Scratching the Itch: Management of pruritus in cholestatic liver disease

Background

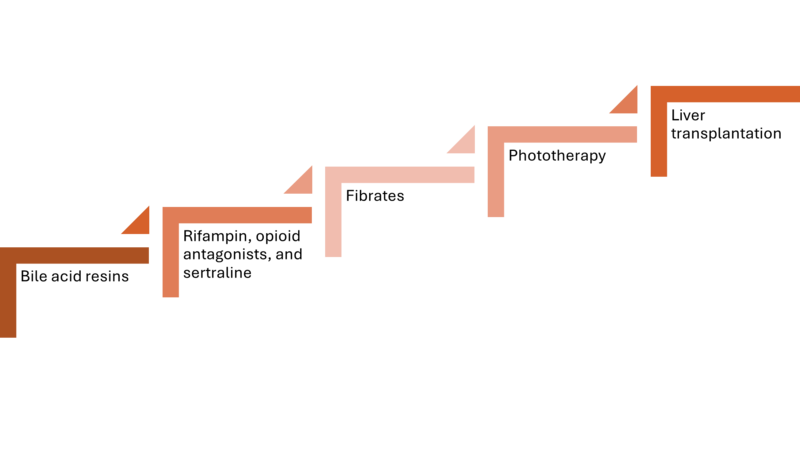

Pruritus is one of the most common symptoms experienced by patients with cholestatic liver disease. Pruritus associated with cholestasis is characteristically localized to the palms and soles, although generalized itching can also occur. Symptoms are often most intense at night, which interferes with sleep and exacerbates fatigue. Despite a significant impact on quality of life, pruritus is undertreated in cholestatic liver disease. In a study of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), a third of patients with clinically significant itch had never received any medical treatment for pruritus. Treatment of pruritus necessitates recognition of this as a symptom of cholestasis, a connection that may not be made by patients. Thus, it is important that providers ask about pruritus in all patients with cholestatic liver disease. While it can be challenging to evaluate pruritus due to its subjective nature, assessment of itch severity can be done through use of a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) or other scoring systems, such as the 5D-Itch Scale and PBC-40 questionnaire. These scoring systems can be particularly helpful when evaluating response to treatments. Several treatment options exist for cholestatic pruritus with varying efficacy, which we will review in this article (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Stepwise approach to cholestatic-pruritus treatment.

Pathogenesis

The pathophysiologic mechanism of pruritus in cholestasis remains poorly understood. It is thought that cholestasis leads to the accumulation of unknown pruritogenic substances that bind to receptors on primary itch neurons (C-fibers) in the skin. This signal gets transmitted across neuronal pathways to the central nervous system, resulting in the sensation of itch. Several potential pruritogens have been proposed, including bile acids, endogenous opioids, and lysophosphatidic acid. However, a definitive culprit has not been identified.

Nonpharmacologic Management

Lifestyle interventions are the first step in management of cholestatic pruritus. These include use of emollients to prevent dry skin, avoiding tight clothing, bathing with tepid (rather than hot) water, using menthol cooling gels for localized pruritus, and keeping fingernails shortened to minimize excoriations. Cognitive behavioral therapy and acupuncture have been effective in treating non-cholestatic causes of pruritus but have not been evaluated in cholestatic-associated pruritus.

Ursodeoxycholic acid

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the mainstay of treatment for PBC and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), but its efficacy in treating the symptom of pruritus is limited. UDCA is not effective for pruritus in PBC or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and the impact on maternal pruritus in ICP is minimal. In rare cases, ursodiol can even exacerbate pruritus. Thus, alternative medications should be considered to treat pruritus in these conditions.

Antihistamines

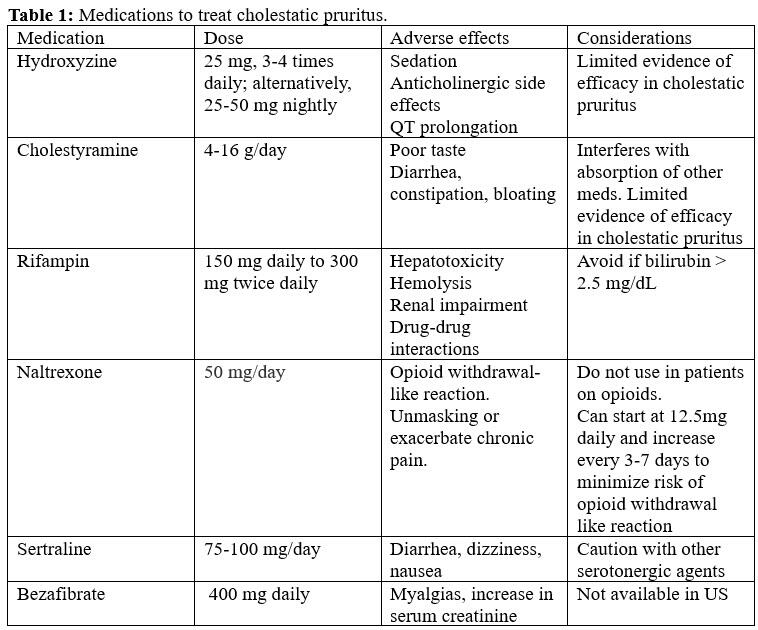

First-generation antihistamines, including diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine, are commonly prescribed for pruritus caused by allergy-related conditions and are often employed early in the treatment of cholestasis-related pruritus (Table 1). However, pruritus in cholestatic liver disease is not histamine-mediated, unlike in atopic conditions, and there is limited evidence to support antihistamine use in cholestatic pruritus. AASLD guidelines for PBC and PSC suggest a role for antihistamine in the treatment algorithm for pruritus, while European guidelines do not recommend antihistamine use in cholestatic liver disease. Sedation is the most notable side effect of first-generation antihistamines, mainly limiting these medications to nighttime dosing. The sedating side effects may be the mechanism behind perceived pruritus relief in cholestatic pruritus, given the nocturnal predominant nature of this symptom.

