Why do we use the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score?: Part 1

The Model for End-stage Liver Disease (or MELD) score is used to determine patient priority for liver transplantation. But have you ever wondered why?

Let us review the history and the literature to better understand why this score is so meaningful!

What came before the MELD score?

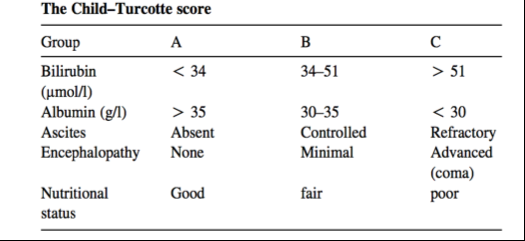

Prior to 2002, the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) classification was used to determine prognosis in patients with liver disease as well as to stratify patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation.

Remember, the CTP classification was originally proposed by two surgeons at the University of Michigan in 1964—Charles Gardner Child and Jeremiah Turcotte—and was designed to assess operative risk in patients undergoing surgical portosystemic shunt.

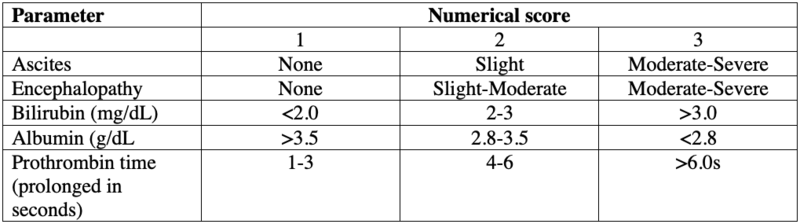

The original version of this score looked like this:

In 1972, the score was revised by Pugh to exclude nutritional status** (see footnote below) and to add prothrombin time. It is currently calculated based on:

- serum bilirubin

- serum albumin

- prothrombin time

- ascites <-- subjective

- encephalopathy <-- subjective

______

**Maybe the Child-Turcotte score was on to something with inclusion of nutritional status. Today, the field of frailty/disability/performance status research is HOT. These elements are likely very important in predicting survival but are not captured in the current Child-Pugh and MELD scores. More to come on this in Part 2….

______

Each of these variables is then assigned a numerical score and by adding the numerical scores of the individual components, Child-Pugh Class is calculated!

Child’s Pugh Class A: 5-6 points

Child’s Pugh Class B: 7-9 points

Child’s Pugh Class C: 10-15 points

Note, that using this classification, scores for ascites and encephalopathy could be dramatically different depending on whether a patient is adequately controlled on treatment. For ascites, for example, a patient may present with moderate-severe ascites and get a score of 3, but once Lasix and spironolactone are started, the score may decrease to 2 or even 1. Similarly, with hepatic encephalopathy, treatment with lactulose +/- rifaximin could bring a score from 3 to 1.

According to this classification system, one-year survival rates for patients within each category are as follows:

- Class A: 100%

- Class B: 80%

- Class C: 45%

Using these classifications, in the past, UNOS defined three categories of disease severity for listing:

- Status 3: CTP score of 7-9

- Status 2B: CTP score ³10

- Status 2A: Patients deemed “at risk of dying within seven days”: But this is subjective and not based on validated criteria!

Though this was the best predictive model that existed at the time, it had several limitations including:

- subjective interpretation of ascites and encephalopathyBecause of this, the system was often gamed for status 2A patients. Not all were equal! A patient with a variceal bleed and a bilirubin of 30 could share this status with a patient with refractory ascites

- limited discriminatory ability (i.e. a patient with a bilirubin of 4 mg/dL is assigned the same number of points as a patient with a bilirubin of 15 mg/dL!)

On to the MELD!

Clearly, we needed a better system to prioritize patients on the liver transplant waiting list.

So what about the MELD??

