How Do I Manage Alcohol Use Disorder in Hepatology Clinic?

Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder

Many patients who present to hepatology clinic for treatment of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) already have an established diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD). However, some cases may be equivocal, such as a case of underlying NAFLD with regular alcohol use. In these situations, screening tools can be helpful. One of the most commonly used screening tools for AUD is the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C), which is comprised of 3 questions. It is adapted from the 10-item full AUDIT, and is more efficient than the 10-item AUDIT with similar overall performance, though has lower specificity. The 10-item AUDIT or the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) are longer tests for AUD screening, but may be used to gather more detailed information. It is important to note that the AUDIT-C has much better sensitivity than specificity, so a positive screen does not indicate alcohol use disorder, and thus requires further evaluation to determine if a use disorder is present.

Once a patient has screened positive for a possible AUD, a formal diagnosis should be made using DSM-V criteria. The diagnoses of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence from the DSM-IV were replaced with the new DSM-V classification, now as a combined diagnosis of “Alcohol Use Disorder”. It is comprised of 11 criteria, and patients are categorized as mild (2-3 criteria), moderate (4 to 5), or severe (6 or more).

Table 1. DSM-V Criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder

Table from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-use-disorder-comparison-between-dsm

Biochemical Assessment:

Alcohol biomarkers can be useful in the management of AUD because they can detect early slips or relapses and assess treatment effectiveness. Biochemical assessment can include urine ethylglucuronide (EtG) and ethyl sulfate (EtS), carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT), or phosphatidylethanol (PEth). Urine EtG and EtS measure byproducts of ethanol metabolism and can be detected in the urine for up to 48-72 ours. Urine EtG has been studied in the pre-transplant setting and can detect alcohol use that was not uncovered through self-report, serum testing, or breath alcohol tests. The sensitivity and specificity for urine EtG is around 76% and 93% and EtS is 82% and 86%. PEth is a serum test and has a much longer detection window depending on the chronicity and amount of consumption. It can detect alcohol consumption up to around 3 weeks prior and has a sensitivity of close to 100% in heavier consumption. One concern about PEth, however, is that the results can be influenced by blood transfusions, as PEth can be stable for very long periods of time, particularly at colder temperatures, however this has not been demonstrated in any studies to date. CDT is not used as frequently due to poorer sensitivity. Furthermore, CDT is impacted by liver dysfunction and false positives have been noted in patients with chronic liver disease. As such, it is generally not recommended for patients with advanced liver disease. Serum ethanol, urine ethanol, and alcohol breath tests are helpful for acute intoxication, but their detection window is narrow and less helpful in the outpatient setting.

Table 2. Alcohol Biomarkers Used in Outpatient Clinical Practice

Psychosocial Interventions

Multiple psychosocial interventions are available for the treatment of AUD. Direct comparisons between approaches are challenging given heterogenous protocols and outcomes in the literature. However, several evidence-based approaches should be considered. In patients who have resistance to change or lack of motivation, structured motivational interviewing may be more helpful. Cognitive behavioral therapy offers structured, goal-directed therapy and has been successful across a wide range of substance use disorders, including AUD. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy may be helpful in in patients with co-occurring anxiety and depression because it is an evidence-based treatment for mood disorders. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) can be helpful for patients, and is free and readily available. Although some studies support its efficacy, it is decentralized and AA program quality can vary. Contingency management offers incentives to patients to maintain abstinence and has been effective in the treatment of AUD, but is not widely available in the outpatient setting. Residential treatment should be considered for patients with unstable housing, challenging home environments, or those who have failed all attempts at outpatient management, but to date no well-designed trials have assessed its effectiveness.

Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder

The majority of the evidence base for medical treatment of AUD is derived from studies of patients without known underlying liver disease. As such, the safety profile and pharmacodynamics of some of these medications are not well-understood in patients with cirrhosis.

Baclofen:

Baclofen is a GABAB agonist and although not FDA-approved for the treatment of AUD, is the most well-studied medication for treating AUD in patients with ALD. Since the first randomized trial was published in 2007, which demonstrated significant improvement in alcohol abstinence in patients with cirrhosis, other studies have supported its use.

