Why do we care about frailty in liver disease?

Frailty is a prevalent complication of end-stage liver disease and is characterized by decreased physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to health stressors. The concept of frailty matters in liver disease because it can significantly impact patient outcomes. Frailty is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with liver disease, including higher waitlist and post-transplant mortality. Frailty can also affect the ability of patients to tolerate treatments, such as surgery, and can also impact their overall quality of life. Identifying and addressing frailty in patients with liver disease is therefore important for optimizing their care, improving outcomes, and improving quality of life. This post seeks to explain why frailty matters, how to assess it, and what we can do about it.

Definitions

More than half of patients with cirrhosis suffer from frailty and/or sarcopenia, which portends worse morbidity and mortality including in pre- and post-transplant patients. But what exactly is ‘frailty’, how can we measure it, and what can we do about it?

It is important to clarify the different terminology used surrounding frailty. The concepts of frailty, sarcopenia, and malnutrition are all interrelated. The below diagram shows how malnutrition is one factor (of many) that leads to sarcopenia and/or frailty.

Figure 1. Figure from Lai et al

AASLD Guideline on malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia published in 2021 seek to standardize the definitions as follows:

| Construct | Theoretical Definitions | Practical Definitions |

| Malnutrition | A clinical syndrome that results from deficiencies or excesses of nutrient intake, imbalance of essential nutrients, or impaired nutrient use | An imbalance (deficiency or excess) of nutrients that causes measurable adverse effects on tissue/body form (body shape, size, composition) or function and/or clinical outcome |

| Frailty | A clinical state of decreased physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to health stressors | The phenotypic representation of impaired muscle contractile function |

| Sarcopenia | A progressive and generalized skeletal muscle disorder associated with an increased likelihood of adverse outcomes including falls, fractures, disability, and mortality | The phenotypic representation of loss of muscle mass |

Table 1. Definitions for the Theoretical Constructs of Malnutrition, Frailty, and Sarcopenia and Consensus-Derived Operational Definitions Applied to Patients with Cirrhosis. Lai, Tandon et al. 2021. Hepatology.

The theoretical definition of frailty stems from the field of geriatrics which posits frailty as something that can be screened for, potentially prevented, and treated. Frailty is a dynamic condition that includes physical and psychological components. In liver disease, the predominant focus has been on physical frailty. This is primarily because physical frailty has clear clinical manifestations in cirrhosis including decreased physical function, decreased functional performance, and disability as the result of impaired muscle contractile function. This is defined separately from sarcopenia (decreased muscle mass) and malnutrition (the imbalance of nutrients which causes adverse events on the body), though all three are inextricably linked.

Why do patients with cirrhosis have worse malnutrition/sarcopenia?

There is a negative energy balance in patients with cirrhosis that is primarily driven by low food intake. Moreover, decompensated disease commonly presents with the presence of ascites, which is associated with loss of appetite, difficulty moving, reduced stomach capacity, and poor digestion. Fortunately, ascites removal decreases baseline resting energy expenditure in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Resting energy expenditure can be measured through calorimetry, which has been shown to be a more accurate metric than prediction models. Additionally, therapeutic paracentesis has been shown to help with restoring appetite and decreasing feelings of fullness which in turns improves diet and exercise capacity.

Similar to how decompensated cirrhosis symptom of ascites affects frailty, so too does hepatic encephalopathy. One study of 685 patients with cirrhosis demonstrated that hepatic encephalopathy was associated with multiple measures of frailty including grip, walk speed, and decreased energy. The RIVET study, a phase 2 placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized clinical trial, suggests that treating hepatic encephalopathy can improve surrogate measures of frailty including lean mass and handgrip strength.

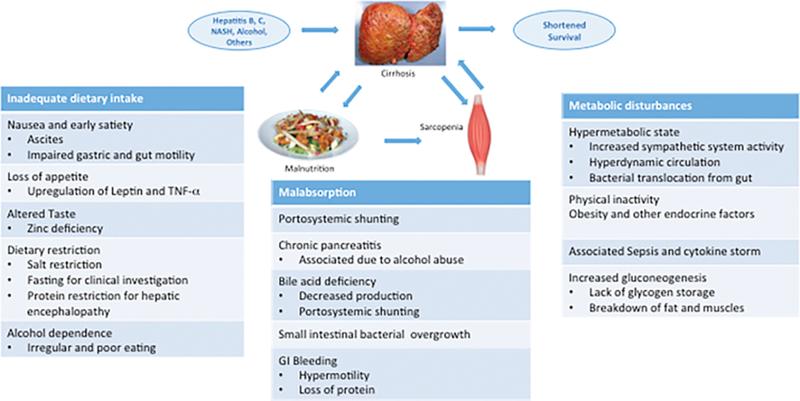

An article from 2017 helps to break down the complexity of malnutrition and sarcopenia on cirrhosis with a figure that demonstrates the complexity of inadequate dietary intake, malabsorption, and metabolic disturbances.

