Impact of Climate Change on Patients with Liver Disease

Defining the Climate Crisis

2011-2020 was the warmest decade ever recorded. The global temperature is predicted to rise another 2.7°F by 2040 according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The main driver of climate change is greenhouse gases related to combustion of fossil fuels, according to the United Nations.

This change in temperature, or climate change, is associated with an increase in extreme weather events including massive flooding, heat waves, drought, wildfires, and storms. The resultant urgency to act to stem the results of climate change is often referred to as the Climate Crisis.

The healthcare community has already seen devastating mortality from severe weather events and massive but not fully recognized impacts on morbidity, and strain on the social and environmental determents of health. There is a concern that the changing climate is already impacting our patients with liver disease. It is important to understand the potential impact of climate change on our patients and consider what we can do to impact the resultant climate crisis.

Climate Change and the Prevalence of Chronic Liver Disease

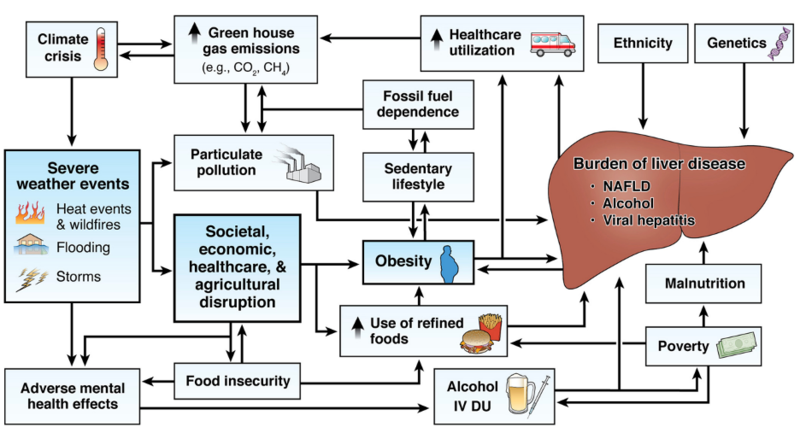

More common severe weather events increasingly lead to societal, economic and agricultural disruptions resulting in worsening food insecurity in vulnerable areas (Wheeler et al). This is predicted to worsen refined food use and increase obesity which in turn may increase the global burden of liver disease from MASLD (Fig. 1). Optimal nutrition is a cornerstone of management for liver disease, specifically for those with metabolic (dysfunction)-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). As discussed in my earlier posts, Malnutrition in the Adult with Cirrhosis and Food Security in the Adult with Liver Disease, malnutrition is common in patients with cirrhosis and is more common amongst those experiencing food insecurity. With worsening weather patterns, increased temperatures and increased air pollution there is also a concern for accompanying sedentary lifestyles with higher global temperatures, further increasing the prevalence of MASLD.

With increasing weather-related disasters, Ingle et al showed increasing mental distress both in affected countries and globally due to so called “eco-anxiety.” With increased temperatures, Parks et al showed higher rates of substance- and alcohol-related hospitalizations. The increased substance use and mental health burden in turn could result in more patients with alcohol and hepatitis related liver disease (Fig. 1). Notably, alcohol consumption is responsible for 3-11% of diet related greenhouse gas emissions due to high greenhouse gas use in production and distribution, resulting in a vicious cycle (Donnelly et al). Different foods and their environmental impact can be explored through the BBC food calculator.

Figure 1: From Donnelly et al, "The multifaceted relationship between climate change and liver disease."

Climate Change and Infectious Causes of Liver Disease

Many biological hepatotoxins thrive in warmer, wetter climates. Aflatoxin producing fungi prefer warm damp climates and can result in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver fluke outbreaks are becoming more common in the United Kingdom; there are now regular outbreaks moving up in latitude due to rain, temperature and agricultural pattern changes, according to Fox et al. Recent outbreaks of schistosomiasis in more northern climates have been unexpected and are thought to be related to climate change, according to Donnelly et al. Waterborne infections including hepatitis A and hepatitis E may also increase with rising global temperatures due to rising flood rates and mass migration due to displacement.

