Anticoagulant Doses for this Thrombosis

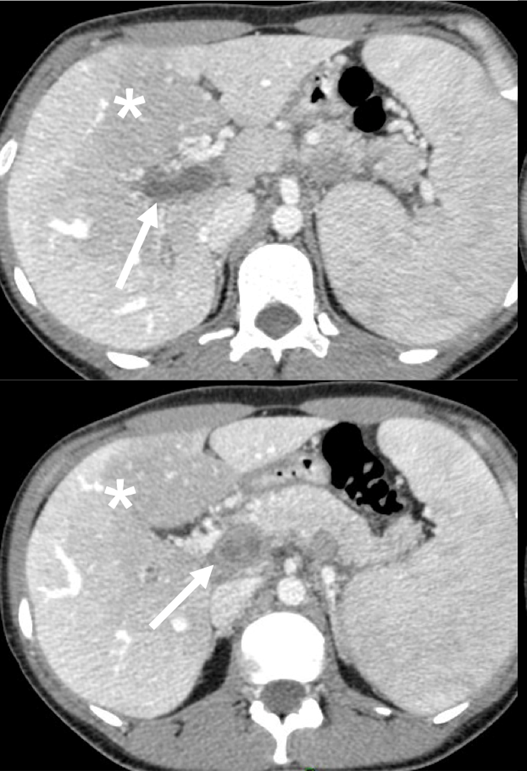

Contrast-enhanced image of an acute portal vein thrombosis in a patient without cirrhosis. The asterisk denotes an area of heterogeneous enhancement due to altered perfusion and the arrow outlines the expanded, non-enhanced portal vein consistent with thrombosis.

Adapted from Elkrief et al.

Hepatology is consulted!

Epidemiology of Portal Venous Thrombosis in Patients without Cirrhosis

Portal venous thrombosis (PVT) in patients without cirrhosis, or non-cirrhotic PVTs, often have an identifiable cause for increased thrombosis risk, either due to local or systemic factors. It is rare, with a prevalence that is likely <0.05%. These thromboses rarely resolve without anticoagulation.

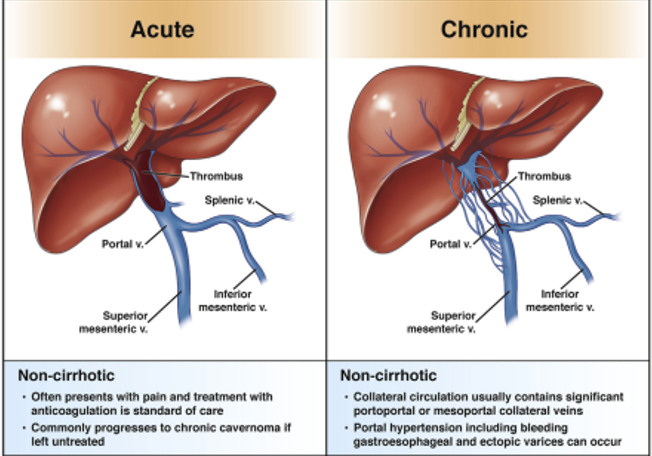

Figure 1. Acute and Chronic Non-Cirrhotic PVT

Adapted from Intagliata et al.

Practical Tips:

Think about the following categories for a rough outline on the etiology of Non-Cirrhotic PVT.

- Local factors and other general/iatrogenic risk factors

- Myeloproliferative neoplasm

- Inherited/Acquired Thrombophilia

- Systemic Diseases

- Idiopathic

Local Factors

Local or iatrogenic factors that have been implicated in the development of non-cirrhotic PVTs include obesity, hepatic surgery, blunt abdominal trauma, or solid-organ malignancy (extrahepatic).

Myeloproliferative Neoplasm

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are frequently found in patients with non-cirrhotic portal vein thrombosis. These neoplasms are found in 20-30% of non-cirrhotic PVT cases as PVT can oftentimes be the presenting symptom. These disorders are due to increase myeloproliferation or overproduction of matured blood cells. Some examples include essential thrombocythemia, idiopathic myelofibrosis, and polycythemia vera. In patients presenting with non-cirrhotic PVT, screening for MPN is necessary. Identification of the JAK2V617F mutation is helpful as it is present in nearly 50% of cases of essential thrombocythemia and idiopathic myelofibrosis, and nearly all patients with polycythemia vera.

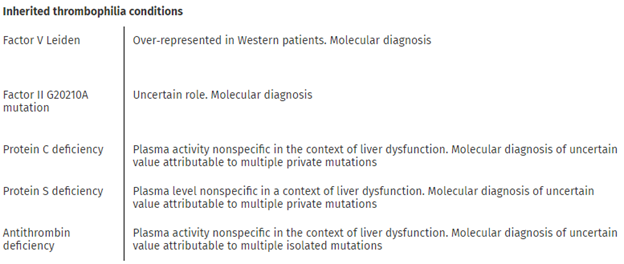

Inherited/Acquired Thrombophilia

Below are a few inherited thrombophilic conditions that place patients at higher risk of non-cirrhotic PVT.