Figure 3 Cirrhosis malnutrition and sarcopenia etiologies. Reproduced from Anand 2017.

Why does frailty matter in chronic liver disease?

Why is this specifically important in patients with cirrhosis?

- It's common!

Frailty has been shown to be present in upwards of a quarter of pre-transplanted ambulatory patients and is independently associated with wait-list mortality. Validated measures of frailty (discussed below) have mainly been studied in the ambulatory setting, though there is evidence that the prevalence is even higher in inpatients. As signs of decompensation increase (worsening ascites, or encephalopathy), frailty also worsens.

- It is associated with worse outcomes.

Frailty is directly associated with cirrhosis progression, unplanned hospitalization, and death. There has been shown to be increased risk of death in patients awaiting transplant. In this study of 9 transplant centers, there was a higher incidence of frailty amongst patients with encephalopathy and ascites. Moreover, this study showed that for patients with ascites or encephalopathy, there was a higher odds of mortality if frailty was present. Frailty has also been well documented to have worsened mortality and post-surgical complications and as length of stay in elective surgeries.

- Impact on transplant

In addition to increased waitlist mortality, frailty has also been shown to have worsened post-transplant complications including increased length of stay. However, frailty or existence of sarcopenia is not recommended as a contraindication to transplant.

Why is frailty worse with decompensated liver disease?

Understanding why frailty exacerbates morbidity and mortality in decompensated liver disease is crucial, especially given the high prevalence. Various factors have been shown to impact frailty that are worse within the population of patients with decompensated liver disease.

1. Disease related malnutrition: Decompensated liver disease is a catabolic state that can lead to malnutrition, which contributes to muscle wasting and weakness, exacerbating frailty.

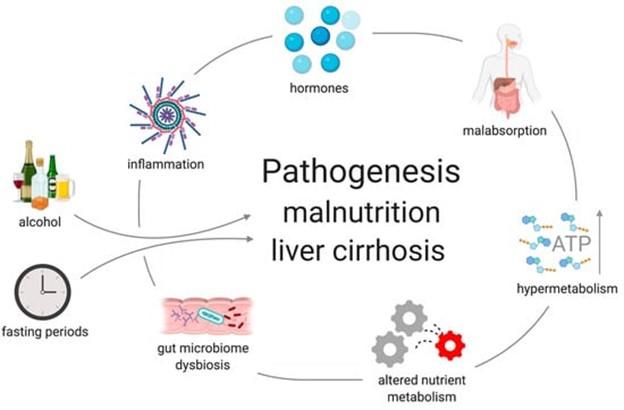

Disease-related malnutrition describes a nutrition- and inflammation-related disorder that results from prolonged acute or chronic disease and lack of nutrient intake or absorption leading to compromised body composition and function. The etiology of malnutrition is multifactorial and results from decreased intake, inflammation, malabsorption, altered nutrient metabolism, hormonal disturbances, and dysbiosis, as seen in the figure below.

Figure 2. Factors contributing to malnutrition in liver disease. From Traub et al.

In liver disease malnutrition is typically seen through the phenotype of loss of muscle mass with or without loss of adipose tissue. According to the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM), the diagnosis of disease related malnutrition requires a combination of at least one phenotypic and one etiologic criteria to be met. Phenotypic criteria include non-volitional weight loss, low body-mass index, or reduced muscle mass. Etiologic criteria include reduced food intake or assimilation, and inflammation, or disease burden. Once established, malnutrition can be further categorized by severity.

More information on malnutrition in liver disease can be found here.

2. Sarcopenia: Decompensated liver disease is often associated with sarcopenia, a condition characterized by loss of muscle mass and function, which is a key component of frailty.

