What is THAT on your liver?

What is a hepatocellular adenoma?

A hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) is a solid, benign epithelial liver lesion that develops in an otherwise normal liver. HCAs are most commonly found in the livers of young women (22-44 years-old) using estrogen-containing oral contraceptive pills. Other risk factors include alcohol use, obesity, metabolic syndrome, anabolic androgenic steroid use and glycogen storage diseases.

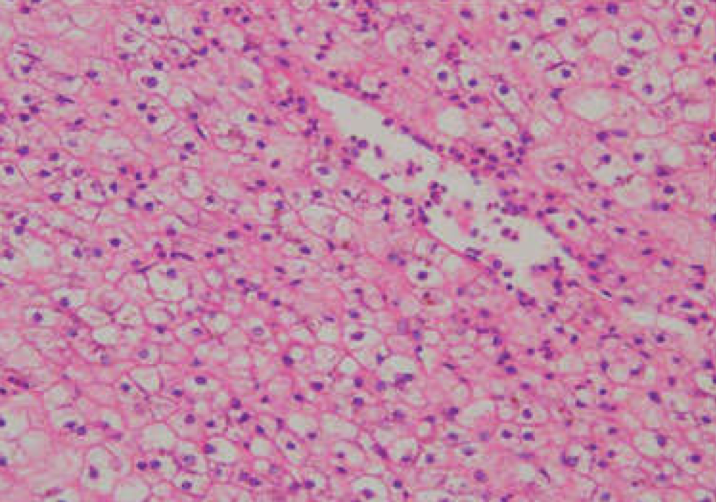

HCAs can vary in size from <1 to 30 cm. They more commonly occur in the right hepatic lobe and 70-80% of HCAs are solitary lesions. HCAs do not have a capsule. Microscopically, they are composed of large adenoma cells containing glycogen and lipid. The adenoma cells are arranged in plates and there is an absence of portal triads, which can histopathologically distinguish them from focal nodular hyperplasia. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 - Pathology of hepatocellular adenoma. Large adenoma cells arranged in plates with no evidence of portal triads.

Hepatocellular adenomas and OCP use

HCAs are rare, occurring in 1/1,000,000 non-OCP users. Prevalence increases to 30-40/1,000,000 in long-term OCP users. OCP users are more likely to have multiple HCAs that are larger in size and more likely to bleed. In one study, women over the age of 30 years-old using OCPs >25 months were found to be at highest risk for developing HCAs. There was a 500-fold increased risk in those using OCPs >85 months and a lower incidence in those using low-dose estrogen OCPs.

What are the clinical features?

Hepatocellular adenomas can be asymptomatic and incidentally discovered on imaging or present with life-threatening hemorrhagic shock. The most common presenting symptom is epigastric or right upper quadrant abdominal pain that may be the result of an enlarged liver, bleeding or necrosis (Figure 2). Physical exam may be normal or notable for hepatomegaly or a palpable abdominal mass.

Figure 2 - Relative frequency of hepatocellular adenoma presentation

Laboratory studies are most commonly normal but liver enzyme abnormalities can be seen in those with particularly large (>5 cm) lesions. The most common liver enzyme abnormality is an elevated alkaline phosphatase which may occur as a result of bleeding or bile duct compression.

CT and MRI can help differentiate HCAs from other liver lesions. On non-contrast CT scans HCAs are well-demarcated and can be isodense, low-attenuating or heterogenous. On contrast-enhanced, multiphase CT, HCAs demonstrate peripheral enhancement during the early (arterial) phase and centripetal flow during the portal venous phase. Lesions then become isodense during the late (venous) phase and hypodense on post-contrast phases. (Figure 3)

Figure 3 - CT scan of a hepatocellular adenoma on arterial phase (left) and portal venous phase (right).

Case courtesy of Associate Professor Natalie Yang, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 6951

HCAs are also well-demarcated on MRI due to fat and glycogen within the lesions. On contrast-enhanced MRI there is early arterial enhancement and lesions become isointense to the remainder of the liver on delayed images. With Eovist (hepatobiliary-specific contrast) adenomas appear hypointense on the hepatobiliary phase due to reduced uptake.

What are the complications from a hepatocellular adenoma?

The most concerning complications of HCAs are spontaneous hemorrhage and malignant transformation. The incidence of spontaneous hemorrhage is estimated to be 25-64% in symptomatic patients. Lesion size >5 cm, the use of OCPs and pregnancy increase the risk for spontaneous hemorrhage. Patients experiencing spontaneous hemorrhage most commonly present with acute onset severe abdominal pain. In rare cases, bleeding can lead to spontaneous lesion rupture and patients will present with hemodynamic instability and an acute abdomen secondary to hemoperitoneum (Figure 4).

Figure 4 - CT scan demonstrating a hepatocellular adenoma with spontaneous rupture.

Case courtesy of Dr Abdelmoniem Mahmoud, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 67367

Malignant transformation of an HCA to a carcinoma is less common, with an estimated incidence of 8-13%. The risk of malignant transformation varies by genotype-phenotype classification. HCAs with beta-catenin activation are the least common (10-15%) but carry the highest risk of malignant transformation. Inflammatory adenomas (50%) and those with hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)-1 alpha mutations (35-50%) have a significantly lower risk of malignant transformation. Additional risk factors include lesion size >5 cm and male sex. An increase is size of the lesion or an increase in serum alpha-fetal protein (AFP) level should raise suspicion for malignant transformation.

How do you manage a hepatocellular adenoma?

The management of HCAs is based on size and the presence of symptoms. Asymptomatic patients with lesions <5 cm should be encouraged to lose weight and their oral contraceptive pills should be discontinued. With these conservative measures alone, HCAs can significantly decrease in size. Surveillance with an MRI abdomen and serum AFP every 6 months should be considered to monitor for complications. If the lesion grows, bleeds or develops concerning features, intervention should strongly be considered.

In those patients presenting with symptoms or lesions >5 cm surgical options include enucleation, resection and liver transplantation. In the event of spontaneous hemorrhage, trans-arterial embolization should be pursued. Trans-arterial embolization can also be considered to reduce the size of an HCA prior to surgical intervention. Finally, if a lesion or lesions cannot be resected, radiofrequency ablation can also be considered.

Figure 5 - Management of hepatocellular adenomas

Women with HCAs of reproductive age should be counseled to avoid estrogen-containing OCPs as estrogens promote adenoma growth. Progestin-only contraceptive options are considered safe. Reproductive-aged women should also be counseled on the possibility of adenoma growth and rupture during pregnancy. For HCAs >5 cm embolization or resection can be considered prior to pregnancy to decrease risk.

For pregnant women with HCAs, surveillance imaging is recommended with a liver ultrasound every 6-12 weeks during pregnancy and postpartum. Surgical resection should be considered if lesions are growing, large (>5 cm), or symptomatic. Ideally resection should be performed during the 2ndtrimester to minimize risks to fetus and mother.