Adapted from AASLD Vascular Liver Disorders Guideline

In addition to inherited thrombophilic conditions as above, other hematological disorders such as antiphospholipid syndrome and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria are less frequent but possible etiologies.

Systemic diseases that have been implicated in the development of non-cirrhotic PVTs, include malignancy, obesity, and inflammatory bowel disease including Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative Colitis.

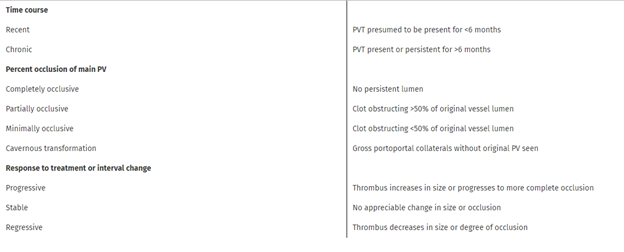

PVT Nomenclature

- Time Course

- Percent Occlusion of Main PV

- Extent (eg: involvement of main PV, branch PV, Confluence, splenic bein, or SM).

- Response to Treatment or Interval Change

Adapted from AASLD Vascular Liver Disorders Guideline

Myeloproliferative neoplasm screen:

JAK2V617F mutation – not detected

Thrombophilia screen:

Factor V Leiden G1691A mutation - not detected

Prothrombin G20210A mutation - not detected

Protein C normal

Protein S normal

Lupus anticoagulant - Anticardiolipin Ab positive, Anti-beta2 Glycoprotein I Ab positive by ELISA

PT - normal

PTT - normal

With the above work-up, our patient was diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome. As a reminder, this is a systemic autoimmune disease defined by thrombotic or obstetrical events that occur in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Pathogenesis involves an activation of inflammatory cells, promotion of coagulation and vasculopathy, and subsequent thrombosis. Patients may have concurrent nephropathy, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, or cognitive dysfunction. Notably, our patient’s platelet count was mildly depressed.

Management

- Prevent propagation

- Promote Recanalization

In general, unless patients are at high risk of bleeding, patients with PVT without cirrhosis should be placed on anticoagulation to avoid intestinal ischemia and prevent development of chronic PVT and consequences of portal hypertension.

Acutely life-threatening complications of PVTs include mesenteric ischemia from extension of clot burden into the mesenteric veins. If patients present with an acute abdomen (i.e. peritonitis, rebound tenderness) or other clinical signs of intestinal ischemia (shock, persistent lactic acidosis, high grade radiographic findings), patients be emergently evaluated for exploratory laparotomy and resection of ischemic/necrotic small bowel.

Another consideration for non-cirrhotic PVTs includes superimposed infection / thrombophlebitis of the portal vein (pylephlebitis). Fever is present in up to 50% of patients, and not surprisingly, bacteremia is common (up to 70% of cases). Infection is often with gut-specific bacteria (gram negative and anaerobic species). In these cases, management involves antimicrobials in addition to systemic anticoagulation.

Other PVTs in patients without Cirrhosis

Management is typically with systemic anticoagulation in non-tumoral PVT, especially if the clot is recent, like in our patient. Recanalization rates vary considerably, from 16% to up to 71%. Current guidelines recommend a minimum treatment duration of 6 months if the predisposing factor has been reversed, however patients with thrombophilias often have indications for lifelong anticoagulation. The majority of literature has focused on low-molecular weight heparin as the treatment of choice but the use of DOACs appears encouraging in the recent literature. However, given the lack of robust, high-quality data on DOACs in non-cirrhotic PVTs, LMWH and vitamin K antagonists (warfarin) are more commonly prescribed in the acute phase. DOACs are increasingly used for provoked PVTs or as maintenance anticoagulant after stabilization or resolution of the acute PVT, if ongoing anticoagulation is indicated and no contraindications are present.

BUT what if?

A. Progression of Thrombus despite medical therapy

- Possible features of imminent bowel infarction → endovascular thrombolysis or surgical intervention are necessary

- Endovascular thrombolysis (may involve TIPS) have high rates of recanalization (in the 90% range)

B. Her Clot was a Chronic Non-Cirrhotic PVT

- May be associated with Ascites, Gastroesophageal Varices, Splenomegaly

- Primary (NSBB or EVL) and Secondary prophylaxis for bleeding are recommended, with note made most evidence for this is extrapolated from the cirrhosis population.

- Especially with established collaterals, there is less benefit of anticoagulant or interventional therapy (focus should be on managing portal hypertensive complications as a result of the PVT) in patients without underlying thrombophilia. Because our patient has a potent thrombophilia, she would still need lifelong anticoagulation.