While the pathogenesis of sarcopenia is multifactorial, it is essentially an imbalance between protein synthesis and protein breakdown. Cirrhosis is a catabolic state of accelerated starvation, with increased gluconeogenesis that requires amino acid diversion from other metabolic functions. Its prevalence in patients with cirrhosis and association with mortality have caused some to argue of its inclusion in cirrhosis assessment tools such as a MELD-Sarcopenia.

Malnutrition and muscle wasting, sarcopenia, are common in cirrhosis but difficult to diagnose especially if ascites or obesity are present. There is some evidence that hyperammonemia seen commonly in patients with cirrhosis can lead to inhibition of protein synthesis and increased protein catabolism as well as impaired strength and increased muscle fatigue. Moreover, many patients with cirrhosis have a combination of sarcopenia and increased adipose tissue, commonly referred to as “sarcopenic obesity.” Sarcopenia in this population has been shown to have an association with increased mortality even without a correlation with liver dysfunction severity. Additionally, sarcopenia in liver disease has been associated with complications from sepsis, overt hepatic encephalopathy, and increased length of hospitalization post liver transplantation.

Sarcopenia is very prevalent in liver disease affecting 30%-70% of patients with cirrhosis, which is unsurprising given the high catabolic state of cirrhosis. There are differences in sarcopenia based on etiology of cirrhosis with worsened prevalence amongst alcohol-related etiology. Sarcopenic obesity is noted amongst patients with MASLD and drives mortality. While there is a significant contribution to sarcopenia by malnutrition as described above, additional factors affect the development of sarcopenia in liver disease including altered lipid and amino acid metabolism (decreased gluconeogenesis, increased ketogenesis, increased whole-body protein turnover), hyperammonemia, increased inflammatory markers, increased myostatin, decreased anabolic hormones (IGF-1 and testosterone), and inactivity. This condition is worsened by the lack of current treatments available to reverse or prevent sarcopenia.

While CT imaging is the current gold standard for assessment of muscle mass, given cost and radiation, it is not currently recommended as a means to only assess for sarcopenia.

3. Inflammation

Chronic liver disease, even in the absence of cirrhosis, is a state of chronic inflammation given the elevated levels of inflammatory markers, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, C-reactive protein, and TNF-α. This chronic inflammation, possibly exacerbated by low-grade endotoxemia due to increased gut permeability and altered gut microbiome, may contribute to frailty and sarcopenia by reducing muscle protein synthesis and increasing protein degradation.

4. Inactivity

Physical inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle can be common amongst patients with cirrhosis. One study of patients listed for transplant demonstrated over that three-quarters of patients were fairly sedentary with a median of only 3000 steps per day.

5. Hormones

Testosterone is an anabolic hormone that plays many roles including the maintenance of muscle mass and bone mineral density, as well as having effects on mood, libido, lipolysis, and insulin resistance. Outside of liver disease, low levels of serum testosterone have been associated with numerous comorbidities including anemia and sarcopenia. This is particularly notable in male patients with cirrhosis who often have lower levels of testosterone due to central hypothalamus-pituitary dysfunction, increased peripheral aromatization of estrogens, and gonadal failure.

Upwards of 90% of men with cirrhosis have low serum testosterone levels. Consequently, low serum testosterone is correlated to higher rates of decompensation and mortality in addition to sarcopenia and frailty.

However, exogenous supplementation has not consistently been shown to ameliorate outcomes such as decompensation and mortality, though data suggests supplementation can safely be used in patients with cirrhosis to increase muscle mass, bone mass, hemoglobin, reducing fat mass, and reducing hemoglobin A1c. Current recommendations are to check baseline testosterone levels in male patients with cirrhosis and can consider testosterone supplementation to improve muscle mass if there is no history of HCC, other malignancy, or thrombosis.

6. Social determinants of health

Factors such as health literacy, food insecurity, financial strain, and caregiver responsibility have been shown to have association with worsened health status and directly or hypothesized association with frailty.

How can we measure frailty?

Existing cirrhosis assessments such as MELD and Child-Pugh primarily focus on overt manifestations of hepatic dysfunction and can overlook the broader impact of cirrhosis on patients' well-being and quality of life. There are a handful of tools used to measure frailty in ambulatory patients with end stage liver disease. These scores vary in their predictive abilities and applicability, with some being more suitable for certain patient populations or settings. There is not a standardized metric and as such there is not consistency in which tool providers use. Some of the tools uses to measure frailty have more subjective or objective variables included to assess overall frailty. Below are examples of a few of the tools that have been studied in this context, though this is far from a comprehensive list.