Baclofen has been studied in both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis and has not been associated with any significant hepatotoxicity. Overall, evidence for baclofen in treating AUD has been mixed. The first randomized trial, published in the Lancet in 2007, demonstrated a remarkable improvement in abstinence in the treatment group (71%) compared to the placebo group (29%), p=0.0001. Two subsequent RCTs have been published with conflicting results. The first examined two doses of baclofen (30mg daily and 75mg daily) compared to placebo and demonstrated improvement in total abstinence days and time to relapse in the baclofen groups compared to placebo, with no differences noted between dosages, aside from more side effects reported in the higher dose. The largest RCT to date was performed in 180 patients with HCV/ALD and AUD but not cirrhosis, and demonstrated no significant difference between treatment and placebo groups.

Patients are typically started on 10mg three times daily and sometimes up-titrated to effect/as tolerated. In cirrhosis, it is rare to use doses greater than 75-90mg daily due to increased risk of side effects without clear benefit in AUD outcomes. The main side effects reported are fatigue, sedation, and dry mouth.

Acamprosate:

Acamprosate is an FDA-approved medication for treatment of AUD. Although renally metabolized with no known hepatoxicity, this medication had not been formally studied in patients with ALD or cirrhosis until 2021, when Tyson et al performed a retrospective cohort study of patients with cirrhosis who were prescribed baclofen or acamprosate for AUD. No significant differences in side effects or abstinence were observed, although patients with acamprosate had fewer hospitalizations.

Aside from the aforementioned study by Tyson et al, which was a small retrospective study, acamprosate has not been formally studied for AUD in ALD. The evidence supporting use of acamprosate for AUD comes is derived from data in patients without known underlying liver disease. The number needed to treat for the outcome of abstinence is 12 based on a large, well-designed systematic review and meta-analysis. Acamprosate is generally thought to be safe in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis with normal renal function, as it is renally excreted. LiverTox assigns acamprosate a “likelihood E” for risk of hepatoxicity, which is the lowest risk score given by LiverTox. To date, there have yet to be any published reports of clinically apparently liver injury due to acamprosate.

Acamprosate is dosed at 666mg three times daily, and is contraindicated if a patient’s GFR < 30. Patients with a stable GFR of 30-50 can be prescribed acamprosate at 333mg three times daily. The main side effects are diarrhea and worsening mood symptoms. Patients with a history of severe psychiatric disorders, depression, or suicidal ideation should be referred to addiction psychiatry for further evaluation and co-management.

Disulfiram:

Disulfiram, an acetyl-aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor, is an FDA-approved medication for AUD, however its use has been limited due to low adherence in patients. It is associated with significant drug-induced liver injury and should not be used if AST/ALT > 3 times the upper limit of normal or total bilirubin > 3. Disulfiram has not been studied in the setting of chronic liver disease and given the potential for significant hepatotoxicity and overall poor adherence, providers should maintain caution with any patient who has underlying liver disease and consider safer and better-studied alternatives.

Naltrexone:

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist and is one of the most effective medications available for the treatment of AUD. Currently no studies have assessed the use of naltrexone for AUD in patients with cirrhosis. Naltrexone is hepatically metabolized, and the pharmacodynamics are impacted in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. One study by Mitchell et al examined injectable naltrexone in patients with active HCV, and observed no hepatotoxicity or adverse effects, but they did not include patients with cirrhosis. Although naltrexone previously contained a black-box warning for patients with liver disease, this was removed given insufficient evidence of liver injury. In fact, no known cases of clinically apparent liver disease have been observed from naltrexone therapy, though LiverTox does indicate that hepatotoxicity has been suspected. While not studied in the AUD population, naltrexone has been studied in patients with cirrhosis and cholestatic pruritis. These studies have been short term (1-4 weeks), however no hepatotoxicity or adverse effects were observed.

Naltrexone has not been studied for AUD in patients with either compensated or decompensated cirrhosis. While the aforementioned studies examining cholestatic pruritis above included patients with cirrhosis, the longest study duration was 4 weeks, which is much shorter than naltrexone therapy for AUD. In general, it is considered acceptable to use naltrexone in patients with compensated cirrhosis with close monitoring, but should be avoided in Child-Pugh class C patients. It is thought that injectable naltrexone (which is a monthly, long-acting injection), may be safer due to bypass of first-pass metabolism, but this medication has also not been studied in patients with cirrhosis.

