Why do people with primary sclerosing cholangitis require so much cancer screening?

Introduction

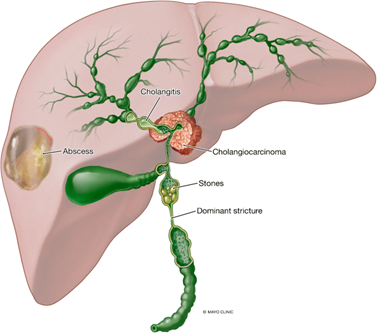

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a heterogenous and progressive disease of the biliary tree, resulting in fibrosis and the eventual development of cirrhosis. Due to recurrent immune-mediated inflammatory attacks on the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts, individuals with PSC develop fibrotic strictures. The chronic cholestasis from these strictures lead to numerous complications including gallstones, recurrent cholangitis, and abscess development (Figure 1). The combination of inflammation and cholestasis is also highly carcinogenic, leading to biliary cancer in these patients. As there is currently no disease-modifying therapy for PSC, management is largely the treatment of complications as they develop. Even with specialized care, the typical individual with PSC will require liver transplant or die from complications between 9 and 20 years from diagnosis.

Figure 1: Complications of chronic biliary obstruction due to primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), including cholangiocarcinoma.

Malignancy remains a significant contributing factor to mortality in patients with PSC. Case series of individuals with PSC and ulcerative colitis were first reported in the 1960s, with two of the first case series published noting a patient died from hepatic duct carcinoma and another from UC-related colon cancer. Since these early characterizations of PSC, the relationship between PSC and malignancy has been well established. In particular, patients with PSC are at increased risk for hepatobiliary (cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma) and colorectal cancers. Thus, the foundation of care for people with PSC includes appropriate screening protocols to identify these malignancies at early stages to improve outcomes.

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA)

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is an uncommon cancer of the bile ducts with a very poor prognosis. While symptoms such as pruritus and jaundice are common at presentation, many people with CCA are asymptomatic. For patients diagnosed with late-stage CCA, expected survival is a dismal 11.7 months. Yet for those with surgically resectable disease, the median overall survival is significantly higher at 51.1 months. Detection at an early stage also allows for consideration for liver transplantation in select individuals. Consequently, early identification is a critical way to potentially improve outcomes in CCA.

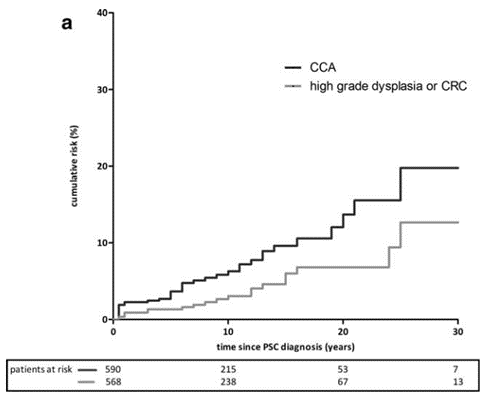

While relatively rare in the general population, people with PSC are up to 400 times more likely to develop CCA. Though the exact driving mechanisms are not completely understood, it is thought that chronic cholestasis in PSC causes ongoing inflammation in the biliary tree that promotes the development of malignancy. It also remains unclear why PSC patients have higher rates of CCA than those with other cholestatic liver disease. Incidence of CCA is highest in the first year of PSC diagnosis (2.5%), but it can develop any time throughout a patient’s life. By 30 years, the risk of developing CCA is as high as 20%. Other risk factors for development of CCA in PSC patients include smoking, alcohol use, concomitant inflammatory bowel disease, and presence of colorectal cancer or dysplasia.

Due to the differential survival in early-stage disease and high incidence in PSC patients, screening for CCA is routinely performed. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) currently recommends annual screening for CCA in adults with large-duct PSC. The primary aim of screening is the early identification CCA to increase the probability of curative treatment. At present, there remains no consensus with respect to the ideal screening modality and interval.

Figure 2: Cumulative incidence of CCA and high-grade colorectal dysplasia or colorectal cancer (CRC) in individuals with PSC. Note the cumulative risk of up to 20% of CCA in the 30 years following PSC diagnosis.

Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (eCCA)

Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (eCCA) refers to CCA found below the second order bile ducts of the liver. eCCA can be further subdivided into perihilar (pCCA) which involves the ducts of the hepatic hilum above the cystic duct, and distal (dCCA) which is below the cystic duct and above the ampulla of Vater. The most common type of eCCA in PSC patients is pCCA, which makes up >50% of all CCAs. Though typically presenting as an obstructive biliary stricture, eCCA may also appear as a compressive mass.

