A Cholestatic Challenge: Identifying Secondary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Secondary Sclerosing cholangitis

Sclerosing cholangitis includes a group of chronic cholestatic liver diseases characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of bile ducts, leading to the formation of strictures. When these strictures are caused by an identifiable condition, it is classified as secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC). Before diagnosing primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), which is idiopathic and immune-mediated, it is essential to rule out all secondary causes.

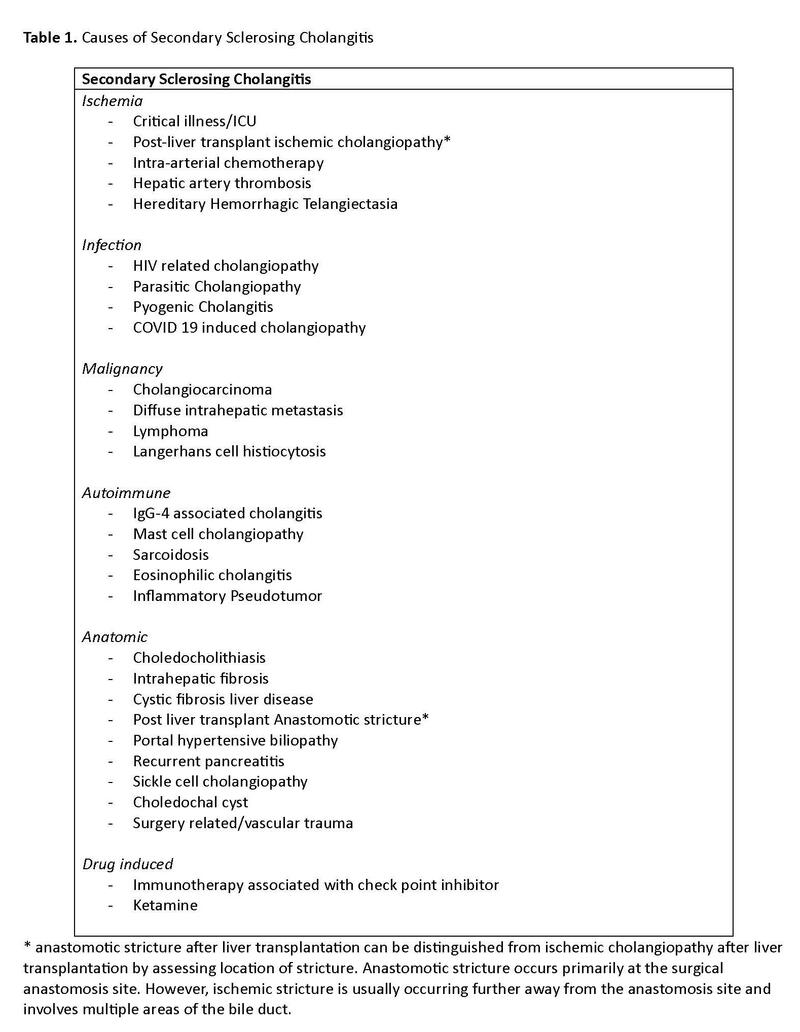

Causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis are listed in Table 1.

SSC is less common than PSC, but its prognosis is generally worse, depending on the underlying cause. Some cases may resolve spontaneously, while others can rapidly progress to cirrhosis and require liver transplantation. In one study, SSC patients had a shorter transplant-free survival compared to PSC patients (72 months vs. 89 months). Unlike PSC, SSC is not associated with an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients (SSC-CIP) is thought to be a type of ischemic cholangiopathy and often progresses rapidly, leading to irreversible biliary cirrhosis. Ischemic SSC can also occur after liver transplant (LT) as a complication and is seen in 2%-19% of cases as a result of hepatic artery thrombosis or stenosis. Another factor that can lead to ischemic SSC is the hepatic arterial infusion of chemotherapy, which can cause significant bile duct damage in 5%-20% of patients, regardless of the specific chemotherapeutic agent used. Sepsis and bacterial infections are well known cause of cholestasis and are collectively termed sepsis induced cholestasis. Unlike SSC-CIP, sepsis-induced cholestasis is generally associated with good prognosis especially if the infection is diagnosed early and treated accordingly.

