Transitions of Care

Healthcare Transition for Pediatric Liver Transplant Patients

Definitions

Healthcare transition (HCT) is defined as the active process that addresses the medical, psychosocial, and educational/vocational needs of adolescents as they transition to an adult model of healthcare. Transfer, on the other hand, is the physical change in location where care is provided.

Why is Transition of Care Important?

HCT has become an increasingly important area of study due to the fact that patient and graft survival have improved drastically over the last several decades. Therefore an increasing number of pediatric patients who have received liver transplantation (LT) are surviving into adulthood and entering adult-centered transplant and hepatology services. The challenge now shifts towards optimization of long-term outcomes for these LT recipients.

Evidence suggests that the risk for poor patient survival outcomes increases over time starting at 10-15 years after transplantation. In general, the mortality rate of healthy 18- to 24-year olds is more than twice that of those ages 12-17 years. Substance use peaks around this age, and the suicide rate in this age group is nearly triple that of those 12-17 years old. Having a serious medical diagnosis and receiving a liver transplant are added stressors that compound these other psychosocial stressors in this high risk population. Thus it is no surprise that there is an increased risk for medical complications and morbidity following transfer from pediatric to adult healthcare services in patients with childhood onset chronic illness such as liver disease.

Additionally, in a study by Chandra et al, the majority of pediatric patients transitioning to adult providers had a lag time of 2-6 months, with some patients having a lag time up to even a year, before being seen by an adult provider. During this “limbo period” where patients have no primary provider, there is a trend towards worse health outcomes, decreased adherence, and increased healthcare costs and utilization.

Barriers to Transition of Care

Patient Barriers:

Adolescent LT recipients often lack the skills necessary for planning, organizing, initiating, and maintaining future-oriented problem solving. They often have poor adherence to medications, lab draws, and follow up, and limited ability to self-manage their medical conditions. They frequently lack knowledge of their past medical history and medications, and depend on their parents/guardians for support and decision making. Lapses or changes in health insurance may also be a challenge during this time period.

Pediatric Provider Barriers:

Many pediatric providers struggle with relinquishing care of their long-term patients. The unintended consequences of these strong attachments may inhibit patients and their families from developing new relationships with adult providers. Additionally, pediatric providers can be overly accommodating and pediatric care tends to be family-centered which may interfere with the development of age-appropriate self-management skills.

Adult Provider Barriers:

Adult providers encounter several challenges when caring for patients transitioning out of pediatric care and into adult care. Adult providers also want to maintain a family-centered approach, but need to support their patients in transitioning into a more independent and active role in their healthcare. Adult providers, however, often do not have specific training in this transition. This transition can be particularly difficult for the patient, who may feel ambivalent about transitioning into a more active role in their care or may have limited health literacy. Caregivers also may have trouble supporting the transitioning patient into a more independent role due to hesitancy surrounding relinquishing their more primary role.

Adult providers also have to balance increasing patient volumes and patient complexity, and often don’t have the same family-oriented resources that pediatric specialty clinics have. This can often be perceived by transitions of care patients as a decrement in patient-centered care, which may compromise engagement with the healthcare system and their providers.

Transitions of care often coincide with an age-range in which mental illnesses begin to surface, which can complicate adherence and engagement with care. Adult providers must be cognizant of this risk and provide appropriate screening and support for adolescents during this period.

Finally, many of the leading indications for pediatric liver transplantation are pediatric-specific diseases, with which adult providers are less familiar. It is essential that adult providers learn about and understand the nuances of these disease processes to provide high quality care. This can be challenging in a busy clinical practice with increasing patient volumes and patient complexity compounded by decreased time for self-study and educational activities.

Systemic Barriers:

As discussed previously, transition to adulthood is a time when insurance coverage is often insufficient or non-existent. Additionally, there is often a lag time between the last visit with a pediatric provider and the first visit with the adult provider, which can result in issues with medication refills and lab draws, communication gaps, and inappropriate use of medical resources such as the emergency room. Lastly, there may not be institutional support available for a multidisciplinary approach to transition of care.

