How to approach elevated liver enzymes?

Learning Objectives

In this Back-to-Basics series, the learner will be able to:

1. Recognize the significance of liver enzymes and markers of liver function.

2. Develop differential diagnoses by identifying patterns in abnormal liver function enzymes.

3. Distinguish initial diagnostic evaluation based on liver injury patterns.

What are liver enzymes?

As covered in a previous Back to Basics post, liver enzymes can be categorized into markers of liver injury (alanine and aspartate aminotransferases (ALT and AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and gamma glutamyl-transferase (GGT), and markers of liver function including albumin, clotting factors (prothrombin time/INR, fibrinogen), and bilirubin.

Fast facts on liver enzymes:

1) Aminotransferases are the most sensitive markers of acute hepatocellular injury. ALT is more specific to liver injury because of its greatest concentration in the liver, while AST can also be found in extrahepatic organs, including brain, heart, and skeletal muscle. The degree of aminotransferase elevation in serum does not correlate with extent of liver injury.

2) Alkaline phosphatase are enzymes found on the canalicular membrane of hepatocytes. About 80% of ALP is found in liver cells and bone, with smaller amounts in the placenta, ileal mucosa, and kidneys. Due to increased enzyme synthesis, ALP levels can rise with hepatocellular injury or cholestasis. Bone disease can also elevate ALP; in these cases, GGT—typically elevated in hepatobiliary disease—can help confirm liver as the source.

3) Albumin, the most abundant protein in plasma, makes up about half of its total protein content and is synthesized exclusively by hepatocytes. A decrease in albumin typically indicates liver disease lasting at least two to three weeks (reflecting albumin’s half-life). However, it can also decrease in inflammation, nephrotic syndrome, fluid overload, or malnutrition therefore this is also a non-specific marker of liver function.

4) Clotting factors such as Prothrombin time (PT) reflect the extrinsic coagulation pathway. Since the liver synthesizes multiple clotting factors (with exception of factor VIII), PT elevation can indicate deficiencies tied to severe hepatic dysfunction and may be affected within 24 hours of liver disease onset. PT can also be prolonged due to vitamin K deficiency, certain anticoagulants, or disseminated intravascular coagulation. Importantly, PT is not a reliable indicator of bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis.

5) Bilirubin exists in two forms: unconjugated and conjugated. Unconjugated bilirubin, bound to albumin in the plasma, primarily results from the breakdown of hemoglobin in senescent blood cells. It is transported to the liver, where it undergoes conjugation before being excreted into the bowel and eliminated in feces. While not a direct marker of liver function, bilirubin metabolism is closely tied to the liver’s ability to conjugate and excrete substances.Therefore, direct bilirubinemia can be more telling for liver function over indirect bilirubinemia which can result from other extrahepatic issues such as hemolysis.

What are patterns of abnormal liver enzymes?

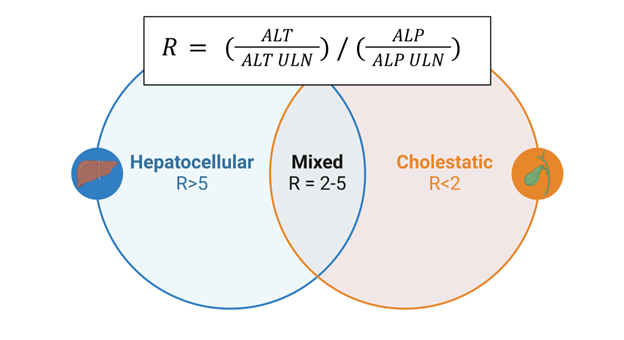

The R-value is a scoring tool to identify liver injury patterns by comparing aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels to their upper normal limits (R = (ALT ÷ ULN ALT) / (ALP ÷ ULN ALP)). Based on the R-value, liver injury patterns can be classified as hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed. Please note that bilirubin is not included in this particular tool.

Figure 1. R-value and the different patterns of liver injury.

Figure re-drawn from BioRender

1) Hepatocellular pattern: The degree of AST and ALT elevation varies based on the underlying cause of hepatocellular injury. Additionally, the AST/ALT ratio provides diagnostic clues; in alcohol associated liver disease, around 90% of patients have an AST/ALT ratio >2, likely due to alcohol-related depletion of pyridoxal phosphate, needed for ALT synthesis, and release of mitochondrial AST due to alcohol-mediated damage. Elevated AST > ALT can also appear in cirrhosis from any cause, though the ratio is less pronounced than in alcohol associated liver disease.

2) Cholestatic pattern: Typically indicates biliary duct pathology, often requiring additional testing or imaging to determine the underlying cause. Cholestatic liver diseases are further classified into intrahepatic and extrahepatic causes.

3) Mixed pattern: Has characteristics of both cholestatic and hepatocellular pattern of injury. Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) can present as any pattern of injury including a mixed pattern depending on the offending agent. Certain types of liver insults can start off as more hepatocellular and become mixed over time as synthetic function becomes impaired and a patient becomes jaundiced from hyperbilirubinemia.

| Hepatocellular | Cholestatic | Mixed |

| Drugs/Toxins | Drugs/Toxins | Drugs/Toxins |

| Alcohol-associated hepatitis | Primary Biliary Cholangitis | Alcohol-associated hepatitis |

| Alcohol-associated liver disease | Alcohol-associated liver disease | Alcohol-associated liver disease |

| MASLD/MASH | Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis | MASLD/MASH |

| Viral Hepatitis | Viral Hepatitis | Viral Hepatitis |

| Autoimmune Hepatitis | Malignancy | |

| Ischemic Hepatitis | Choledocholithiasis | |

| Shock Liver | Biliary Strictures | |

| Hemochromatosis | Sepsis | |

| Wilson’s Disease | Total parenteral nutrition |

Table 1. Differential Diagnoses for patterns of liver injury

What is a framework to approach elevated liver enzymes?

Start your assessment with a thorough history and physical exam, focusing on any underlying liver disease, alcohol use, medications, herbal supplements, risk factors for viral hepatitis or metabolic disease, and relevant comorbidities that might suggest a specific cause. Examine for signs of chronic liver disease, which can include jaundice, pruritus, edema, palmar erythema, caput medusae, asterixis, and other findings on physical exam.

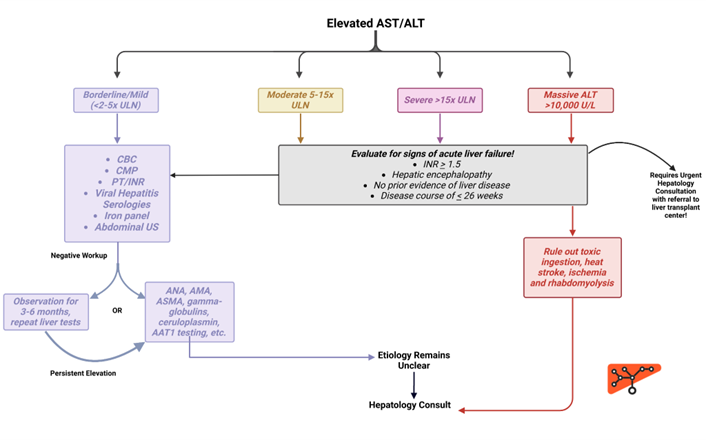

The degree of AST/ALT elevation can guide management. Your initial workup should include CBC, AST/ALT, ALP, bilirubin, PT/INR, a hepatitis panel, iron studies, and an abdominal ultrasound. For borderline and mild elevations, this is generally sufficient. Moderate elevations often share causes with milder cases but may warrant testing for autoimmune conditions. Testing for toxins and ischemic or thrombotic causes should be considered for severe and massive elevations. Liver biopsy may be needed for unclear etiologies or to confirm autoimmune etiology. A consultation with a hepatologist is highly recommended in this situation. Always consider acute liver failure in patients with acute liver injury, no prior history of liver disease, who present with encephalopathy. Transfer to a liver transplant center is a priority for patients with acute liver failure.

Transient elastography (Fibroscan) can help risk stratify liver disease by measuring liver stiffness and estimate the degree of steatosis. Availability of transient elastography can be however limited. For details on non-invasive testing strategies, please review this Back to Basics post.

Here is a proposed stepwise approach to a patient presenting with elevated aminotransferases. This is stratified by the degree of aminotransferase elevation.

Figure 2. Stepwise approach to elevated aminotransferases

Figure re-drawn from BioRender

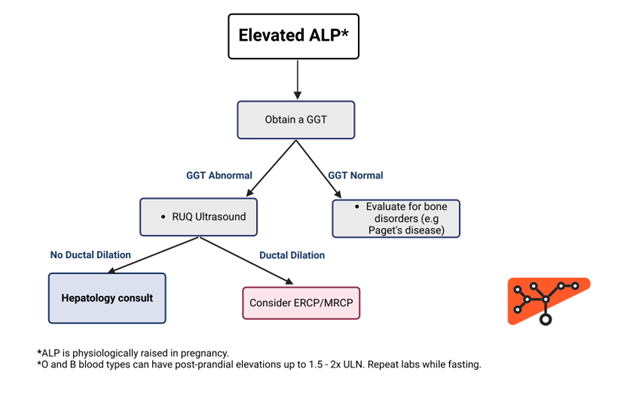

Cholestatic liver disease often presents with elevated ALP, with or without bilirubin elevation. Isolated ALP elevation warrants GGT testing to confirm the source. An abdominal ultrasound can help differentiate between extrahepatic and intrahepatic cholestatic disease by assessing for biliary duct dilation. Extrahepatic causes may require further imaging with MRCP or ERCP, while suspected intrahepatic causes warrant additional serology to evaluate for autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary biliary cholangitis.

Figure 3. Stepwise approach to elevated alkaline phosphatase

Figure re-drawn from BioRender

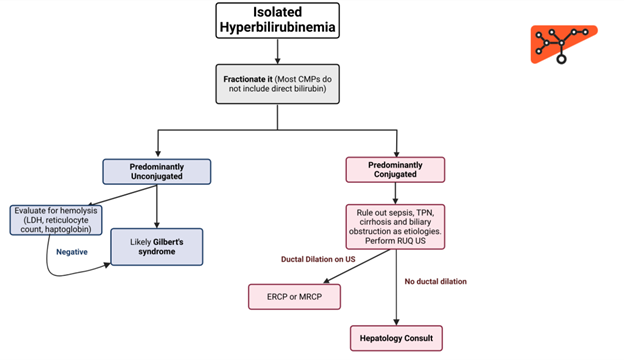

For isolated bilirubin elevations, start by fractionating the total bilirubin into conjugated and unconjugated levels. Purely unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia typically suggests overproduction (e.g., hemolysis), reduced hepatic uptake, or impaired conjugation. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia usually points to parenchymal liver damage or obstruction, as seen in conditions like sepsis, cirrhosis, or alcohol-associated hepatitis, though biliary ductal pathologies should also be considered.

Figure 4. Stepwise approach to isolated hyperbilirubinemia

Figure re-drawn from BioRender

Take-home points:

- Liver chemistries include markers of injury (e.g., AST, ALT, ALP) and synthesis (e.g., albumin, PT, bilirubin). Predominant AST/ALT elevations suggest hepatocellular injury, primarily elevated bilirubin/ALP indicates cholestatic injury and mixed patterns include elevations of enzymes without a certain predominance.

- The R-value can help you categorize liver injury into hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed patterns.

- The diagnostic workup for abnormal liver enzymes usually starts with additional serologic testing and imaging. Further evaluation (advanced imaging techniques, fibrosis assessment, liver biopsy) is considered depending on the patient’s trajectory (unresolved injury, diagnosis in question, need for disease staging) and should prompt hepatology referral.