Bile acid sequestrants

Bile acid sequestrants are considered first-line treatments for cholestatic pruritus, including in PBC and PSC, despite limited evidence of their efficacy. Bile acid sequestrants are positively charged, nonabsorbable resins that bind negatively charged substances like bile acids, which are implicated as pruritogens in cholestatic pruritus. Binding of bile acids prevents their absorption in the terminal ileum, thereby blocking enterohepatic circulation. Cholestyramine powder is the most widely used anion-exchange resin (Table 1). It is dosed at 4-16 g/day and should be taken 20 minutes before meals. Notably, cholestyramine can interfere with the absorption of other medications, so it should be taken 1 hour before or 4 hours after other medications. Its use is further limited by unpalatability and GI side effects including diarrhea, constipation, and bloating. Colestipol and colesevalam are alternative bile acid resins that are available in pill forms, but a randomized controlled trial has shown that colesevalam is ineffective for cholestatic itching.

Sertraline

In two studies comprised mainly of PBC patients, sertraline (optimal dose: 75-100mg/day) improved pruritus independent of its antidepressant effects. While data is limited outside of PBC, sertraline’s minimal side effect profile makes it a practical adjunctive agent for all etiologies of cholestatic pruritus (Table 1). Other antidepressants have been studied in chronic pruritus but do not have evidence to support their use for cholestasis-associated itching.

Rifampin

Rifampin (or rifampicin) is used as a second line treatment of cholestatic pruritus in patients who have not responded to bile acid sequestrants (Table 1). Rifampin, a pregnane X receptor agonist, reduces the expression of a pruritic mediator called autotaxin and also modulates bile acid metabolism through its antimicrobial impact on the gut microbiome. Dosed at 150-300mg twice daily, rifampin’s efficacy has been demonstrated in two meta-analyses. Rifampin carries a risk of hepatotoxicity and should be avoided in patients with a bilirubin ³ 2.5 mg/dL, limiting its use in many cases of cholestatic liver disease. Additional adverse effects include drug interactions, hemolytic anemia, and renal impairment.

Opioid antagonists

Opioid antagonists, including intravenous naloxone and oral naltrexone, have been shown to be effective for cholestasis-related pruritus in multiple studies and a meta-analysis. The effectiveness of opioid antagonists may be due to the finding that patients with cholestatic pruritus have increased levels of endogenous opioids, suggesting a role for endogenous opioids as a pruritogen. The use of opioid antagonists can precipitate a self-limited opioid withdrawal-like reaction, so naltrexone should be introduced at low doses and gradually increased (Table 1). Providers should be aware that long-term use of opioid antagonists can potentially unmask or exacerbate chronic pain.

Fibrates

Fibrates are peroxisome proliferator activator receptor (PPAR) agonists with anti-cholestatic properties. This class of medications has been increasingly studied in treating both the underlying disease process and pruritus of cholestatic liver disease. Bezafibrate, a nonspecific PPAR agonist, improves pruritus in PBC patients with suboptimal response to UDCA. The FITCH trial evaluated the use of bezafibrate for moderate-to-severe pruritus in PSC and PBC patients. The primary outcome (≥50% reduction of pruritus, assessed by VAS) was reached in 45% of patients treated with bezafibrate compared to 11% in the placebo group (p = 0.003). The results of this study led to the European guideline recommendation of bezafibrate as a first-line treatment for pruritus in PSC (Table 1). However, bezafibrate is not currently available in the United States, and the evidence for fenofibrate to treat pruritus is less robust. Adverse effects of fibrates include myalgias, potential hepatotoxicity, and an elevation in creatinine not associated with a decline in glomerular filtration rate.

The role of PPAR agonists in the treatment of cholestatic liver disease will likely continue to grow. Seladelpar, a selective agonist of PPARd, has been shown to reduce liver biochemistries and pruritus among PBC patients in multiple promising phase 3 randomized controlled trials. Conversely, elafibranor, a dual PPAR a and d agonist, did not significantly reduce pruritus compared to placebo in a phase 3 trial.

IBAT inhibitors

Ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT) inhibitors are a newer class of drugs that prevent enterohepatic recirculation of bile acids. Maralixibat and odevixibat have been shown to reduce pruritus in children with Alagille syndrome and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, respectively. Linerixibat showed a signal towards improving pruritus in PBC patients, despite not meeting the primary endpoint in its phase 2b trial. There are multiple ongoing studies of IBAT inhibitors to treat pruritus in PBC, PSC, and biliary atresia. The main side effects of IBAT inhibitors include abdominal pain and diarrhea.

Phototherapy

If conventional therapies fail, a referral to dermatology can be considered for phototherapy. In an observational case series of 13 patients with cholestatic pruritus, ultraviolent B (UVB) phototherapy resulted in a reduction in mean VAS score from 8.0 to 2.0 (p<0.001). Phototherapy is well tolerated.

In cases of intractable pruritus despite standard therapies, liver transplantation may be considered.

Take Home Points

- Patients with cholestatic liver disease should be asked about pruritus.

- Management of cholestatic pruritus involves a stepwise and additive approach (Figure 1).

- Cholestyramine is considered a first-line treatment for cholestatic pruritus.

- Rifampin, naltrexone, and sertraline can be considered in appropriate patients who do not respond to bile acid sequestrants.

- There are several promising drugs in development, including PPAR agonists and IBAT inhibitors, which hope to provide relief of this burdensome symptom.