Transition Readiness

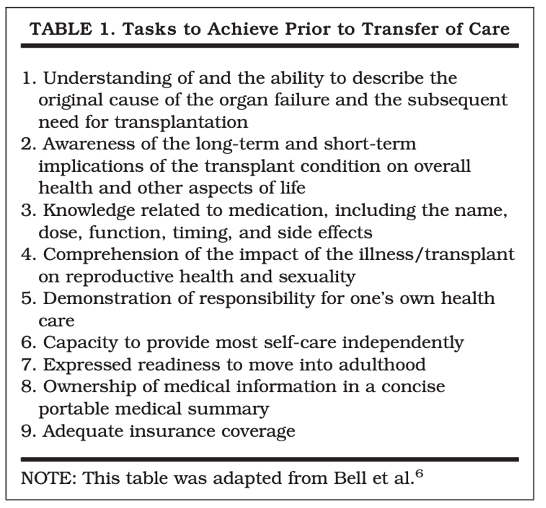

The transition process should begin in early adolescence, but adolescents and young adults should ideally transition from pediatric to adult healthcare providers when they have achieved the skills necessary for functioning effectively in the adult healthcare system. Through transition readiness assessment (TRA), the provider, patient, and family can work together to identify self-care goals and build the skills necessary to achieve these goals. Below is an outline of the tasks that are recommended to achieve prior to transfer of care:

The use of transition readiness assessment tools allows for an individualized approach to transition readiness. There are several validated transition readiness tools that have been utilized at routine intervals throughout the transition process, including the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ), the UNC STARx Questionnaire, and the Got Transition© Readiness Assessment for Youth. These tools are not specific to LT or chronic liver disease.

Approach to Transition of Care

Got Transition© has developed guidelines for the development of a transition program using six core elements as recommended by the AAP/AAFP/ACP Clinical Report on HCT. The goal of this structure is to enhance the delivery of transition services and improve long-term patient-centered outcomes with transition of care. It is important to note that the transition process does not stop with the pediatric provider, and in fact continues even after the patient has transferred care to adult health services.

| CORE ELEMENT | PEDIATRIC TEAM | ADULT TEAM | TRANSITION TOOLS AND REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Transition Policy |

|

|

|

| 2. Tracking and Monitoring |

|

|

|

| 3. Transition Readiness |

|

|

|

| 4. Transition Planning |

|

|

|

| 5. Transfer of Care |

|

|

|

| 6. Transition Completion |

|

|

Transition programs require a multidisciplinary team approach with hepatologists, transplant surgeons, nurses, pharmacists, dietitians, social workers, financial coordinators, psychologists, and psychiatrists from both the pediatric and adult teams. It is recommended that a leader such as a transition coordinator (nurse or advanced practitioner on the pediatric team) be appointed to each patient to ensure complete transition and provide continuity of care after transfer.

Measuring Outcomes

Several studies have examined outcomes of patients as they transition their care from pediatric to adult transplant specialty care. This period represents a high-risk time point in patient care, and outcomes seem to reflect this. In one study of 14 patients who received a LT, 4 patients died after transitioning care, whereas no deaths were recorded in the pediatric and adult cohort control groups. In another study of 32 liver transplant recipients transitioning care, 28% of transitioned patients died during study follow-up, and the median time to death after transition was 3.1 years. In both studies, non-adherence to medications and medical care were considered major contributors to poor outcomes. Other studies have reported better outcomes, however non-adherence to medication and recommended medical care remained high in the period after transitioning care.

Although it is important to measure longer-term clinical outcomes like rejection episodes, graft failure, re-transplantation, and overall survival, it is imperative that we measure outcomes that precede these more definitive events. Measuring aspects of care like visit adherence, medication adherence, satisfaction with care, communication outcomes, self-esteem, and self-management skills, will allow providers to identify important associations earlier in care to avoid negative outcomes. Medication adherence and adherence to recommended medical care (preventive care, follow-up visits, etc) appear to be an area of greatest challenge for transitioning patients. Developing standardized methods for measuring adherence and predictors of poor adherence is imperative in devising strategies to improve medical adherence.

Unfortunately there are no standardized or uniformly accepted strategies to measure transitions outcomes. However, because outcomes tend to be poorer after this transition, future efforts should focus on developing evidence-based practices for measuring outcomes in patients who have recently transitioned care. A better understanding of post-transition outcomes and particularly predictors of these outcomes will allow for the development of targeted programs and interventions.