Risk factors for SSC-CIP

SSC-CIP is a rare but serious condition, occurring in about 1 in 2000 (0.05%) ICU admissions. The condition is more common in men and is associated with various causes of ICU admission, such as severe burns, trauma, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), infections, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and major surgeries. Cardiothoracic surgery, in particular, carries a high risk for SSC-CIP development. The prevalence is notably higher in COVID-19 patients, especially those with ARDS, reaching up to 2.6%, and even higher (23.1%) in patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

The average age at diagnosis for SSC-CIP is 50 years, but cases have been reported across a wide range, from 19 to 79 years. SSC-CIP often develops in patients with prolonged ICU stays, with the average duration being 30–40 days, though it can occur after just 9 days. The condition tends to occur more frequently in men, with reported male-to-female ratios as high as 9:1. The onset of SSC-CIP is often linked to periods of hypotension and reduced blood flow to the liver during mechanical ventilation with high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), prone positioning, and low tidal volumes. Patients typically have severe hemodynamic instability with mean arterial pressure below 65 mmHg for at least 60 minutes.

In the acute stages, ischemia causes the biliary epithelium to desquamate, forming biliary casts that obstruct and dilate the bile ducts. Chronic SSC-CIP is characterized by progressive scarring and fibrosis of the bile ducts, which can ultimately lead to biliary cirrhosis.

Pathophysiology

The liver parenchyma receives blood supply from both the hepatic artery and the portal vein. However, the bile ducts rely solely on arterial blood supply, mainly from the common hepatic artery and its branches, making them particularly susceptible to ischemic injury. The middle third of the common bile duct and the biliary confluence are particularly prone to ischemic injury. The other possible pathophysiologic mechanism proposed is "toxic bile" concept, in which the role of disrupted protective mechanisms for cholangiocytes is believed to be the reason for sclerosing cholangitis. Hydrophobic bile acids, without protection, can damage the lipid membrane of cholangiocytes. In critically ill patients, factors like sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), or hypotension can upset this balance, leading to biliary damage and sclerosing cholangitis.

Clinical Manifestations

- Early Stages: Mostly asymptomatic.

- Progression: As the disease advances, symptoms can include:

- Jaundice

- Pruritus

- Right upper quadrant abdominal pain

Diagnosis

Laboratory assessments in SSC-CIP reveal changes starting with gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), which typically rises 7–9 days after the initial insult, potentially reaching 20–50 times the upper limit of normal (ULN). This is usually followed by an increase in alkaline phosphatase, while bilirubin levels rise last, around 20 days post-insult, peaking at approximately 15 times the ULN. Cholestasis parameters often show an increase within the first days following the acute event. Notably, hypercholesterolemia is present in up to 75% of SSC-CIP patients.

Ultrasound (US) is typically the first diagnostic evaluation, used to rule out gallstones and assess for bile duct dilatation. However, US is normal in most cases as the intrahepatic ducts are primarily involved. The imaging modality of choice is magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which can demonstrate multifocal beading and strictures in the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts. These cholangiographic findings usually develop rapidly and are often irreversible. Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has historically been considered the gold standard for biliary imaging, its potential complications and the non-invasive nature of MRCP make the latter preferable.

Imaging manifestations of SSC-CIP vary by stage. In the initial phase, within the first weeks following injury, imaging may reveal biliary casts, followed by the later appearance of strictures, inflammation, and progressive destruction of the peripheral bile ducts, exacerbating obstructive symptoms. The final stage is characterized by a "pruned-tree" appearance, indicating significant destruction of the intrahepatic bile ducts, leaving only the central biliary system intact, often up to the second bifurcation.