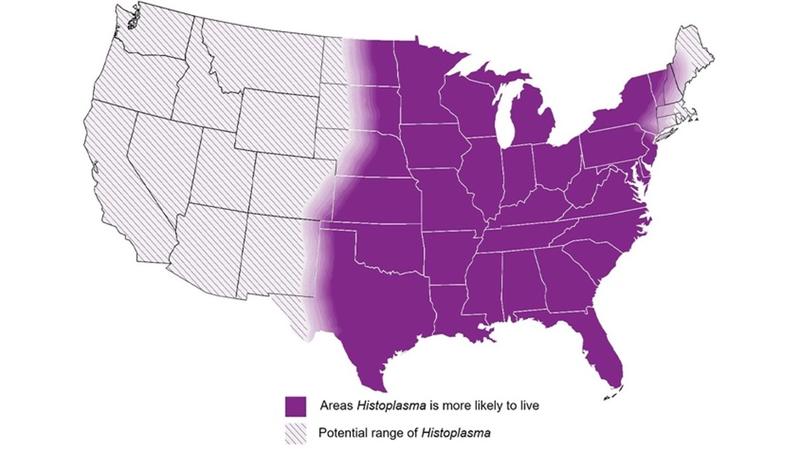

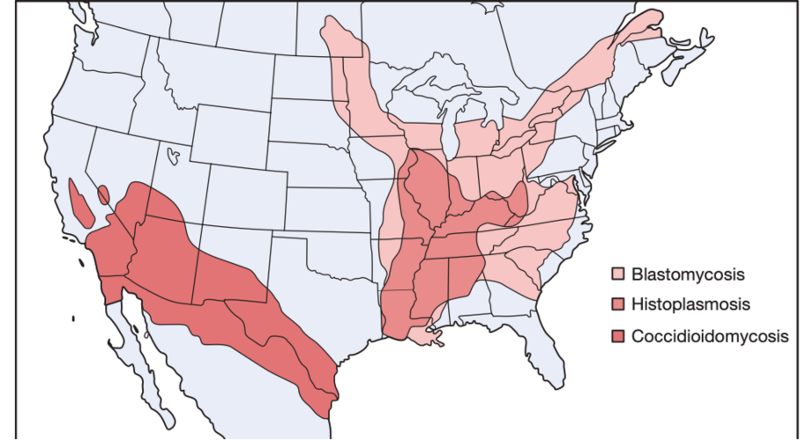

Our immunocompromised patients are at higher risk for zoonotic diseases, which are rising in prevalence due to habitat and agricultural changes, like H5N1, according to Phillips et al. Fungal diseases are increasing in prevalence as fungi adapt to rising global temperatures (thermo-adaptation), now more able to survive within the human host. This has resulted in new species of fungi that are pathogenic to humans, like Candida auris. Endemic mycoses have expanded in location across the United States, well outside of the borders previously taught in medical school (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: CDC map of current histoplasmosis distribution in purple above traditional (but now outdated) First Aid for the USMLE Step 2 CK 2016 with histoplasmosis confined to the Ohio River Valley.

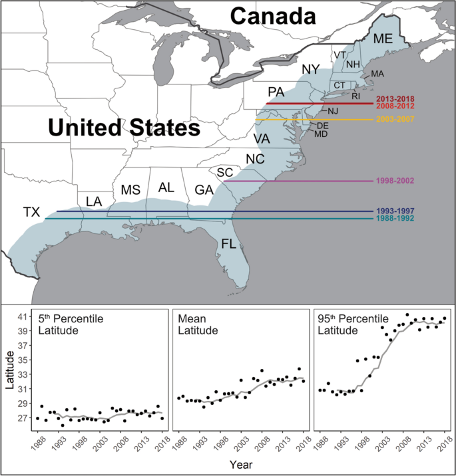

One of the deadliest examples of climate change-related illness in our patients with liver disease is the rise of Vibrio vulnificus infections. While this is a low incidence human pathogen, it has a high fatality rate of 18-50%. As outlined by Archer et al, analysis of a 30 year database of V. vulnificus infections showed cases rising along with Atlantic coastline and extending northward in a non-linear progression (Fig. 3). V. vulnificus can be found in brackish water. Patients with cirrhosis should avoid eating raw seafood (especially oysters) and exposing any open wounds to brackish water.

Figure 3: Latitudinal shifts by year of confirmed non-foodborne V. vulnificus infections in the U.S. by Archer et al.

Impact of the Hepatologist on Climate Change

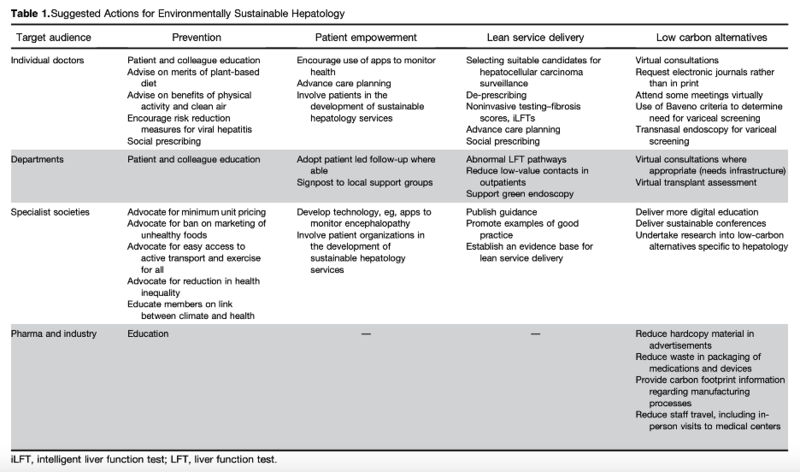

Healthcare is responsible for about 5% of the global carbon footprint (Haddock et al). Gastroenterology procedures are the third highest generator of water in a hospital system. There are calls for increased attention to this problem and associated creative solutions to minimize our impact in hepatology by Donnelly et al. Some suggested individual, departmental, society based, and industry-based changes are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Suggested Actions for Environmentally Sustainable Hepatology from Donnelly et al.

While reducing low-value health care contacts by converting appointments to virtual visits when able, promoting green-endoscopy, and virtually attending conferences may help, larger scale interventions and research are needed. We need to better understand these climate change related risks for our patients and our practice to best understand how to optimize their care now, and at the even warmer temperatures to come.

Teaching Points:

- Climate change may impact multiple causes of liver disease.

- Due to global temperature changes, the geographic infectious disease burden is changing.

- Hepatologists can decrease their environmental impact through individual, group, and societal action.