Activities of daily living (ADLs)

- One study with self reported ADLs and IADLs (Instrumental ADL) of 458 patients found that the most prevalent ADL deficits amongst liver transplant waitlist patients included continence, dressing, and transferring, with the most prevalent IADLs lost being shopping, food preparation, and medication management.

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS)

- KPS has been used for over 70 years in clinical practice. The linked study showed how KPS scores declined between listing and transplantation but subsequently improved. (Great news!) It also showed how KPS was an independent predictor of graft and patient survival.

- A UNOS database study showed how performance status based on KPS was associated with mortality.

- Another large database study showed how pre transplant KPS score can be predictive of post transplant survival.

- A simple, non-exertional test that assesses global physical function. It has been validated to predict mortality in heart failure, COPD, pulmonary hypertension, and pre-lung transplant patients.

- One study demonstrated that each 100-m increase in the 6 minute walk test was significantly associated with increased survival (hazard ratio of 0.48), with a distance of less than 250m being associated with increased risk of death on the wait list.

- The LFI consists of measurements grip strength, chair stands, and balance which posits ability to measure longitudinally in clinical practice. It has been shown to be predictive of waitlist mortality with optimal cut off of 4.4 at 3 months and 4.2 at 6 and 12 months.

- Another study demonstrated that worsening frailty was associated with worse outcomes with a regression demonstrating that a 0.1 unit change in LFI per three months was associated with a 2.04 fold increased risk of death or delisting.

- One study showed that for each LFI point increase, there was a 2.6 odds higher of having difficulty with at least one ADL and 1.7 odds higher for IADLs.

What can we do about frailty?

There is not a lot of evidence yet demonstrating reversibility of frailty, though some studies do offer promise. One example is the STRIVE study, the largest multi-center RCT of an ambulatory intervention. This study found minimal improvement in LFI, but did demonstrate improved quality of life and proposed that the limitations on LFI improvement were through adherence to the strength training intervention.

Frailty interventions can be broken down into three categories of primary, secondary, and tertiary interventions. All patients with cirrhosis should receive a malnutrition screening to assess which type of intervention would be most appropriate.

For primary interventions the goal is to prevent or delay development of frailty. For primary intervention, all patients should receive education about frailty in addition to motivation and behavioral skills to help prevent development of frailty.

Secondary intervention focuses on early diagnosis and prompt treatment initiation. Assessment of underlying etiologic risk factors after a positive malnutrition screen should take place as well as development of a personalized management plan. These patients should be reassessed at least annually, if not more frequently.

Tertiary interventions are about reversal and rehabilitation. Patients who have progressive frailty despite intervention should have a multidisciplinary approach to rehabilitation with physical rehabilitation and nutrition and dietician support.

Liver disease specific interventions can help progression of frailty as well. The treatment of HCV or the cessation of alcohol use, in addition to management of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy can be useful in helping to address frailty. For example, some evidence supports that while also helping refractory ascites, the use of TIPS can improve nutritional status, though there is conflicting evidence about improvement in muscle mass. Nutritional education is also important in this population. More about nutrition in liver disease can be found here and here. Intake related interventions and physical activity interventions are both important tools to help prevent and reverse frailty. There are some studies which show additionally that hormonal therapies such as testosterone therapy in men with cirrhosis can help with frailty measures.

Take home points:

- Frailty is defined as a clinical state of decreased physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to health stressors.

- Frailty significantly affects patient outcomes in liver disease including increased morbidity and mortality.

- Frailty is directly associated with cirrhosis progression, unplanned hospitalization, and death, with a higher incidence in patients with encephalopathy and ascites.

- Disease-related malnutrition, sarcopenia, chronic inflammation, inactivity, and social determinants of health all contribute to frailty in cirrhosis.

- Frailty can be measured using various tools including the Liver Frailty Index. The majority of frailty measurements have been done in the outpatient setting.

- All patients should undergo a baseline assessment and longitudinal assessment of frailty at least annually. There is no current consensus on which method to utilize.

- Patients should receive primary prevention for frailty through education, motivation, and behavioral skills.

- A positive screening for frailty or sarcopenia should prompt an investigation into underlying etiology. Progressive disease should prompt multidisciplinary approach including coordination with dieticians and physical therapists.

- Micronutrient deficiency should be checked annually and repleted.

- Physical activity-based interventions are recommended.