Naltrexone is a daily oral medication and dosed at 50mg per day, however some clinicians may start at a lower dose (25mg daily) in patients with cirrhosis because it is hepatically metabolized. The main side effects include diarrhea, nausea, and worsening mood symptoms. Patients with a history of severe psychiatric disorders, depression, or suicidal ideation should be referred to addiction psychiatry for further evaluation and co-management. Because naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist, it cannot be used in patients who are on chronic opioids, buprenorphine, or methadone, as this will precipitate opioid withdrawal in these patients.

Gabapentin:

Gabapentin is structurally similar to GABA and binds to voltage-gated calcium channels in the brain. Although FDA-approved for the treatment of epilepsy and neuropathic pain, doses of 300-600mg TID have also demonstrated benefit in AUD. However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that gabapentin only demonstrated a significant benefit in reduction of heavy drinking days and not in measures of abstinence or relapse.

Gabapentin has not specifically been studied for AUD in ALD patients, however is thought to be safe in both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. One small RCT has examined gabapentin for treating cholestatic pruritis in patients with cirrhosis (but not decompensated disease), and no hepatoxicity was noted.

Gabapentin is an oral medication, and generally started at 300mg TID, and can be up-titrated as tolerated/needed to 600mg TID. It can sometimes be added on top of medications like naltrexone, acamprosate, or baclofen to augment anti-craving effects as needed. No dose adjustments are recommended for hepatic dysfunction, and hepatotoxicity is rare. Gabapentin should be dose-reduced in the setting of renal dysfunction if the GFR is < 60. The main side effects reported are sleepiness and headache.

Topiramate:

Topiramate is FDA-approved for the treatment of seizures, and increases GABA activity and inhibits glutamate activity in the brain. It is generally considered for the treatment of AUD when first-line agents (naltrexone and acamprosate) aren’t tolerated or are unsuccessful. In a meta-analysis, topiramate treatment was associated with higher rates of abstinence and lower prevalence of heavy drinking.

Topiramate has not been studied in cirrhosis, but is hepatically metabolized (by CYP3A4). Hepatotoxicity is rare, and most cases have been linked to co-administration of other anti-convulsant, particularly valproic acid.

For AUD treatment, topiramate is typically dosed started at 25mg daily and slowly up-titrated (over at least 8 weeks) as tolerated/needed to 300mg daily divided into two doses. No dose adjustments are recommended for hepatic dysfunction, however due to its hepatic metabolism, starting at a lower dose with monitoring of side effects and slow-titration may be helpful for patients with more advanced liver disease.

Varenicline:

Varenicline is a partial nicotinic receptor agonist, and has been highly successful for tobacco cessation. A systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that varenicline is associated with subjective improvement in alcohol craving, but overall has not been associated with improvement in the alcohol outcomes of abstinence, relapse, and heavy drinking days. However, varenicline used for co-treatment of alcohol use disorder and tobacco use demonstrated significant improvements in both tobacco and alcohol abstinence. Therefore, if a patient with ALD is interested in smoking and alcohol co-treatment, varenicline should be considered. If alcohol cravings are sub-optimal, other medications can be added later.

Varenicline has not been studied in cirrhosis, however no dose adjustment is recommended in hepatic impairment. Hepatotoxicity is rare, and limited to mild episodes of hepatitis. Dosing for varenicline should be initiated approximately one week before a patient’s desired smoking cessation date, at 0.5mg daily for three days, then 0.5mg BID for three days, and then 1mg BID after that.

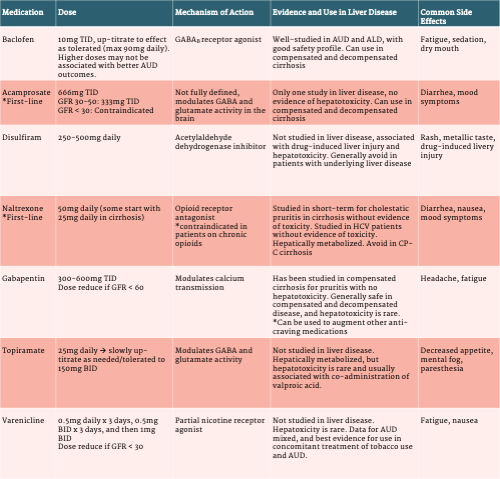

Table 3. Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder in Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease