Why is it recommended to provide reproductive health counseling to women with cirrhosis?

Women with cirrhosis can and do get pregnant! In this post, we will discuss pre-conception counseling for cirrhotic women and how to best manage them throughout their pregnancy.

Why is fertility decreased in liver disease?

Amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea seen in more than 45% of women with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. Fertility is estimated to be 40% lower in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. This is thought to be due to alterations in estrogen metabolism and changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. One study found lower serum luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone in women with cirrhosis as compared to controls, which is hypothesized to lead to anovulation and decreased fertility in this setting.

Changes in estrogen metabolism are also hypothesized to affect the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Cirrhotic livers are thought to have impaired capacity to metabolize and inactivate estrogens resulting in increased circulating estrogen, which is potentially exacerbated by portosystemic shunting. Malnutrition associated with liver disease can also contribute to decreased fertility.

Although fertility is impaired, it is still possible, and it is currently estimated that 1 per 3,000-6,000 pregnancies are individuals with cirrhosis. This is estimated to be a 7-fold increase over the past 20 years, mostly due to increased number of pregnancies in patients with compensated cirrhosis. The increase in the total number of pregnancies in patients with liver disease may partially be attributable to changes in the epidemiology of liver disease. For example, there are more young women living with liver disease given overall higher prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and alcohol-related liver disease in this population.

In vitro fertilization has been found to be a potential option for women with cirrhosis wishing to conceive. In one retrospective study of women with liver disease undergoing IVF, 3 out of 6 patients with cirrhosis went on to have successful live births. A quarter of patients with cirrhosis had unsuccessful IVF attempts. One patient with autoimmune-related cirrhosis decompensated after initiating IVF, warranting discontinuation of therapy. However, the study only looked at a small number of patients and further studies are needed to help determine what patients can safely benefit from IVF.

Why are there increased risks of hepatic decompensations during pregnancy?

There has also been a shift over time in the way the medical community approaches pregnancy in cirrhotic women. In the past, pregnancy used to be considered absolutely contraindicated due to reportedly high mortality rates of up to 20%.in part due to hepatic decompensations during pregnancy. Newer figures estimate maternal mortality somewhere less than 2% and it is no longer contraindicated.

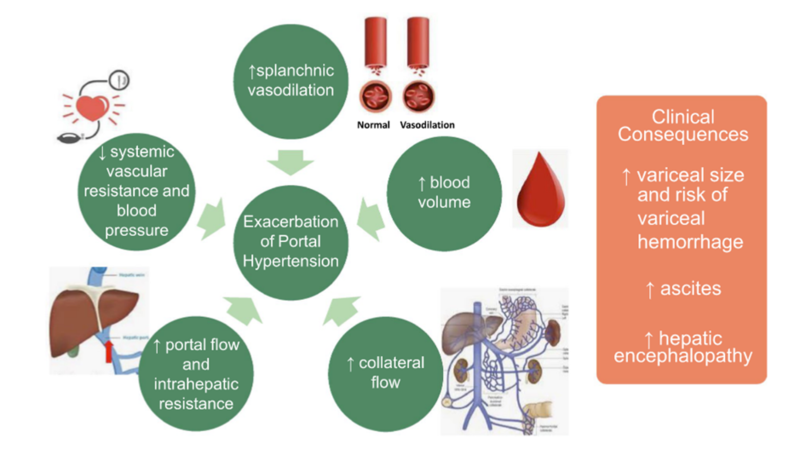

There are tremendous changes in physiology that occur during pregnancy that increase the risk of hepatic decompensations. Pregnancy is associated with increased circulating plasma volume, heart rate, and cardiac output as well as decreased systemic and splanchnic vascular resistance. Blood volume increases by 30 to 50% throughout pregnancy and cardiac output can increase by up to 45% by the third trimester. Additionally, the gravid uterus can put additional pressure on the inferior vena cava potentially causing compression and increased portal pressures.

These changes can exacerbate portal hypertension potentially resulting in variceal bleeding and ascites. Severity of liver disease pre-conception is associated with the risk of hepatic decompensations during pregnancy.

What clinical factors predict worse pregnancy outcomes in patients with liver disease?

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) is a helpful prognostic tool currently available to risk stratify pregnant patients. In one study, MELD ≥10 was found to have 83% sensitivity and 83% specificity for predicting hepatic decompensation such as variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy during the pregnancy. Half of the women that had a screening endoscopy during the second trimester were found to have esophageal varices however pre-conception MELD was not significantly associated with the presence of varices at the time of exam. The study did not look at whether patients were receiving variceal prophylaxis with beta-blockers at the time of their variceal bleed. No individuals with MELD score less than or equal to 6 at the beginning of pregnancy developed any hepatic decompensations.

It is generally recommended that all women with cirrhosis and in particular those with MELD score greater than 10, should be counseled about the risk of worsening liver disease during pregnancy. However, the absolute risk is still probably small. A North American cohort study found that only 1.6% of pregnant women with cirrhosis developed a decompensation during their pregnancy, the majority of which were variceal bleeds. The authors put together this fantastic figure about the epidemiology of pregnancy trends and outcomes in their cohort:

There are also increased risks to the fetus that women considering pregnancy should think about. In one Swedish study, women with cirrhosis had increased risk of severe maternal and fetal outcomes compared to non-cirrhotics such as low birth weight (15% vs. 3%), preterm delivery (19% vs. 5%), and neonatal death (1% vs. 0.2%). Although there was a significant difference in adverse events, the absolute number of events were rare and the majority of women in the study population had successful pregnancies without any complications.

What monitoring for hepatic decompensations should be done during pregnancy?

Varices

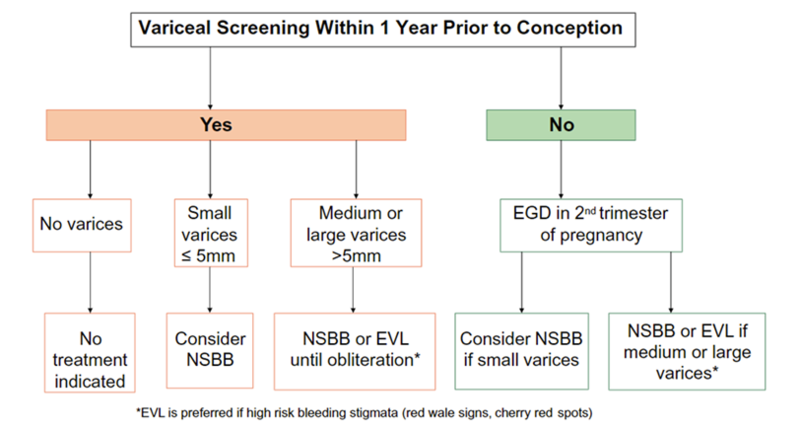

Due to increased risk of variceal bleeding during pregnancy, variceal screening is recommended for all women with cirrhosis or non-cirrhotic portal hypertension within 12 months of conception. It can be difficult to predict when someone might become pregnant, so it is important to ask patients about family planning so that future pregnancies can be anticipated. If variceal screening isn’t done prior to pregnancy, it is safe to do an upper endoscopy in the 2nd trimester.

Platelets less than 110 may be able to predict the presence varices during pregnancy with reasonable sensitivity. However, non-invasive tests such as FIB-4 can miss up to a quarter of small varices, which is problematic given that small varices should be treated given their risk of enlarging during pregnancy. Therefore, AASLD guidance recommends against using non-invasive tests to screen for varices and upper endoscopy is the test of choice to evaluate for varices (see figure below).

If any varices are present, they should be treated with a non-selective beta-blocker or undergo banding. Propranolol is the preferred non-selective beta-blocker in pregnancy due its shorter half-life and higher protein-binding than nadolol. Older studies demonstrated an association between beta-blockers and potential fetal cardiac anomalies, although this has recently been debunked. There is less data on the use of carvedilol during pregnancy, although there have been no reported adverse maternal or fetal outcomes in humans.

If variceal bleeding occurs during pregnancy, treatment is the same as for non-pregnant patients. The one caveat is that terlipressin should be avoided due to the potential for reduction in uterine blood flow. Otherwise, proton pump inhibitors, octreotide and cephalosporins antibiotics are all considered safe in pregnancy.

Ascites and Hepatic Encephalopathy

Ascites and hepatic encephalopathy are less commonly seen hepatic decompensations during pregnancy but are important to evaluate patients for throughout pregnancy. Management of these decompensations should be largely similar to non-pregnant individuals. Ascites can be managed with safely with Lasix, which is a category C drug. Amiloride is another diuretic option and is pregnancy category B. Spironolactone is category C but has been found to have antiandrogenic effects in animal studies and should be used with caution in women carrying male fetuses. Paracentesis can also be safely performed but requires special attention to the placement of the paracentesis needle to avoid trauma to the uterus. In a small study of 5 patients, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) was able to successfully be placed during pregnancy and all patients went onto successfully deliver and can be considered in select patients.

Hepatic encephalopathy can be treated in pregnancy patients with lactulose, which is a class B medication and can also assist with pregnancy-related constipation, which can affect up to 40% of all pregnant women. Rifaximin is a class C and although data is lacking, has evidence of teratogenicity in animal models. Certain medications such as anesthesia or narcotics that might be delivered at the time of delivery have the potential to precipitate or worsen hepatic encephalopathy so should be minimized if possible.

What special populations require additional monitoring during pregnancy?

Autoimmune Hepatitis

It is recommended that patients with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) delay conception until their liver disease is well controlled on stable doses of immunosuppressants for at least 1 year. Mycophenolic acid, which is commonly used in patients with autoimmune hepatitis, is a known teratogen and is associated with high risk of miscarriage and birth defects. Women on mycophenolic acid containing products should be switched to another immunosuppressant if they are considering pregnancy. Azathioprine is a safe alternative. In a large meta-analysis, liver enzymes were lowest during pregnancy and loss of biochemical remission occurred most frequently in the first several months after delivery and is estimated to occur in up to a quarter of patients . Patients with pre-conception portal hypertension had 9 time the risk of preterm delivery as compared to non-cirrhotic patients with AIH. All patients with AIH had more than double the risk of preterm delivery compared to those without AIH.

Hepatitis B

All women should be screening for hepatitis B and C during their pregnancy. There is an increased risk of maternal to fetal transmission in patients positive for hepatitis B surface antigen. All infants born to hepatitis B positive mothers should be vaccinated against hepatitis B and receive hepatitis B immunoglobulin within the first several hours of delivery. However, transmission can still occur and is more likely with increasing maternal viral load. Therefore, it is recommended that everyone positive for hepatitis B should have HBV DNA drawn in the second trimester and if maternal HBV DNA is greater than 200,000 IU/mL, antiviral therapy should be started between gestational weeks 28 and 32 to allow adequate time to reduce the viral load. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) is the preferred treatment and has been found to be safe and effective in systematic reviews.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C maternal to fetal transmission is estimated to be less than 6% and is currently not recommended to be treated during pregnancy. Data from small safety studies of patients treated with direct-acting antivirals have not shown increased risk of complications and although more research is needed before treatment during pregnancy can be recommended. C-sections have not been found to reduce the risk of hepatitis C transmission and should only be recommended for obstetrical indications.

Chronic Cholestatic Liver Diseases

Most women with PBC have stable disease throughout pregnancy, but up to 70% have biochemical flares in the postpartum period. Itching is a common symptom and can develop in up to half of all PBC patients. Ursodeoxycholic acid is safe in pregnancy and has not been shown to be associated with any adverse effects in pregnancy or breastfeeding. Obeticholic acid and fibrate lack safety data to recommend their use at this time.

Alcohol-associated Liver Disease

Given the risks associated with alcohol use during pregnancy, which include low birth weight, preterm birth, and potentially fetal alcohol syndrome, patients with alcohol-related liver disease are recommended to achieve alcohol abstinence prior to conception. Medications used to assist with alcohol abstinence are not well studied in the setting of pregnancy, although naltrexone appears to be safe.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

NAFLD is the leading cause for liver disease in pregnant patients. A study from Sweden found more than twice the risk of preterm births and small for gestational age births in NAFLD compared with non‐NAFLD, even after adjustment for BMI and gestational diabetes. A large U.S base cohort study similarly found higher rates of preterm births (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3‐2.0) and hypertensive complications (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 2.6‐3.8) in women with NAFLD compared to those without liver disease. Lifestyle modifications are recommended pre-conception and during pregnancy to target an optimal weight and management of medical comorbidities. There is limited human data regarding newer weight loss medications such as GLP-1 agonists during pregnancy and they are currently not recommended during pregnancy. Breastfeeding is encouraged in women with NAFLD due to the association with lower rates of NALFD in adult offspring and restoration of maternal metabolism after pregnancy. There is also data that prolonged breastfeeding greater than 6 months was protective against NAFLD in middle age even after adjusting for confounders and this benefit may extend to women with already established NAFLD although more research is needed.

Budd-Chiari

Pregnancy tips the hemostatic balance towards hypercoagulability that lasts throughout pregnancy and up to 2 months postpartum. The risk of venous thromboembolism is estimated to be up to 6 times higher during pregnancy compared to the general female population and is a risk factor for Budd-Chiari in the presence of underlying clotting disorders. If anticoagulation is needed, heparin and low molecular weight heparin are the only anticoagulants that are currently acceptable in pregnancy. Patients with Budd-Chiari preconception have been found to successfully carry pregnancies to term in a majority of cases and should not be a contraindication to pregnancy.

What are the best birth control options for women with cirrhosis?

Contraception counseling is important for those who want to avoid pregnancy or who require additional planning to minimize pregnancy‐associated risks. Estrogen containing oral contraception is considered safe in women with compensated cirrhosis but should be avoided in decompensated cirrhosis due to concerns of impaired estrogen metabolism. Estrogen can cause intraheptic cholestasis which can worsen liver disease. Cholestasis due to estrogens and OCPs appears to be related to inhibition of bilirubin and bile acid secretion related to effects of estrogens on the orphan nuclear receptors that modulate bile acid and bilirubin metabolism. It is also associated with venous thrombosis and should be avoided with history of Budd Chiari. Lastly , it can promote liver tumor growth in the case of hepatic adenomas and should be avoided.

Progestin only contraception appears to be safer. Long-acting contraception with intrauterine devices (IUDs) have low failure rates of less than 1% and are generally preferred. Copper IUDs are effective for at least 10 years and hormonal IUDs that contain progestin can be used for up to 5 years. Contraception with low failure rate is particularly important if a patient is on teratogenic medication such as mycophenolate.

Progestin only contraception appears to be safer. Long-acting contraception with intrauterine devices (IUDs) have low failure rates of less than 1% and are generally preferred. Copper IUDs are effective for at least 10 years and hormonal IUDs that contain progestin can be used for up to 5 years. Contraception with low failure rate is particularly important if a patient is on teratogenic medication such as mycophenolate.

Reproductive health counseling is critical in women of childbearing age to ensure the use of safe and effective contraception in those wishing to avoid pregnancy and allow for planning to decrease pregnancy related risks. There are many women with cirrhosis who have had successful pregnancies through careful planning and monitoring by their providers. Ongoing attention will help ensure healthy outcomes for mothers with liver disease and their babies in the future.