Due to its resolution and characterization of the extrahepatic biliary tree, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the primary screening modality for eCCA. While there are no pathognomonic imaging findings for eCCA, the presence of a dominant stricture or interval development of a new stricture should raise suspicion. MRI/MRCP detection of CCA is associated with reduction in mortality when compared to detection by other non-invasive tests such as abdominal ultrasound (US) (hazard ratio = 0.10).

Once a suspicious stricture or mass is identified on MRI/MRCP, complementary testing is performed to support a diagnosis of CCA. One biomarker that is often used in conjunction with imaging in screening for CCA is carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9). A glycolipid found in the biliary epithelium, CA 19-9 is often expressed by CCA cells resulting in elevated serum concentrations. Because up to 33% of PSC patients have elevated CA 19-9 without CCA or other underlying cause, it is not useful as a solitary screening modality. When combined with MRI/MRCP, use of CA 19-9 has a sensitivity of nearly 100% for CCA, but a specificity of 38%. For these reasons, the AASLD does not recommend for or against the use of CA 19-9 as part of CCA screening.

Often, imaging and serologic testing is insufficient to make a diagnosis of eCCA. These patients are generally referred for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to allow direct sampling from the duct for analysis. Diagnostic yield from conventional cytology of duct brushings is poor, with less than 10% sensitivity in making a definitive eCCA diagnosis. The use of genetic analysis for polysomy by fluorescence in situ hybridization has shown to increase specificity, but only increases sensitivity to 38%. In cases where a diagnosis of eCCA cannot be clearly established, close monitoring is often performed with repeat imaging or endoscopic evaluation in 3 to 6 months to assess for changes and/or repeat tissue sampling.

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA)

In comparison to eCCA, surveillance and diagnosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) tends to be more straightforward. Complementary to its extrahepatic counterpart, iCCA is defined as CCA above the second order bile ducts. There is also evidence that iCCA may be a separate disease entity from eCCA. Though seen in patients with PSC, iCCA is far less common than eCCA in this cohort.

Similar to eCCA, the surveillance for iCCA begins with MRI/MRCP. Typical findings include a mass-like lesion with hypointensity on T1-weighted images, hyperintensity on T2-weighted images, arterial phase peripheral enhancement with progressive concentric filling-in with contrast. Once a suspicious lesion is identified, biopsy may or may not be needed depending on the clinical scenario. In patients with highly suggestive imaging and for whom resection is feasible, surgery can be pursued in the absence of prior histopathologic confirmation. However, biopsy (percutaneous, transvascular, or endoscopic) is often needed to confirm diagnosis and staging in order to create a definitive treatment plan.

Despite significant efforts in screening, it is unclear if current recommendations are adequate in reducing CCA-associated mortality. One large Swedish cohort study in which over 500 PSC patients were screened with annual MRI/MRCP and CA 19-9, there was no significant improvement in mortality. The applicability of these findings the United States patient population is uncertain. An individualized approach, including discussions with patients regarding the benefits and harms of screening, is recommended.

Gallbladder Cancer

Similar to CCA, patients with PSC are at a markedly increased risk for gallbladder cancer. Though the literature is varied, it is estimated that the prevalence of GBC in people with PSC is between 2.5% and 3.5%, with some studies reporting up to 21%. This increased risk is thought to be a consequence of chronic gallbladder inflammation that accelerates the metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence. Also like CCA, the prognosis of GBC is poor with an overall 5 year survival less than 5%.

Gallbladder polyps are pre-cancerous lesions (typically adenomas) that can be seen on imaging before progressing to carcinoma. While they can be seen on MRI/MRCP, existing literature suggests they are best identified on abdominal US (sensitivity 84%, specificity 96%). These lesions are commonly seen in individuals without PSC, but the presence of concomitant PSC is associated with a significantly higher risk of malignant transformation. The AASLD currently recommends surveillance of gallbladder polyps ≤8 mm with US every 6 months and referral for cholecystectomy for polyps 9 mm or greater. The decision to proceed with surgery often requires multidisciplinary discussion, as individuals with advanced liver disease are at significantly higher risk for post-operative complications. There remains no specific guidance regarding gallbladder cancer surveillance of individuals with PSC without known gallbladder polyp.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is primary liver malignancy that disproportionately affects patients with cirrhosis and chronic liver disease. Risk of developing HCC is highest in patients with chronic viral hepatitis (hepatitis B and C), hemochromatosis, alcohol-associated liver disease, with emerging evidence suggesting high risk in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. When compared to those with cirrhosis from other etiologies, individuals with PSC have a relatively low risk of developing HCC. In one study, of 119 people with PSC and cirrhosis, none developed HCC over 292 person-years. Thirty-five cases of CCA and 3 cases of gallbladder cancer were identified in this same cohort—highlighting the relatively low risk of HCC in relation to other cancers in people with PSC. As there is a relative paucity of data in regards to HCC in PSC patients, it is reasonable to screen those with PSC-associated cirrhosis similar those with cirrhosis from other causes. The AASLD recommends surveillance for HCC in PSC-associated cirrhosis according to current guidelines, which are abdominal US with serum alpha fetoprotein every 6 months.

Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the world. Given its prevalence and advent of excellent screening modalities, the United States Preventative Services Task Force advocates for a population-based screening program. For the average individual, CRC screening can be performed using stool-based testing or direct visualization testing such as CT colonography or colonoscopy beginning at age 45.

Individuals with PSC have a significantly elevated risk for CRC compared to the general population (relative risk = 9), with an increased incidence at a younger age (median 41 years vs. 66 years). This is primarily driven by the high comorbidity of PSC with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a clinical syndrome that is often referred to as PSC-IBD, with over 70% of patients with PSC either having or at risk for developing IBD. In one cohort, colorectal cancer developed in 10% of those with PSC-IBD. Due to its higher sensitivity, specificity, and therapeutic potential in removing dysplasia, colonoscopy is the recommended modality for CRC screening in PSC patients.

Given the high percentage of patients with PSC having IBD, a diagnostic colonoscopy is recommended at time of PSC diagnosis to establish whether concomitant IBD is present. Once a diagnosis of PSC-IBD has been established or ruled out, patients are shunted into their respective CRC screening protocols.

- For those with PSC without IBD, CRC screening is recommended every 5 years with colonoscopy or sooner if there is clinical suspicion for interval development of IBD.

- In patients with PSC-IBD, colonoscopy should be performed every 1-to-2 years with dysplasia surveillance starting at time of diagnosis or at age 15 (pediatric onset).

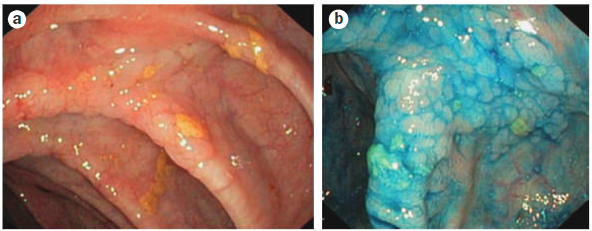

Dysplasia surveillance is performed by careful examination under high-resolution white light endoscopy and random colonic biopsies (typically every 10cm), with or without an alternative viewing modality such as chromoendoscopy or narrow-band imaging (Figure 3). Studies have shown that dysplasia surveillance protocols in IBD reduces rates of CRC, though data for PSC-IBD is less robust. Surveillance does appear to reduce CRC-associated mortality in PSC-IBD patients. In one large Dutch cohort of individuals with PSC-IBD diagnosed with CRC, those who were surveilled had a CRC-associated mortality of 16% compared to 50% in those who were not surveilled. This is in contrast to medical therapies, which do not appear to play a role in reducing risk of CRC. In a follow-up study of patients with PSC on high-dose ursodiol, the risk of CRC was actually increased compared to placebo.

Figure 3: Colonoscopic images from a 20-year-old male with PSC and colitis. (a) Colorectal dysplasia under high-resolution white light colonoscopy. (b) Same colonic segment after chromoendoscopy.

Conclusion

Malignancy continues to remain a significant concern for patients with PSC. In particular, individuals with PSC are at markedly increased risk for CCA, gallbladder cancer, and colorectal cancer compared to people with other liver diseases. This is in addition to the increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma for patients with PSC and cirrhosis. Fortunately, screening for all of these cancers is achieved with MRI/MRCP and colonoscopy, with further evaluation depending on these data. While finding these cancers early can improve outcomes for some, significant improvements are needed to increase early detection—particularly for CCA.

Key Points

- Individuals with PSC have significant risk for developing hepatobiliary and colorectal cancers.

- CCA screening should occur annually, typically with an MRI/MRCP +/- serum CA 19-9.

- People with PSC and gallbladder polyps should undergo abdominal US every 6 months and be referred for evaluation for cholecystectomy when polyps are >8mm in size given the risk for malignant transformation.

- PSC without cirrhosis does not appear to increase the risk for HCC. Routine HCC screening with abdominal US and alpha fetoprotein should occur every 6 months for individuals with PSC-associated cirrhosis.

- Once a diagnosis of PSC is made, a diagnostic colonoscopy should be performed to evaluate for concomitant IBD (PSC-IBD). In the absence of IBD, colonoscopy should be performed every 5 years for CRC screening.

- For individuals with PSC-IBD, colonoscopy should be performed every 1-2 years with dysplasia surveillance.