Liver biopsy offers limited diagnostic utility for SSC-CIP because the patterns observed in chronic biliary obstruction are non-specific; it is more useful for ruling out other potential diagnoses.

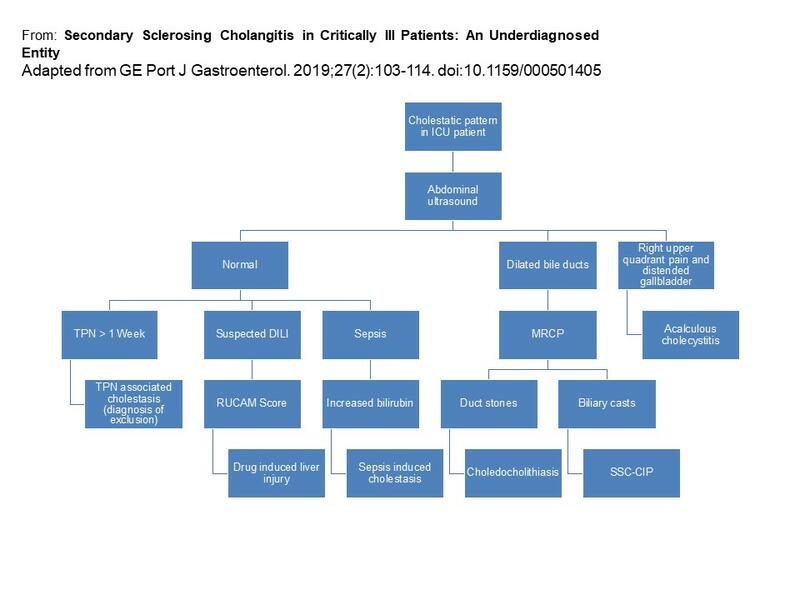

Figure 1. Flow chart for diagnostic consideration

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for cholestasis in the ICU setting is broad and includes conditions such as sepsis-induced cholestasis, total parenteral nutrition, choledocholithiasis, and drug-induced liver injury. A key factor that distinguishes SSC-CIP is the persistence of cholestasis even after clinical recovery.

Figure 2. Differential diagnosis of cholestasis in the ICU (adapted and modified from Martins et al)

Management

SSC-CIP often presents as acute liver failure or rapidly progressive cholestasis leading to cirrhosis in ICU patients. It carries a high risk of complications such as acute acalculous cholecystitis (affecting over 50% within the first year), gallbladder perforation, and liver abscesses. While endoscopic biliary drainage and ursodeoxycholic acid can offer palliative relief, they do not alter the prognosis. Endoscopic removal of biliary casts and sphincterotomy can improve drainage with temporary clinical and laboratory improvement, but recurrence is common.

Liver transplantation (LT) remains the only curative option once biliary cirrhosis has developed, making early referral to an LT center crucial upon diagnosis. About 3/4th of SSC-CIP patients are referred for liver transplantation within the first year of diagnosis. MELD score has been used in European centers and has prognostic value in SSC-CIP. However, it is important to note that similar to PSC, patients with SSC-CIP can develop recurrent bacterial cholangitis which is associated with poor prognosis, despite the normal synthetic function of liver and MELD score. SSC-CIP accounted for 0.61% of all liver transplantations at one hospital, a rate ten times lower than PSC, which represented 6.2% of cases.

Take Home Points

- Secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC) has multiple causes, and a high index of suspicion is essential for timely diagnosis. Lack of awareness may contribute to its under-diagnosis.

- Always rule out secondary causes of sclerosing cholangitis before diagnosing primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

- Persistent cholestatic liver enzyme elevation in ICU patients, especially after recovery from critical illness, should prompt consideration of SSC-CIP.

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the diagnostic modality of choice for SSC-CIP.

- Management of SSC depends on its underlying cause, with SSC-CIP associated with a poor prognosis, often requiring early liver transplant referral.