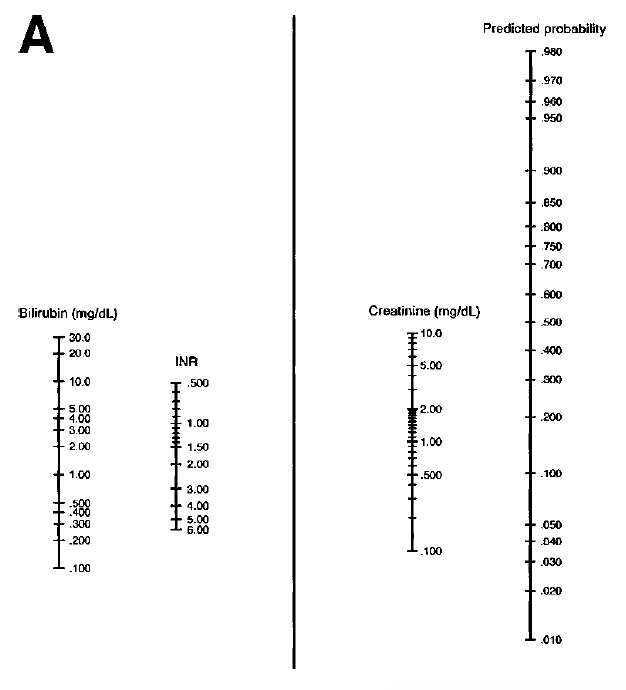

The MELD model was originally developed to assess short-term prognosis of patients with cirrhosis undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. In the original study conducted in 2000, assessing the performance of the model, MELD was better able to predict survival compared to the Child-Pugh classification in 231 patients undergoing TIPS for prevention of variceal rebleeding or for refractory ascites.

The authors of this study developed a nomogram that could be used to predict the likelihood of dying within 3 months after placement of TIPS and all you need is a ruler to measure it!

In 2001, a consortium of investigators studied the generalizability of the MELD to predict survival in patients with a broader range of disease severity and etiology. The group tested the model in four different patient populations:

- hospitalized patients with decompensated cirrhosis

- outpatients with non-cholestatic cirrhosis

- patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)

- historical patients with cirrhosis from the 1980s

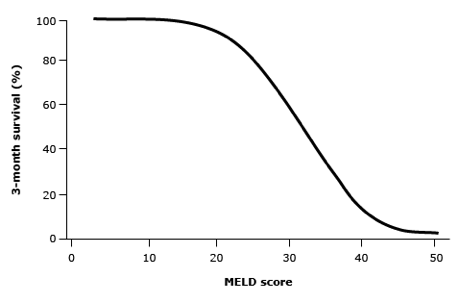

In these populations, the MELD score performed well in predicting death within three-months.

The researchers also assessed the impact of adding individual complications of portal hypertension (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, or ascites) and etiology of liver disease to the model and neither of these components had a large impact on its predictive power.

**Finally, in February 2002, the allocation system for liver transplantation switched from being based on CTP classification to the MELD score.**

What is included in the MELD score?

The MELD score uses patient laboratory values to predict three-month survival in patients with cirrhosis including:

- serum bilirubin

- international normalized ratio (INR) for prothrombin time

- serum creatinine

A formula is then used to calculate the score and three-month mortality can then be predicted (as seen below).

MELD = 3.8*loge(serum bilirubin [mg/dL]) + 11.2*loge(INR) + 9.6*loge(serum creatinine [mg/dL]) + 6.4

The lowest score is a MELD of 6 and the highest, a MELD of 40.

The maximum serum creatinine level was set to 4mg/dL (which is also the value assigned to those on hemodialysis) to avoid unfair advantages to those with intrinsic renal disease.

Why was sodium added?

As the MELD score was implemented, it became clear that certain patients were under-represented by their scores. There has always been a desire to continue to improve the score by altering existing variables or adding new ones that are objective and reproducible. Serum sodium is one such variable that has been extensively studied.

Hyponatremia is a frequent complication of cirrhosis, especially in those with ascites, and has been shown to worsen in the setting of any hypovolemia-inducing event, including infection and bleeding. Even prior to its incorporation into the MELD, multiple studies had demonstrated hyponatremia to be a negative prognostic factor associated with increased mortality (see studies 1 and 2 here). It additionally often predicts hepatorenal syndrome, which in and of itself, increases mortality.

In 2008, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that the addition of serum sodium to the MELD score had better predictive power for mortality than the MELD score alone.

In this study, mortality increased by 5% for each mmol decrease in serum sodium between 125 and 140 mmol/L.

However, it was not until 2016, that the UNOS updated their allocation system to include sodium.

Limitations of the sodium in the MELD score include:

- The use of diuretics

- The use of intravenous fluids

Despite these limitations, the MELD score is still the best predictive model we have and continues to be used for allocation.

How is the MELD used in transplant listing?

Now that we understand the history behind the MELD and the variables included in its calculation, how is it actually used?

When determining liver allocation, the following factors are considered:

- The patient’s medical urgency <-- Determined by MELD

- How close the patient’s transplant hospital is to the donor hospital

- Blood type compatibility

- How long patients have waited in their current urgency status or higher status

You may wonder, however, about what happens when a patient’s MELD score changes??

- Scores are updated at regular intervals depending on the initial MELD score (i.e. those with higher MELD scores have their scores updated more frequently)

- If an individual’s MELD score increases, their wait time resets to zero

- If an individual’s MELD score decreases, their wait time at the higher MELD is added to their wait time at the lower MELD

Thinking Ahead…

In Part 2 on the topic of MELD, we will be discussing MELD exception points, disparities in liver transplantation after the introduction of the MELD, and continued problems with the score.