a higher rates of NASH resolution and lower rates of fibrosis progression compared to placebo. There was also lower rates of fibrosis progression in the liraglutide group as compared to placebo. Participants taking liraglutide also achieved a 5.5% total body weight change compared with placebo over the 48-week study period. This phase 2 study showed promising results, but the study was small and only included 52 participants.

In a larger NEJM randomized control trial, NASH resolution was dose dependent and occurred in 59% in the semaglutide group versus 17% in the placebo group (p < 0.001). An improvement in fibrosis stage was seen in 43% of the higher dose semaglutide group versus 33% of the patients in the placebo group but this was not statistically significant. Patients receiving semaglutide also achieved a whopping 12.5% reduction in their total body weight over the 72-week study period. Given the study did not show a significant difference in fibrosis stage, semaglutide has not yet been FDA approved for NASH.

Another phase 2 RCT studying semglutide 2.4 mg vs placebo in patients with compensated NASH cirrhosis did not show any statistically significant difference in NASH resolution or improvement in liver fibrosis between the groups. However, the study included a small number of participants and a shorter follow up time of only 48 weeks compared to other RCTs studying GLP-1 agonists. The study also showed several cardiometabolic benefits of semaglutide with significant improvement in hemoglobin A1C, body weight, and cholesterol reduction compared to placebo. Notably, there were no hepatic decompensations or increased side effects in the semaglutide group, suggesting that GLP-1 agonists are likely safe in compensated cirrhosis.

Tirzepatide has also shown some promising results with up to 8% absolute reduction in liver fat content in a RCT. Future studies are needed to determine if there is a benefit in NASH reduction or fibrosis regression.

Studies are lacking on the safety and efficacy of GLP-agonists in decompensated NASH cirrhosis. In a retrospective study GLP-1 agonists have been shown to be associated with lower rates of hepatic decompensations compared to other glycemic agents, although more prospective data is needed.

Why haven’t GLP-1 agonists been approved for NASH?

The FDA has set out specific clinical benchmarks for drug approval for NASH. Given the high disease burden of NASH and limited therapeutic options currently available, the FDA has proposed an accelerated pathway for drug approval. The proposed clinical trial endpoints are the resolution of steatohepatitis without worsening or liver fibrosis and/or improvement in liver fibrosis one stage or greater without worsening of steatohepatitis. The FDA also recommends examining hard clinical endpoints such hepatic decompensations, transplant free survival, and all-cause mortality, although these results are not necessarily needed prior to drug approval given the long length of follow up potentially required.

There are ongoing studies including a large phase 3 trial underway to determine if semaglutide will meet any of these clinical endpoints for FDA approval. There is a lot of excitement around GLP-1 agonists, and it is the hope that one will end up being approved for NASH in the near future. Stay tuned!